However picturesquely Fremont for the moment loomed up as the standard-bearer of the Republican party, historical interest centers upon the second act of the Philadelphia Convention.

Continuing Republicans’ First National Campaign,

our selection from Abraham Lincoln, A History by John Hay and John G. Nicolay published in 1890. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages The selection is presented in three easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Republicans’ First National Campaign.

Time: 1856

Place: Philadelphia

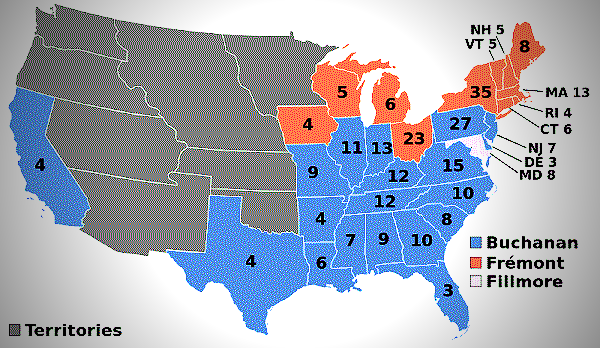

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

That [political – jl] conflict which opened the year with the long congressional contest over the speakership, and which found its only solution in the choice of Banks by a plurality vote, had been fed by fierce congressional debates, by presidential messages and proclamations, by national conventions, by the Sumner assault, by the Kansas war; the body politic throbbed with activity and excitement in every fiber. Every free-State and several border States and Territories were represented in the Philadelphia Convention; its regular and irregular delegates counted nearly a thousand local leaders, full of the zeal of new proselytes; Henry S. Lane, of Indiana, was made its permanent chairman.

The party was too young and its prospect of immediate success too slender to develop any serious rivalry for a presidential nomination. Because its strength lay evidently among the former adherents of the now dissolved and abandoned Whig party, William H. Seward of course took highest rank in leadership; after him stood Salmon P. Chase as the representative of the independent Democrats, who, bringing fewer voters, had nevertheless contributed the main share of the courageous pioneer work. It is a just tribute to their sagacity that both were willing to wait for the maturer strength and riper opportunities of the new organization. Justice John McLean, of the Supreme Bench, an eminent jurist, a faithful Whig, whose character happily combined both the energy and the conservatism of the great West, also had a large following; but as might have been expected, the convention found a more typical leader, young in years, daring in character, brilliant in exploit; and after one informal ballot it nominated John C. Fremont, of California. The credit of the selection and its successful management has been popularly awarded to Francis P. Blair, senior, famous as the talented and powerful newspaper lieutenant of President Jackson; but it was rather an intuitive popular choice, which at the moment seemed so appropriate as to preclude necessity for artful intrigue.

There was a dash of romance in the personal history of Fremont which gave his nomination a high popular relish. Of French descent, born in Savannah, Georgia, orphaned at an early age, he acquired a scientific education largely by his own unaided efforts in private study; a sea voyage as teacher of mathematics, and employment in a railroad survey through the wilderness of the Tennessee Mountains, developed the taste and the qualifications that made him useful as an assistant in Nicollet’s scientific exploration of the great plateau where the Mississippi River finds its sources, and secured his appointment as second lieutenant of topographical engineers. These labors brought him to Washington, where the same Gallic restlessness which made the restraint of schools insupportable, brought about an attachment, elopement, and marriage with the daughter of Senator Thomas H. Benton, of Missouri.

Reconciliation followed in good time; and the unexplored Great West being Benton’s peculiar hobby, through his influence Fremont was sent with an exploring party to the Rocky Mountains. Under his command similar expeditions were repeated again and again to that mysterious wonderland; and never were the wildest fictions read with more avidity than his official reports of daily adventure, danger and discovery, of scaling unclimbed mountains, wrecking his canoes on the rapids of unvisited rivers, parleying and battling with hostile Indians, and facing starvation while hemmed in by trackless snows. One of these journeys had led him to the Pacific coast when our war with Mexico let loose the spirit of revolution in the Mexican province of California. With his characteristic restless audacity Fremont joined his little company of explorers to a local insurrectionary faction of American settlers, and raised a battalion of mounted volunteers. Though acting without Government orders, he cooperated with the United States naval forces sent to take possession of the California coast, and materially assisted in overturning the Mexican authority and putting the remnant of her military officials to flight. At the close of the conquest he was for a short time military governor; and when, through the famous gold discoveries, California was organized as a State and admitted to the Union, Fremont became for a brief period one of her first United States Senators.

So salient a record could not well be without strong contrasts, and of these unsparing criticism took advantage. Hostile journals delineated Fremont as a shallow, vainglorious, “woolly-horse,” “mule-eating,” “free-love,” “nigger-embracing” black Republican; an extravagant, insubordinate, reckless adventurer; a financial spendthrift and political mountebank. As the reading public is not always skillful in winnowing truth from libel when artfully mixed in print, even the grossest calumnies were not without their effect in contributing to his defeat. But to the sanguine zeal of the new Republican party, the “Pathfinder” was a heroic and ideal leader; for, upon the vital point at issue, his anti-slavery votes and clear declarations satisfied every doubt and inspired unlimited confidence.

However picturesquely Fremont for the moment loomed up as the standard-bearer of the Republican party, historical interest centers upon the second act of the Philadelphia Convention. It shows us how strangely to human wisdom vibrate the delicately balanced scales of fate; or rather how inscrutable and yet how unerring are the far-reaching processes of divine providence. The principal candidate having been selected without contention or delay, the convention proceeded to a nomination for Vice-President. On the first informal ballot William L. Dayton, of New Jersey, received 259 votes and Abraham Lincoln, of Illinois, 110; the remaining votes being scattered among thirteen other names. The dominating thought of the convention being the assertion of principle, and not the promotion of men, there was no further contest; and though Mr. Dayton had not received a majority support, his nomination was nevertheless at once made unanimous. Those who are familiar with the eccentricities of nominating conventions when in this listless and drifting mood know how easily an opportune speech from some eloquent delegate or a few adroitly arranged delegation caucuses might have reversed this result; and imagination may not easily construct the possible changes in history which a successful campaign of the ticket in that form might have wrought. What would have been the consequences to America and humanity had the Rebellion, even then being vaguely devised by Southern Hotspurs, burst upon the nation in the winter of 1856, with the nation’s sword of commander-in-chief in the hand of the impulsive Fremont, and Lincoln, inheriting the patient wariness and cool blood of three generations of pioneers and Indian-fighters, wielding only the powerless gavel of Vice-President? But the hour of destiny had not yet struck.

The platform devised by the Philadelphia Convention was unusually bold in its affirmations, and most happy in its phraseology. Not only did it “deny the authority of Congress, or of a territorial legislature, of any individual or association of individuals, to give legal existence to slavery in any Territory of the United States”; it further “Resolved, That the Constitution confers upon Congress sovereign power over the Territories of the United States for their government, and that in the exercise of this power it is both the right and the duty of Congress to prohibit in the Territories those twin relics of barbarism — polygamy and slavery.”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.