Shortly after midnight the Queen-mother rose and went to the King’s chamber, attended only by one lady, the Duchess of Nemours, whose thirst for revenge was to be satisfied at last in the St. Bartholomew Day massacre.

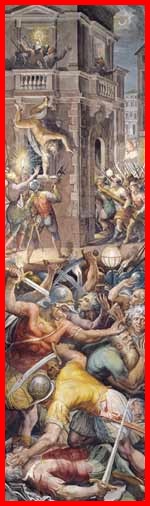

The St. Bartholomew Day Massacre, featuring a series of excerpts selected from works by Henry White and Isaac Disraeli. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The St. Bartholomew Day Massacre. Today’s installment is by Henry White.

Time: 1572

Place: Paris

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

That evening the King had supped in public, and, the hours being much earlier than with us, the time was probably between six and seven. The courtiers admitted to witness the meal appear to have been as numerous as ever, Huguenots as well as Catholics, victims and executioners. Charles, who retired before eight o’clock, kept Francis, Count of La Rochefoucault, with him for some time, as if unwilling to part with him. “Do not go,” he said; “it is late. We will sit and talk all night.”

“Excuse me, sire, I am tired and sleepy.”

“You must stay; you can sleep with my valets.” But as Charles was rather too fond of rough practical jokes, the Count still declined, and went away, suspecting no evil, to pay his usual evening visit to the Dowager Princess of Conde. He must have remained some time in her apartments, for it was past twelve o’clock when he went to bid Navarre good-night. As he was leaving the palace a man stopped him at the foot of the stairs and whispered in his ear. When the stranger left. La Rochefoucault bade Mergey, one of his suite, to whom we are indebted for these particulars, return and tell Henry that Guise and Nevers were about the city. During Mergey’s brief absence something more appears to have been told the Count, for he returned upstairs with Nancay, captain of the guard, who, lifting the tapestry which closed the entrance to Navarre’s antechamber, looked for some time at the gentlemen within, playing at cards or dice, others talking. At last he said: “Gentlemen, if any one of you wishes to retire, you must do so at once, for we are going to shut the gates.” No one moved, as it would appear, for at Charles’ express desire, it is said — which is scarcely probable — these Huguenot gentlemen had gathered round the King of Navarre to protect him against any outrage of the Guises. In the court-yard Mergey found the guard under arms. “M. Rambouillet, who loved me,” he continues, “was sitting by the wicket as I passed out. He took my hand, and with a piteous look said: ‘Adieu, Mergey; adieu, my friend,’ not daring to say more, as he told me afterward.”

Coligny’s hotel had been crowded all day by visitors; the Queen of Navarre had paid him a visit, and most of the gentlemen in Paris, Catholic as well as Huguenot, had gone to express their sympathy. For the Frenchman is a gallant enemy and respects brave men; and the foul attempt upon the admiral, whom they had so often encountered on the battle-field, was felt as a personal injury. A council had been held that day, at which the propriety of removing in a body from Paris and carrying the admiral with them had again been discussed. Navarre and Conde opposed the proposition, and it was finally resolved to petition to the King “to order all the Guisians out of Paris, because they had too much sway with the people of the town.” One Bouchavannnes, a traitor, was among them, greedily listening to every word, which he reported to Anjou, strengthening him in his determination to make a clean sweep that very night.

As the evening came on, the admiral’s visitors took their leave. Teligny, his son-in-law, was the last to quit his bedside. To the question whether the admiral would like any of them to keep watch in his house during the night, he answered, says the contemporary biographer, “that it was labor more than needed, and gave them thanks with very loving words.” It was after midnight when Teligny and Guerchy departed, leaving Ambrose ParE and Pastor Merlin with the wounded man. There were besides in the house two of his gentlemen, Cornaton, afterward his biographer, and La Bonne; his squire Yolet, five Switzers belonging to the King of Navarre’s guard, and about as many domestic servants. It was the last night on earth for all except two of that household.

It is strange that the arrangements in the city, which must have been attended with no little commotion, did not rouse the suspicion of the Huguenots. Probably, in their blind confidence, they trusted implicitly in the King’s word that these movements of arms and artillery, these postings of guards and midnight musters, were intended to keep the Guisian faction in order. There is a story that some gentlemen, aroused by the measured tread of the soldiers and the glare of torches — for no lamps then lit up the streets of Paris — went outdoors and asked what it meant. Receiving an unsatisfactory reply, they proceeded to the Louvre, where they found the outer court filled with armed men, who, seeing them without the white cross and the scarf, abused them as “accursed Huguenots,” whose turn would come next. One of them who replied to this insolent threat, was immediately run through with a spear. This, if the incident be true, occurred about one o’clock on Sunday morning, August 24th, the festival of St. Bartholomew.

Shortly after midnight the Queen-mother rose and went to the King’s chamber, attended only by one lady, the Duchess of Nemours, whose thirst for revenge was to be satisfied at last. She found Charles pacing the room in one of those fits of passion which he at times assumed to conceal his infirmity of purpose. At one moment he swore he would raise the Huguenots and call them to protect their sovereign’s life as well as their own. Then he burst out into violent imprecations against his brother Anjou, who had entered the room but did not dare say a word. Presently the other conspirators arrived — Guise, Nevers, Birague, De Retz, and Tavannes. Catherine alone ventured to interpose, and, in a tone of sternness well calculated to impress the mind of her weak son, she declared that there was now no turning back: “It is too late to retreat, even were it possible. We must cut off the rotten limb, hurt it ever so much; if you delay, you will lose the finest opportunity God ever gave man of getting rid of his enemies at a blow.” And then, as if struck with compassion for the fate of her victims, she repeated in a low tone — as if talking to herself — the words of a famous Italian preacher, which she had often been heard to quote before: “E la pieta lor ser crudele, e la crudelta lor ser pietosa” (“Mercy would be cruel to them, and cruelty merciful”). Catherine’s resolution again prevailed over the King’s weakness, and, the final orders being given, the Duke of Guise quitted the Louvre, followed by two companies of arquebusiers and the whole of Anjou’s guard.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information on the St. Bartholomew Day Massacre here and here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.