Sully, the future great minister was 12 on St. Bartholomew Day, 1572. One of the individuals in the Saint Bartholomew Day Massacre stories.

Continuing The Saint Bartholomew Day Massacre,

with a selection The Massacre of Bartholomew by Henry White published in 1868. This selection is presented in 7.5 easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The St. Bartholomew Day Massacre. Today’s installment is by Henry White.

Time: 1572

Place: Paris

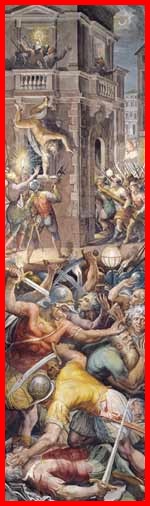

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Mezeray writes that seven hundred or eight hundred people had taken refuge in the prisons, hoping they would be safe “under the wings of Justice”; but the officers selected for this work had brought them into the fitly named “Valley of Misery,” and there beat them to death with clubs and threw their bodies into the river. The Venetian ambassador corroborates this story, adding that they were murdered in batches of ten. Where all were cruel, some few persons distinguished themselves by especial ferocity. A gold-beater, named Crozier, one of those prison-murderers, bared his sinewy arm and boasted of having killed four thousand persons with his own hands. Another man — for the sake of human nature we would fain wish him to be the same — affirmed that unaided he had “dispatched” eighty Huguenots in one day. He would eat his food with hands dripping with gore, declaring “that it was an honor to him, because it was the blood of heretics.” On Tuesday a butcher, Crozier’s comrade, boasted to the King that he had killed one hundred fifty the night before. Coconnas, one of the mignons of Anjou, prided himself on having ransomed from the populace as many as thirty Huguenots, for the pleasure of making them abjure, and then killing them with his own hand, after he had “secured them for hell.”

About seven o’clock the King was at one of the windows of his palace, enjoying the air of that beautiful August morning, when he was startled by shouts of “Kill, kill!” They were raised by a body of guards, who were firing with much more noise than execution at a number of Huguenots who had crossed the river — “to seek the King’s protection,” says one account; “to help the King against the Guises,” says another. Charles, who had just been telling his mother that “the weather seemed to rejoice at the slaughter of the Huguenots,” felt all his savage instincts kindle at the sight. He had hunted wild beasts; now he would hunt men, and, calling for an arquebuse, he fired at the fugitives, who were fortunately out of range. Some modern writers deny this fact, on the ground that the balcony from which Charles is said to have fired was not built until after 1572. Were this true, it would only show that tradition had misplaced the locality. Brantome expressly says the King fired on the Huguenots — not from a balcony, but — “from his bedroom window.” Marshal Tesse heard the story, according to Voltaire, from the man who loaded the arquebuse. Henault, in his chronologique, mentions it with a “dit-on” and it is significant that the passage is suppressed in Latin editions. Simon Goulart, in his contemporary narrative, uses the same words of caution.

Not many of the Huguenot gentlemen escaped from the toils so skillfully drawn round them on that fatal Saturday night: yet there were a few. The Count of Montgomery — the same who was the innocent cause of the death of Henry II — got away safe, having been forewarned by a friend who swam across the river to him. Guise set off in hot pursuit, and would probably have caught him up had he not been waiting for the keys of the city gate. Some sixty gentlemen, also, lodging near him in the Faubourg St. Germain, were the companions of his flight.

Sully, afterward the famous minister of Henry IV, had a narrow escape. He was in his twelfth year, and had gone to Paris in the train of Joan of Navarre for the purpose of continuing his studies. “About three after midnight,” he says, “I was awoke by the ringing of bells and the confused cries of the populace. My governor, St. Julian, with my valet-de-chambre, went out to know the cause; and I never heard of them afterward. They, no doubt, were among the first sacrificed to the public fury. I continued alone in my chamber, dressing myself, when in a few moments my landlord entered, pale and in the most utmost consternation. He was of the Reformed religion, and, having learned what was the matter, had consented to go to mass to save his life and preserve his house from being pillaged. He came to persuade me to do the same and to take me with him. I did not think proper to follow him, but resolved to try if I could gain the College of Burgundy, where I had studied; though the great distance between the house in which I then was and the college made the attempt very dangerous. Having disguised myself in a scholar’s gown, I put a large prayer-book under my arm, and went into the street. I was seized with horror inexpressible at the sight of the furious murderers, running from all parts, forcing open the houses, and shouting out: ‘Kill, kill! Massacre the Huguenots!’ The blood which I saw shed before my eyes, redoubled my terror. I fell into the midst of a body of guards, who stopped and questioned me, and were beginning to use me ill, when, happily for me, the book that I carried was perceived and served me for a passport. Twice after this I fell into the same danger, from which I extricated myself with the same good-fortune. At last I arrived at the College of Burgundy, where a danger still greater than any that I had yet met with awaited me. The porter having twice refused me entrance, I continued standing in the midst of the street, at the mercy of the savage murderers, whose number increased every moment, and who were evidently seeking for their prey, when it came into my head to ask for La Faye, the principal of the college, a good man, by whom I was tenderly beloved. The porter, prevailed upon by some small pieces of money which I put in his hand, admitted me; and my friend carried me to his apartment, where two inhuman priests whom I heard mention ‘Sicilian Vespers,’ wanted to force me from him, that they might cut me in pieces, saying the order was, not to spare even infants at the breast. All the good man could do was to conduct me privately to a distant chamber, where he locked me up. Here I was confined three days, uncertain of my destiny, and saw no one but a servant of my friend’s, who came from time to time to bring me provisions.”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information on Saint Bartholomew Day Massacre stories here and here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.