Today’s installment concludes Battle of Tours,

our selection from Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World by Edward S. Creasy published in 1851. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of four thousand words. Congratulations!

Previously in Battle of Tours.

Time: 732

Place: Tours, France

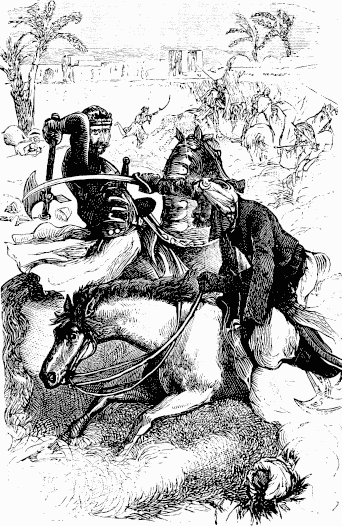

Public domain image from Wikipedia

In addition to his cardinal military virtues Abderrahman is described by the Arab writers as a model of integrity and justice. The first two years of his second administration in Spain were occupied in severe reforms of the abuses which under his predecessors had crept into the system of government, and in extensive preparations for his intended conquest in Gaul. Besides the troops which he collected from his province, he obtained from Africa a large body of chosen Berber cavalry, officered by Arabs of proved skill and valor; and in the summer of 732 he crossed the Pyrenees at the head of an army which some Arab writers rate at eighty thousand strong, while some of the Christian chroniclers swell its numbers to many hundreds of thousands more. Probably the Arab account diminishes, but of the two keeps nearer to the truth.

They tell us how there was war between the count of the Frankish frontier and the Moslems, and how the count gathered together all his people, and fought for a time with doubtful success. “But,” say the Arabian chroniclers, “Abderrahman drove them back; and the men of Abderrahman were puffed up in spirit by their repeated successes, and they were full of trust in the valor and the practice in war of their Emir. So the Moslems smote their enemies, and passed the river Garonne, and laid waste the country, and took captives without number. And that army went through all places like a desolating storm. Prosperity made these warriors insatiable. At the passage of the river Abderrahman overthrew the count, and the count retired into his stronghold, but the Moslems fought against it, and entered it by force and slew the count; for everything gave way to their cymiters, which were the robbers of lives.

All the nations of the Franks trembled at that terrible army, and they betook them to their king ‘Caldus,’ and told him of the havoc made by the Moslem horsemen, and how they rode at their will through all the land of Narbonne, Toulouse, and Bordeaux, and they told the King of the death of their count. Then the King bade them be of good cheer, and offered to aid them. And in the 114th year[1] he mounted his horse, and he took with him a host that could not be numbered, and went against the Moslems. And he came upon them at the great city of Tours. And Abderrahman and other prudent cavaliers saw the disorder of the Moslem troops, who were loaded with spoil; but they did not venture to displease the soldiers by ordering them to abandon everything except their arms and war-horses. And Abderrahman trusted in the valor of his soldiers, and in the good fortune which had ever attended him. But, the Arab writer remarks, such defect of discipline always is fatal to armies.

[1: Of the Hegira.]

So Abderrahman and his host attacked Tours to gain still more spoil, and they fought against it so fiercely that they stormed the city almost before the eyes of the army that came to save it, and the fury and the cruelty of the Moslems toward the inhabitants of the city were like the fury and cruelty of raging tigers. It was manifest,” adds the Arab, “that God’s chastisement was sure to follow such excesses, and Fortune thereupon turned her back upon the Moslems.

Near the river Owar,[2] the two great hosts of the two languages and the two creeds were set in array against each other. The hearts of Abderrahman, his captains, and his men, were filled with wrath and pride, and they were the first to begin the fight. The Moslem horsemen dashed fierce and frequent forward against the battalions of the Franks, who resisted man-fully, and many fell dead on either side, until the going down of the sun. Night parted the two armies, but in the gray of the morning the Moslems returned to the battle. Their cavaliers had soon hewn their way into the center of the Christian host. But many of the Moslems were fearful for the safety of the spoil which they had stored in their tents, and a false cry arose in their ranks that some of the enemy were plundering the camp; whereupon several squadrons of the Moslem horsemen rode off to protect their tents. But it seemed as if they fled, and all the host was troubled.

[2: Probably the Loire.]

And while Abderrahman strove to check their tumult and to lead them back to battle, the warriors of the Franks came around him, and he was pierced through with many spears, so that he died. Then all the host fled before the enemy and many died in the flight. This deadly defeat of the Moslems, and the loss of the great leader and good cavalier Abderrahman, took place in the hundred and fifteenth year.”[3]

[3: An. Heg.]

It would be difficult to expect from an adversary a more explicit confession of having been thoroughly vanquished than the Arabs here accord to the Europeans. The points on which their narrative differs from those of the Christians — as to how many days the conflict lasted, whether the assailed city was actually rescued or not, and the like — are of little moment compared with the admitted great fact that there was a decisive trial of strength between Frank and Saracen, in which the former conquered. The enduring importance of the battle of Tours in the eyes of the Moslems is attested not only by the expressions of “the deadly battle” and “the disgraceful overthrow” which their writers constantly employ when referring to it, but also by the fact that no more serious attempts at conquest beyond the Pyrenees were made by the Saracens.

Charles Martel and his son and grandson were left at leisure to consolidate and extend their power. The new Christian Roman Empire of the West, which the genius of Charlemagne founded, and throughout which his iron will imposed peace on the old anarchy of creeds and races, did not indeed retain its integrity after its great ruler’s death. Fresh troubles came over Europe, but Christendom, though disunited, was safe. The progress of civilization, and the development of the nationalities and governments of modern Europe, from that time forth went forward in not uninterrupted, but ultimately certain, career.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Battle of Tours by Edward S. Creasy from his book Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World published in 1851. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Battle of Tours here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.