He received the compliments due to his courage and audacity, having shown the world the accomplishment of that which had been for ages desired, but attempted in vain.

Today’s installment concludes The First Balloon Ascension,

featuring a series of excerpts selected from Astra Castra : Experiments and Adventures in the Atmosphere by Hatton Turnor published in 1865.

Previously in First Balloon Ascension.

Time: 5 pm, August 27, 1783

Place: Paris

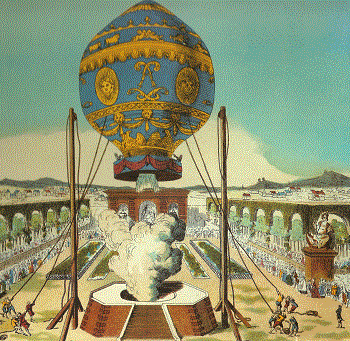

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

“In this construction, when the machine was in the air, with a fire lighted in the grate, it was easy for a person who stood in the gallery, and had fuel with him, to keep up the fire in the mouth of the machine, by throwing the fuel on the grate through port-holes made in the neck of the machine. By this means it was expected, as indeed it was found by experience, that the machine might have been kept up as long as the person in its gallery thought proper, or while he had fuel to supply the fire with. The weight of this aerostat was upward of 16,000 pounds.

“On Wednesday, October 15th, this memorable experiment was performed. The fire being lighted, and the machine inflated, M. Pilectre de Rozier placed himself in the gallery, and, after a few trials close to the ground, he desired to ascend to a great height; the machine was accordingly permitted to rise, and it ascended as high as the ropes, which were purposely placed to detain it, would allow, which was about eighty-four feet from the ground. There M. de Rozier kept the machine afloat during four minutes twenty-five seconds, by throwing straw and wool into the grate to keep up the fire; then the machine descended very gently; but such was its tendency to ascend, that after touching the ground, the moment M. de Rozier came out of the gallery, it rebounded again to a considerable height. The intrepid adventurer, returning from the sky, assured his friends, and the multitude that gazed on him with admiration, with wonder, and with fear, that he had not experienced the least inconvenience, either in going up, in remaining there, or in descending; no giddiness, no incommoding motion, no shock whatever. He received the compliments due to his courage and audacity, having shown the world the accomplishment of that which had been for ages desired, but attempted in vain.

“On October 17th, M. Pilectre de Rozier repeated the experiment with nearly the same success as he had two days before. The machine was elevated to about the same height, being still detained by ropes; but the wind being strong, it did not sustain itself so well, and consequently did not afford so fine a spectacle to the concourse of people, which at this time was much greater than at the preceding experiment.

“On the Sunday following, which was the 19th, the weather proving favorable, M. Montgolfier employed his machine to make the following experiments. At half past four o’clock the machine was filled, in five minutes’ time; then M. Pilectre de Rozier placed himself in the gallery, a counterpoise of 100 pounds being put in the opposite side of it, to preserve the balance. The size of the gallery had now been diminished. The machine was permitted to ascend to the height of about 210 feet, where it remained during six minutes, not having any fire in the grate; and then it descended very gently.

“Soon after, everything remaining as before, except that now a fire was put into the grate, the machine was permitted to ascend to about 262 feet, where it remained stationary during eight minutes and a half. On pulling it down, a gust of wind carried it over some large trees in an adjoining garden, where it would have been in great danger had not M. de Rozier, with great presence of mind and address, increased the fire by throwing some straw upon it; by which means the machine was extricated from so dangerous a situation, and rose majestically to its former situation, among the acclamations of the spectators. On descending, M. de Rozier threw some straw upon the fire, which made the machine ascend once more, remaining up for about the same length of time.

“This experiment showed that the aerostat may be made to ascend and descend at the pleasure of those who are in it; to effect which, they have nothing more to do than to increase or diminish the fire in the grate; which was an important point in the subject of aerostation.

“After this, the machine was raised again with two persons in its gallery, M. PilC”tre de Rozier and M. Girond de Villette, the latter of whom was therefore the second aerostatic adventurer. The machine ascended to the height of about 300 feet, where it remained perfectly steady for at least nine minutes, hovering over Paris, in sight of its numerous inhabitants, many of whom could plainly distinguish, through telescopes, the aerostatic adventurers, and especially M. de Rozier, who was busy in managing the fire. When the machine came down, the Marquis d’Arlandes, a major of infantry, took the place of M. Villette, and the balloon was sent up once more. This last experiment was attended with the same success as the preceding; which proved that the persons who ascended with the machine did not suffer the least inconvenience, owing to the gradual and gentle ascent and descent of the machine, and to its steadiness or equilibrium while it remained in the air.

“If we consider for a moment the sensation which these first aerial adventurers must have felt in their exalted situation, we can almost feel the contagion of their thrilling experience ourselves. Imagine a man elevated to such a height, into immense space, by means altogether new, viewing under his feet, like a map, a vast tract of country, with one of the greatest existing cities — the streets and environs of which were crowded with spectators–attentive to him alone, and all expressing in every possible manner their amazement and anxiety. Reflect on the prospect, the encomiums, and the consequences; then see if your mind remains in a state of quiet indifference.

“An instructive observation may be derived from these experiments; which is, that when an aerostatic machine is attached to the earth by ropes–especially when it is at a considerable height–the wind, blowing on it, will drive it in its own horizontal direction; so that the cords which hold the machine must make an angle with the horizon (which is greater when the wind is stronger, and contrariwise); in consequence of which the machine must be severely strained, it being acted on by three forces in three different directions; namely, its power of ascension, the tension of the ropes, which is opposite to the first, and the action of the wind, which is across the other two. It is therefore infinitely more judicious to abandon the machine entirely to the air, because it will then stand perfectly balanced, and, therefore, under no strain whatever.”

In consequence of the report of the foregoing experiments, signed by the commissaries of the Academy of Sciences, that learned and respectable body ordered: (1) That the said report should be printed and published; and (2) that the annual prize of six hundred livres, from the fund provided by an anonymous citizen, be given to Messrs. Montgolfier, for the year 1783.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on First Balloon Ascension by Hatton Turnor from his book Astra Castra : Experiments and Adventures in the Atmosphere published in 1865. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

Hello ~ Awesome blog ~ Thanks