Today’s installment concludes Slavery Injected Into Virginia,

the name of our combined selection from Charles Campbell and John M. Ludlow. The concluding installment is by John M. Ludlow. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed four thousand words from great works of history. Congratulations!

Previously in Slavery Injected Into Virginia.

Time: 1619

Place: Virginia

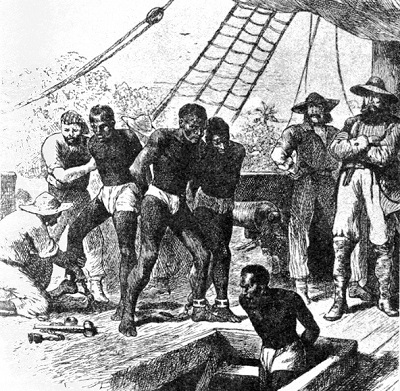

In the same spirit England dealt with her colonies. When Virginia imposed a tax on the import of negroes, the law had to give way before the interest of the African Company. The same course was followed many years later toward South Carolina, when an act of the provincial Assembly laying a heavy duty on imported slaves was vetoed by the crown (1761). Indeed, the title to a political tract published in 1745, The African Slave Trade, the Great Pillar and Support of the British Plantation Trade in America, appears fairly to express the prevalent feeling of the mother-country on the subject before the War of Independence. The most remarkable relaxation of the navigation laws in the eighteenth century was the throwing open the slave trade by the act “for extending and improving the trade to Africa,” which, after reciting that “the trade to and from Africa is very advantageous to Great Britain, and necessary for the supplying the plantations and colonies thereunto belonging with a sufficient number of negroes at reasonable rates,” enacted that it should be lawful “for all his majesty’s subjects to trade and traffick to and from any port or place in Africa, between the port of Sallee in South Barbary and the Cape of Good Hope.” By 1763 there were about three hundred thousand negroes in the North American colonies.

It seemed at first as if the black man would gain by the Revolution. The mulatto Attucks was one of the victims of the Boston Massacre, and was buried with honor among the “martyrs of liberty.” At the first call to arms the negroes freely enlisted; but a meeting of the general officers decided against their enlistment in the new army of 1775. The free negroes were greatly dissatisfied. Lest they should transfer their services to the British, Washington gave leave to enlist them, and it is certain that they served throughout the war, shoulder to shoulder with white men. At the battle of Monmouth there were more than seven hundred black men in the field. Rhode Island formed a battalion of negroes, giving liberty to every slave enlisting, with compensation to his owner; and the battalion did good service. But Washington always considered the policy of arming slaves “a moot point,” unless the enemy set the example; and though Congress recommended Georgia and South Carolina to raise three thousand negroes for the war, giving full “compensation to the proprietors of such negroes,” South Carolina refused to do so, and Georgia had been already overrun by the British when the advice was brought.

Notwithstanding the early adoption of a resolution against the importation of slaves into any of the thirteen colonies (April 6, 1776), Jefferson’s fervid paragraph condemning the slave trade, and by implication slavery, was struck out of the Declaration of Independence in deference to South Carolina and Georgia, and a member from South Carolina declared that “if property in slaves should be questioned there must be an end to confederation.” The resolution of Congress itself against the slave trade bound no single State, although a law to this effect was adopted by Virginia in 1778, and subsequently by all the other States; but this was so entirely a matter of State concernment that neither was any prohibition of the trade contained in the Articles of Confederation, nor was any suffered to be inserted in the treaty of peace.

The feeling against slavery itself was strong in the North. Vermont, in forming a constitution for herself in 1777, allowed no slavery, and was punished for doing so when she applied for admission as a State with the consent of New York, from which she had seceded in 1781: the Southern States refusing to admit her for the present, lest the balance of power should be destroyed. Massachusetts and Pennsylvania, directly or indirectly, abolished slavery in 1780, New Hampshire in 1783. They were followed the next year by Connecticut and Rhode Island, so that by 1784 slavery would be practically at an end in New England and Pennsylvania. Other States — Virginia, Delaware, New Jersey — went no further than to pass laws for allowing voluntary emancipation. In strange contrast to these, Virginia is found in 1780 offering a negro by way of bounty to any white man enlisting for the war. The great Virginians of the day, however — Jefferson, Patrick Henry, George Mason — were opposed to slavery, and large numbers of slaves were emancipated in the State.

So much and no more did the black man get from the Americans. It seemed at first, when Lord Dunmore issued his proclamation offering freedom to all slaves who should join the British standard, as if they were to get much more from England. Accordingly, Governor Rutledge of South Carolina declared in 1780 that the negroes offered up their prayers in favor of England. But although Lord Dunmore persisted in recommending the arming and emancipation of the blacks, neither the ministry at home nor the British officers would enter into the plan. Lord George Germain authorized the confiscation and sale of slaves, even of those who voluntarily followed the troops. Indians were encouraged to catch them and bring them in; they were distributed as prizes and shipped to the West Indies, two thousand at one time, being valued at two hundred fifty silver dollars each. The English name became a terror to the black man, and when Greene took the command they flocked in numbers to his standard. The terms of the peace forbade the British troops to carry away “negroes or other property.” Whichever side he might fight for, the poor black man earned no gratitude.

Yet in little more than three-quarters of a century the political complications arising out of the wrongs inflicted on him were to involve the States that had just won their independence in a civil war in comparison with which the struggle to throw off the yoke of the mother-country would appear almost as child’s play.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our selections on Slavery Injected Into Virginia by two of the most important authorities of this topic:

- Charles Campbell

- John M. Ludlow

Charles Campbell begins here. John M. Ludlow begins here.

This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Slavery Injected Into Virginia here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.