On September 19, 1783, the King, Queen, the court, and innumerable people of every rank and age assembled at Versailles, Jacques Montgolfier being present to explain every particular.

The First Balloon Ascension, featuring a series of excerpts selected from Astra Castra : Experiments and Adventures in the Atmosphere by Hatton Turnor published in 1865.

Previously in The First Balloon Ascension.

Time: 5 pm, August 27, 1783

Place: Paris

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

A similar tale has lately been told me as having occurred in Persia, where a fire-balloon was let off by some French visitors to the Shah’s palace at Teheran, when it alighted. No less than three shots were fired at it when on the ground, before anyone would venture nearer.

It is no wonder, then, that the paternal government of France deemed it necessary to publish the following “avertissement” to the public:

“INFORMATION FOR THE PEOPLE ON THE ASCENT OF BALLOONS, OR GLOBES, IN THE AIR

“PARIS, August 27, 1783.

“The one in question has been raised in Paris this said day, August 27, 1783, at 5 P.M., in the Champ-de-Mars.

“A discovery has been made, which the Government deems it right to make known, so that alarm be not occasioned to the people.

“On calculating the different weights of inflammable and common air, it has been found that a balloon filled with inflammable air will rise toward heaven till it is in equilibrium with the surrounding air; which may not happen till it has attained a great height.

“The first experiment was made at Annonay, in Vivarais, by Messrs. Montgolfier, the inventors. A globe formed of canvas and paper, 105 feet in circumference, filled with inflammable air, reached an incalculated height.

“The same experiment has just been renewed at Paris (August 27th, 5 P.M.), in presence of a great crowd. A globe of taffeta, covered with elastic gum, thirty-six feet in circumference, has risen from the Champ-de-Mars, and been lost to view in the clouds, being borne in a northeasterly direction; one cannot foresee where it will descend.

“It is proposed to repeat these experiments on a larger scale. Any one who shall see in the sky such a globe (which resembles the moon in shadow) should be aware that, far from being an alarming phenomenon, it is only a machine, made of taffeta or light canvas, covered with paper, that cannot possibly cause any harm, and which will some day prove serviceable to the wants of society.

“Read and approved, September 3, 1783. “DE SAUVIGNY. “Permission for printing. LENOIR.”

Balloons made of paper and goldbeater’s-skin were now sent up by amateurs from all places which this intelligence reached; and in September another important step was made, an account of which, and of the ascents which followed during the next two years, I take from the quaint but graphic History of Aerostation, by Tiberius Cavallo.

Tiberius Cavallo was an electrician and natural philosopher, born at Naples, 1749. He came to England in 1771, where he devoted his time to science and literature till his death, in 1809.

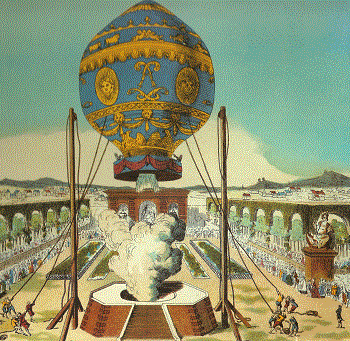

On September 19, 1783, the King, Queen, the court, and innumerable people of every rank and age assembled at Versailles, Jacques Montgolfier being present to explain every particular. About one o’clock the fire was lighted, in consequence of which the machine began to swell, acquired a convex form, soon stretched itself on every side, and in eleven minutes’ time, the cords being cut, it ascended, together with a wicker cage, which was fastened to it by a rope. In this cage they had put a sheep, a cock, and a duck, which were the first animals that ever ascended into the atmosphere with an aerostatic machine. When the machine went up, its power of ascension or levity was six hundred ninety-six pounds, allowing for the cage and animals.

The machine raised itself to the height of about one thousand four hundred forty feet; and being carried by the wind, it fell gradually in the wood of Vaucresson, at the distance of ten thousand two hundred feet from Versailles, after remaining in the atmosphere only eight minutes. Two game-keepers, who were accidentally in the wood, saw the machine fall very gently, so that it just bent the branches of the trees upon which it alighted. The long rope to which the cage was fastened, striking against the wood, was broken, and the cage came to the ground without hurting in the least the animals that were in it, so that the sheep was even found feeding. The cock, indeed, had its right wing somewhat hurt; but this was the consequence of a kick it had received from the sheep, at least half an hour before, in presence of at least ten witnesses.

It has been sufficiently demonstrated by experiments that little or no danger is to be apprehended by a man who ascends with such an aerostatic machine. The steadiness of the aerostat while in the air, its gradual and gentle descent, the safety of the animals that were sent up with it in the last-mentioned experiment, and every other observation that could be deduced from all the experiments hitherto made in this new field of inquiry seem more than sufficient to expel any fear for such an enterprise; but as no man had yet ventured in it, and as most of the attempts at flying, or of ascending into the atmosphere, on the most plausible schemes, had from time immemorial destroyed the reputation or the lives of the adventurers, we may easily imagine and forgive the hesitation that men might express, of going up with one of those machines: and history will probably record, to the remotest posterity, the name of M. Pilectre de Rozier, who had the courage of first venturing to ascend with a machine, which in a few years hence the most timid woman will perhaps not hesitate to trust herself to.

The King, aware of the difficulties, ordered that two men under sentence of death should be sent up; but Pilectre de Rozier was indignant, saying, “Eh quoi! de vils criminels auraient les premiers la gloire de s’elever dans les airs! Non, non cela ne sera point!” (“What! Vile criminals to have the glory of the first aerial ascension! No, not on any account!”) He stirs up the city in his behalf, and the King at length yields to the earnest entreaties of the Marquis d’Arlandes, who said that he would accompany him.

Scarce ten months had elapsed since M. Montgolfier made his first aerostatic experiment, when M. Pilectre de Rozier publicly offered himself to be the first adventurer in the newly invented aerial machine. His offer was accepted; his courage remained undaunted; and on October 15, 1783, he actually ascended, to the astonishment of a gazing multitude. The following are the particulars of this experiment:

“The accident which happened to the aerostatic machine at Versailles, and its imperfect construction, induced M. Montgolfier to construct another machine, of a larger size and more solid. With this intent, sufficient time was allowed for the work to be properly done; and by October 10th the aerostat was completed, in a garden in the Faubourg St.-Antoine. It had an oval shape; its diameter being about forty-eight feet, and its height about seventy-four. The outside was elegantly painted and decorated with the signs of the zodiac, with the cipher of the King’s name in fleurs-de-lis, etc. The aperture or lower part of the machine had a wicker gallery about three feet broad, with a balustrade both within and without about three feet high. The inner diameter of this gallery, and of the aperture of the machine, the neck of which passed through it, was near sixteen feet. In the middle of this aperture an iron grate or brazier was supported by chains which came down from the sides of the machine.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.