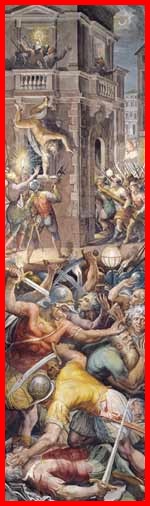

The St. Bartholomew Day Massacre, featuring a series of excerpts selected from works by Henry White and Isaac Disraeli. Saint Bartholomew Day Massacre remorse begins.

Continuing The Saint Bartholomew Day Massacre,

our selection from Curiosities of Literature by Isaac d’Israeli published in 1824. The selection is presented in 1.5 easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

First we conclude Henry White.

Time: 1572

Place: Paris

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Not until the second day does there appear to have been any remorse or pity for the horrors inflicted upon the wretched Huguenots. Elizabeth of Austria, the young Queen who hoped shortly to become a mother, interceded for Conde, and so great was her agitation and distress that her “features were quite disfigured by the tears she had shed night and day.” And, the Duke of Alencon, a youth of by no means lovable character, “wept much,” we are told, “over the fate of those brave captains and soldiers.” For this tenderness he was so bitterly reproached by Charles and his mother that he was forced to keep out of their sight. Alencon was partial to Coligny, and when there was found among the admiral’s papers a report in which he condemned appanages, the grants usually given by the crown to the younger members of the royal family, Catherine exultingly showed it to him — “See what a fine friend he was to you.”

“I know not how far he may have been my friend,” replied the Duke, “but the advice he gave me was very good.”

If Mezeray is to be trusted, Charles broke down on the second day of the massacre. Since Saturday he had been in a state of extraordinary excitement, more like madness than sanity, and at last his mind gave way under the pressure. To his surgeon, Ambrose Pare, me. For these two or three days past, both mind and body have been quite upset. I burn with fever; all around me grin pale blood-stained faces. Ah! Ambrose, if they had but spared the weak and innocent.” A change, indeed, had come over him; be became more restless than ever, his looks savage, his buffoonery coarser and more boisterous. “Ne mai poteva pigliar requie,” says Sigismond Cavalli. Like Macbeth, he had murdered sleep. “I saw the King on my return from Rochelle,” says Brantome, “and found him entirely changed. His features had lost all the gentleness douceur usually visible in them.”

“About a week after the massacre,” says a contemporary, “a number of crows flew croaking round and settled on the Louvre. The noise they made drew everybody out to see them, and the superstitious women infected the King with their own timidity. That very night Charles had not been in bed two hours when he jumped up and called for the King of Navarre, to listen to a horrible tumult in the air; shrieks, groans, yells, mingled with blasphemous oaths and threats, just as they were heard on the night of the massacre. The sound returned seven successive nights, precisely at the same hour.” Juvenal des Ursins tells the story rather differently. “On August 31st I supped at the Louvre with Madame de Fiesque. As the day was very hot we went down into the garden and sat in an arbor by the river. Suddenly the air was filled with a horrible noise of tumultuous voices and groans, mingled with cries of rage and madness. We could not move for terror; we turned pale and were unable to speak. The noise lasted for half an hour, and was heard by the King, who was so terrified that he could not sleep the rest of the night.” As for Catherine; knowing that strong emotions would spoil her digestion and impair her good looks, she kept up her spirits. “For my part,” she said, “there are only six of them on my conscience;” which is a lie, for when she ordered the tocsin to be rung, she must have foreseen the horrors — perhaps not all the horrors — that would ensue.

The massacre began on St. Bartholomew Day, in August, 1572, lasted in France during seven days; that awful event interrupted the correspondence of our court with that of France. A long silence ensued; the one did not dare tell the tale which the other could not listen to. But sovereigns know how to convert a mere domestic event into a political expedient. Charles IX, on the birth of a daughter, sent over an ambassador extraordinary to request Elizabeth to stand as sponsor; by this the French monarch obtained a double purpose; it served to renew his interrupted intercourse with the silent Queen, and alarmed the French Protestants by abating their hopes, which long rested on the aid of the English Queen.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information on Saint Bartholomew Day Massacre remorse here and here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.