Today’s installment concludes Republicans’ First National Campaign,

our selection from Abraham Lincoln, A History by John Hay and John G. Nicolay published in 1890. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of three thousand words. Congratulations!

Previously in Republicans’ First National Campaign.

Time: 1856

Place: USA

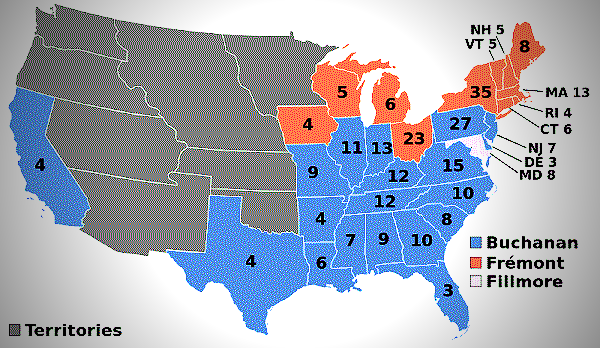

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

At Buchanan, recently nominated by the Democratic National Convention in Cincinnati, it [the Republican platform – jl] aimed a barbed shaft:

Resolved, That the highwayman’s plea that ‘might makes right,’ embodied in the Ostend circular, was in every respect unworthy of American diplomacy, and would bring shame and dishonor upon any government or people that gave it their sanction.” It demanded the maintenance of the principles of the Declaration of Independence, of the Federal Constitution, of the rights of the States, and the union of the States. It favored a Pacific railroad, congressional appropriations for national rivers and harbors; it affirmed liberty of conscience and equality of rights; it arraigned the policy of the Administration; demanded the immediate admission of Kansas as a State, and invited “the affiliation and cooperation of men of all parties, however differing from them in other respects, in support of the principles declared.”

The nominees and platform of the Philadelphia Convention were accepted by the opposition voters of the free-States with an alacrity and an enthusiasm beyond the calculation of even the most sanguine; and in November a vote was recorded in their support which, though then unsuccessful, laid the secure foundation of an early victory, and permanently established a great party destined to carry the country through trials and vicissitudes equal in magnitude and results to any which the world had hitherto witnessed.

In that year none of the presidential honors were reserved for the State of Illinois. While Lincoln thus narrowly missed a nomination for the second place on the Republican ticket, his fellow-citizen and competitor, Douglas, failed equally to obtain the nomination he so much coveted as the candidate of the Democratic party. The Democratic National Convention had met at Cincinnati on the 2d day of June, 1856. If Douglas flattered himself that such eminent services as he had rendered the South would find this reward, his disappointment must have been severe. While the benefits he had conferred were lightly estimated or totally forgotten, former injuries inflicted in his name were keenly remembered and resented. But three prominent candidates, Buchanan, Pierce, and Douglas, were urged upon the convention. The indiscreet crusade of Douglas’s friends against “old fogies” in 1852 had defeated Buchanan and nominated Pierce; now, by the turn of political fortune, Buchanan’s friends were able to wipe out the double score by defeating both Pierce and Douglas. Most of the Southern delegates seem to have been guided by the mere thought of present utility; they voted to renominate Pierce because of his subservient Kansas policy, forgetting that Douglas had not only begun it, but was their strongest ally to continue it. When after a day of fruitless balloting they changed their votes to Douglas, Buchanan, the so-called “old fogy,” just returned from the English mission, and therefore not handicapped by personal jealousies and heart-burnings, had secured the firm adhesion of a decided majority mainly from the North.

The “two-thirds rule” was not yet fulfilled, but at this juncture the friends of Pierce and Douglas yielded to the inevitable, and withdrew their favorites in the interest of “harmony.” On the seventeenth ballot, therefore, and the fifth day of the convention, James Buchanan, of Pennsylvania, became the unanimous nominee of the Democratic party for President, and John C. Breckinridge, of Kentucky, for Vice-President.

The famous “Cincinnati platform” holds a conspicuous place in party literature for length, for vigor of language, for variety of topics, for boldness of declaration; and yet, strange to say, its chief merit and utility lay in the skillful concealment of its central thought and purpose. About one-fourth of its great length is devoted to what to the eye looks like a somewhat elaborate exposition of the doctrines of the party on the slavery question. Eliminate the verbiage and there only remains an endorsement of the “principles contained in the organic laws establishing the Territory of Kansas and Nebraska” (non-interference by Congress with slavery in State and Territory, or in the District of Columbia); and the practical application of “the principles” is thus further defined: “Resolved, That we recognize the right of the people of all the Territories, including Kansas and Nebraska, acting through the legally and fairly expressed will of a majority of actual residents, and whenever the number of their inhabitants justifies it, to form a constitution with or without domestic slavery, and be admitted into the Union upon terms of perfect equality with the other States.”

We have already seen how deliberately the spirit and letter of “the principle” was violated by the Democratic National Administration of President Pierce, and by nearly all the Democratic Senators and Representatives in Congress; and we shall see how the more explicit resolution was again even more flagrantly violated by the Democratic National Administration and party under President Buchanan.

For the time, however, these well-rounded phrases were especially convenient: first, to prevent any schism in the Cincinnati Convention itself, and, secondly, to furnish points for campaign speeches; politicians not having any pressing desire, nor voters the requisite critical skill, to demonstrate how they left untouched the whole brood of pertinent queries which the discussion had already raised, and which at its next national convention were destined to disrupt and defeat the Democratic party. For this occasion the studied ambiguity of the Cincinnati platform made possible a last coC6peration of North and South, in the face of carefully concealed mental reservations, to secure a presidential victory.

It is not the province of this work to describe the incidents of the national canvass, but only to record its results. At the election of November, 1856, Buchanan was chosen President. The popular vote in the nation at large stood: Buchanan, 1,838,169; Fremont, 1,341,264; Fillmore, 874,534. By States Buchanan received the votes of fourteen slave-States and five free-States, a total of 174 electors; Fremont the vote of eleven free-States, a total of 114 electors; and Fillmore the vote of one slave-State, a total of eight electors.

In the campaign which preceded Mr. Buchanan’s election, Mr. Lincoln, at the head of the Fremont electoral ticket for Illinois, took a prominent part, traversing the State in every direction, and making about fifty speeches.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Republicans’ First National Campaign by John Hay and John G. Nicolay from his book Abraham Lincoln, A History published in 1890. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.