This series has four easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: English Accuses Jews.

Introduction

Richard I had special dealings with the Jews, the effectual results of which were more securely to bind them as crown chattels and to add to the royal emoluments. King John, well estimating the importance of the Jews as a source of revenue, began his reign by heaping favors upon them, which only made his subjects in general look upon them with more jealousy. Under Henry III both the wealth of the Jews and the oppressions which laid exactions upon it increased; and during the half-century preceding their expulsion from the realm, their condition, as shown by Milman, became more and more intolerable.

This selection is from History of the Jews by Henry Hart Milman published in 1829. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Milman’s work is memorable as the first to respect the Jews’ origins as a tribe of the Levant rather as another group of white Europeans. This attempt to treat people as they are rather than how they are perceived may have been flawed as pioneering works often are but it formed a foundation for future historians to build upon. By this point of the story we must wonder why the realms of Europe could not see what a valuable addition the Jews were to their civilization.

Time: 1250

Place: England

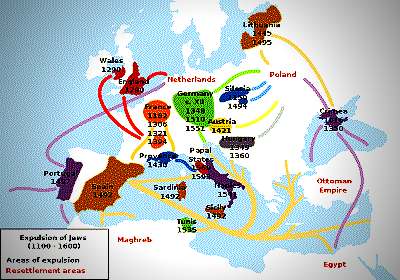

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

Jewish history has a melancholy sameness — perpetual exactions, the means of enforcing them differing only in their degrees of cruelty. Under Henry III the Parliament of England began, 1250, to consider that these extraordinary succors ought at least to relieve the rest of the nation. They began to inquire into the King’s resources from this quarter, and the King consented that one of the two justices of the Jews should be appointed by parliament. But the barons thought more of easing themselves than of protecting the oppressed. In 1256 a demand of eight thousand marks was made, under pain of being transported, some at least of the most wealthy, to Ireland; and, lest they should withdraw their families into places of concealment, they were forbidden, under the penalty of outlawry and confiscation, to remove wife or child from their usual place of residence, for their wives and children were now liable to taxation as well as themselves. During the next three years sixty thousand marks more were levied. How, then, was it possible for any traffic, however lucrative, to endure such perpetual exactions?

The reason must be found in the enormous interest of money, which seems to have been considered by no means immoderate at 50 per cent.; certain Oxford scholars thought themselves relieved by being constrained to pay only twopence weekly on a debt of twenty shillings. In fact, the rivalry of more successful usurers seems to have afflicted the Jews more deeply than the exorbitant demands of the King. These were the “Caorsini,” Italian bankers, though named from the town of Cahors, employed by the Pope to collect his revenue. It was the practice of these persons, under the sanction of their principal, to lend money for three months without interest, but afterward to receive 5 per cent, monthly till the debt was discharged; the former device was to exempt them from the charge of usury. Henry III at one time attempted to expel this new swarm of locusts; but they asserted their authority from the Pope, and the monarch trembled.

Nor were their own body always faithful to the Jews. A certain Abraham, who lived at Berkhampstead and Wallingford, with a beautiful wife who bore the heathen name of Flora, was accused of treating an image of the Virgin with most indecent contumely; he was sentenced to perpetual imprisonment, but released, on the intervention of Richard, Earl of Cornwall, on payment of seven hundred marks. He was a man, it would seem, of infamous character, for his brethren accused him of coining, and offered one thousand marks rather than that he should be released from prison. Richard refused the tempting bribe, because Abraham was “his Jew.” Abraham revenged himself by laying information of plots and conspiracies entered into by the whole people, and the more probable charge of concealment of their wealth from the rapacious hands of the King. This led to a strict and severe investigation of their property. At this investigation was present a wicked and merciless Jew, who rebuked the Christians for their tenderness to his brethren, and reproached the King’s officers as gentle and effeminate. He gnashed his teeth, and, as each Jew appeared, declared that he could afford to pay twice as much as was exacted. Though he lied, he was useful in betraying their secret hoards to the King.

The distresses of the King increased, and, as his parliament resolutely refused to maintain his extravagant expenditure, nothing remained but to drain still further the veins of the Jews. The office was delegated to Richard, Earl of Cornwall, his brother, whom, from his wealth, the King might consider possessed of some secret for accumulating riches from hidden sources. The rabbi Elias was deputed to wait on the Prince, expressing the unanimous determination of all the Jews to quit the country rather than submit to further burdens: “Their trade was ruined by the Caorsini, the Pope’s merchants — the Jew dared not call them usurers — who heaped up masses of gold by their money-lending; they could scarcely live on the miserable gains they now obtained; if their eyes were torn out and their bodies flayed, they could not give more.” The old man fainted at the close of his speech, and was with difficulty revived.

Their departure from the country was a vain boast, for whither should they go? The edicts of the King of France had closed that country against them, and the inhospitable world scarcely afforded a place of refuge. Earl Richard treated them with leniency and accepted a small sum. But the next year the King renewed his demands; his declaration affected no disguise: “It is dreadful to imagine the debts to which I am bound. By the face of God, they amount to two hundred thousand marks; if I should say three hundred thousand, I should not go beyond the truth. Money I must have, from any place, from any person, or by any means.” The King’s acts display as little dignity as his proclamation. He actually sold or mortgaged to his brother Richard all the Jews in the realm for five thousand marks, giving him full power over their property and persons; our records still preserve the terms of this extraordinary bargain and sale.

Popular opinion, which in the worst times is some restraint upon the arbitrary oppressions of kings, in this case would rather applaud the utmost barbarity of the monarch than commiserate the wretchedness of the victims; for a new tale of the crucifixion of a Christian child, called Hugh of Lincoln, was now spreading horror throughout the country. The fact was confirmed by a solemn trial and the conviction and execution of the criminals. It was proved, according to the mode of proof in those days, that the child had been stolen, fattened on bread and milk for ten days, and crucified with all the cruelties and insults of Christ’s Passion, in the presence of all the Jews in England, summoned to Lincoln for this especial purpose; a Jew of Lincoln sat in judgment as Pilate. But the earth could not endure to be an accomplice in the crime; it cast up the buried remains, and the affrighted criminals were obliged to throw the body into a well, where it was found by the mother. A great part of this story refutes itself, but among the ignorant and fanatic Jews there might be some who, exasperated by the constant repetition of this charge, might brood over it so long as at length to be tempted to its perpetration.

| Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.