Queen Elizabeth had been a partner in the second voyage of Sir John Hawkins, the first English slave-captain.

Continuing Slavery Injected Into Virginia,

our selection from John M. Ludlow. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in 1.5 easy 5 minute installments.

First we conclude our selection by Charles Campbell.

Previously in Slavery Injected Into Virginia.

Time: 1619

Place: Virginia

The Counterblast to Tobacco was first printed in quarto, without name or date, at London, 1616. In the frontpiece were engraved the tobacco-pipes, cross-bones, death’s-head, etc. It is not improbable that it was directly intended to foment the popular prejudice against Sir Walter Raleigh, who was put to death in the same year (1616). James alludes to the introduction of the use of tobacco and to Raleigh as follows: “It is not so long since the first entry of this abuse among us here, as that this present age cannot very well remember both the first author and the form of the first introduction of it among us. It was neither brought in by king, great conqueror, nor learned doctor of physic. With the report of a great discovery for a conquest, some two or three savage men were brought in together with this savage custom; but the pity is, the poor wild barbarous men died, but that vile barbarous custom is still alive, yea, in fresh vigor, so as it seems a miracle to me how a custom springing from so vile a ground, and brought in by a father so generally hated, should be welcomed upon so slender a warrant.”

The King thus reasons against the Virginia staple: “Secondly, it is, as you use or rather abuse it, a branch of the sin of drunkenness, which is the root of all sins, for as the only delight that drunkards love any weak or sweet drink, so are not those (I mean the strong heat and fume) the only qualities that make tobacco so delectable to all the lovers of it? And as no man loves strong heavy drinks the first day (because nemo repente fuit turpissimus), but by custom is piece and piece allured, while in the end a drunkard will have as great a thirst to be drunk as a sober man to quench his thirst with a draught when he hath need of it; so is not this the true case of all the great takers of tobacco, which therefore they themselves do attribute to a bewitching quality in it? Thirdly, is it not the greatest sin that all of you, the people of all sorts of this kingdom, who are created and ordained by God to bestow both your persons and goods for the maintenance both of the honor and safety of your King and commonwealth, should disable yourself to this shameful imbecility, that you are not able to ride or walk the journey of a Jew’s Sabbath, but you must have a reeky coal brought you from the next poorhouse to kindle your tobacco with? whereas he cannot be thought able for any service in the wars that cannot endure ofttimes the want of meat, drink, and sleep; much more then must he endure the want of tobacco.”

A curious tractate on tobacco, by Dr. Tobias Venner, was published at London in 1621. The author was a graduate of Oxford, and a physician at Bath, and is mentioned in the Oxoniæ Athenienses.

The amount of tobacco imported in 1619 into England from Virginia, being the entire crop of the preceding year, was, as before said, twenty thousand pounds. At the end of seventy years there were annually imported into England more than fifteen million of pounds of it, from which a revenue of upward of one hundred thousand pounds was derived.

In April, 1621, the House of Commons debated whether it was expedient to prohibit the importation of tobacco entirely; and they determined to exclude all save from Virginia and the Somer Isles. It was estimated that the consumption of England amounted to one thousand pounds per diem. This seductive narcotic leaf, which soothes the mind and quiets its perturbations, has found its way into all parts of the habitable globe, from the sunny tropics to the snowy regions of the frozen pole. Its fragrant smoke ascends alike to the blackened rafters of the lowly hut and the gilded ceilings of luxurious wealth.

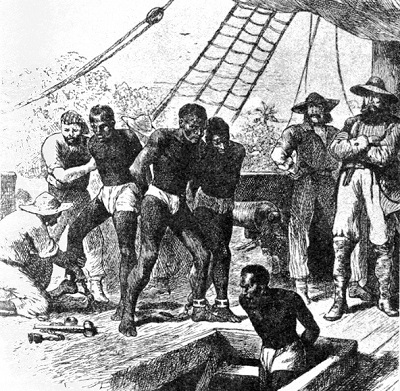

The first negro slaves were brought by Dutchmen for sale into Virginia in 1619. The New England public was at first opposed to the practice of negro slavery, and there is even a record of a slave, who had been sold by a member of the Boston Church, being ordered to be sent back to Africa (1645). Yet negro slaves were to be found in New England as early as 1638. Massachusetts and Connecticut recognized the lawfulness of slavery; Massachusetts, however, only when voluntary or in the case of captives taken in war. Rhode Island, more generous, made illegal the perpetual service of “black mankind,” requiring them to be set free after two years, the period of white men’s indentures — a condition which, however, would only tend to the working slaves to death in the allotted time. But although there was no importation of negroes on any considerable scale into New England, the ships by which the slave trade was mainly carried on were those from Massachusetts and Rhode Island, which carried rum to Africa, and brought back slaves to the West Indies and the southern colonies. In Maryland slavery had been established at once; in South Carolina it came into birth with the colony itself. The attempt to exclude it from Georgia failed.

The guilt of the institution cannot, however, be fairly charged on the colonists. Queen Elizabeth had been a partner in the second voyage of Sir John Hawkins, the first English slave-captain. James I chartered a slave-trading company (1618); Charles I a second (1631); Charles II a third (1663), of which the Duke of York was president, and again a fourth, in which he himself, as well as the Duke, was a subscriber. Nor did the expulsion of the Stuarts cause any change of feeling in this respect. England’s sharpest stroke of business at the Peace of Utrecht (1713) was the obtaining for herself the shameful monopoly of the “Asiento” — the slave trade with the Spanish West Indies — undertaking “to bring into the West Indies of America belonging to his Catholic majesty, in the space of thirty years, one hundred forty-four thousand negroes,” at the rate of forty-eight hundred a year, at a fixed rate of duty, with the right to import any further number at a lower rate. As nearly the whole shores of the Gulf of Mexico were still Spanish, England thus contributed to build up slavery in most of the future Southern States of the Union. Whether for foreign or for English colonies, it is reckoned that, from 1700 to 1750, English ships carried away from Africa probably a million and a half of negroes, of whom one-eighth never lived to see the opposite shore.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Charles Campbell begins here. John M. Ludlow begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.