Catherine de’ Medici writes letter to repair relations with Elizabeth I of England. This introduces the topic Bartholomew Day Massacre diplomacy.

Today’s installment concludes The Saint Bartholomew Day Massacre,

the name of our combined selection from Henry White and Isaac d’Israeli. The concluding installment, by Isaac d’Israeli from Curiosities of Literature, was published in 1824.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed nine thousand words from great works of history. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Time: 1572

Place: Paris

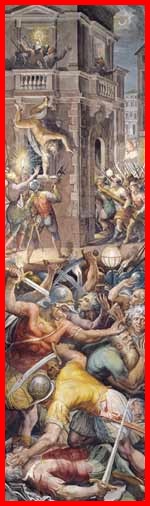

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The following letter, dated February 8, 1573, is addressed by the King to La Motte Fenelon, his resident ambassador at London. The King in this letter minutely details a confidential intercourse with his mother, Catherine de’ Medici, who, perhaps, may have dictated this letter to the secretary, although signed by the King with his own hand. Such minute particulars could only have been known to herself. The Earl of Wolchester (Worcester) was now taking departure, having come to Paris on the baptism of the princess; and accompanied by Walsingham, our resident ambassador, after taking leave of Charles, had the following interview with Catherine de’ Medici. An interview with the young monarch was usually concluded by a separate audience with his mother, who probably was still the directress of his councils.

After Catherine de’ Medici had assured the Earl of Worcester of her great affection for the Queen of England, and the King’s strict intention to preserve it, she took this opportunity of inquiring of the Earl of Worcester the cause of the Queen his mistress’ marked coolness toward them. The narrative becomes now dramatic.

“On this, Walsingham, who always kept close by the side of the Count [Earl of Worcester], here took on himself to answer, acknowledging that the said Count had indeed been charged to speak on this head; and he then addressed some words in English to Worcester. And afterward the Count gave to my lady and mother to understand that the Queen his mistress had been waiting for an answer on two articles; the one concerning religion, and the other for an interview.

“In regard to what has occurred these latter days, that he must have seen how it happened by the fault of the chiefs of those who remained here; for when the late admiral was treacherously wounded at Notre Dame, he knew the affliction it threw us into — fearful that it might have occasioned great troubles in this kingdom — and the diligence we used to verify judicially whence it proceeded; and the verification was nearly finished, when they were so forgetful as to raise a conspiracy, to attempt the lives of myself, my lady and mother, and my brothers, and endanger the whole state; which was the cause that to avoid this I was compelled, to my very great regret, to permit what had happened in Paris; but as he had witnessed, I gave orders to stop, as soon as possible, this fury of the people, and place everyone on repose. On this, the Sieur Walsingham replied to my lady and mother that the exercise of the said religion had been interdicted in this kingdom. To which she also answered that this had not been done but for a good and holy purpose; namely, that the fury of the Catholic people might the sooner be allayed, who else had been reminded of the past calamities, and would again have been let loose against those of the said religion had they continued to preach in this kingdom. Also should these once more fix on any chiefs, which I will prevent as much as possible, giving him clearly and pointedly to understand that what is done here is much the same as what has been done and is now practiced by the Queen his mistress in her kingdom. For she permits the exercise but of one religion, although there are many of her people who are of another; and having also during her reign punished those of her subjects whom she found seditious and rebellious. It is true this has been done by the laws, but I, indeed, could not act in the same manner; for finding myself in such imminent peril, and the conspiracy raised against me and mine and my kingdom ready to be executed, I had no time to arraign and try in open justice as much as I wished, but was constrained, to my very great regret, to strike the blow lascher la main in what has been done in this city.”

This letter of Charles IX, however, does not here conclude. “My lady and mother” plainly acquaints the Earl of Worcester and Sir Francis Walsingham that her son had never interfered between their mistress and her subjects, and in return expects the same favor although, by accounts they had received from England, many ships were arming to assist their rebels at La Rochelle. “My lady and mother” advances another step, and declares that Elizabeth by treaty is bound to assist her son against his rebellious subjects; and they expect, at least, that Elizabeth will not only stop these armaments in all her ports, but exemplarily punish the offenders. I resume the letter.

“And on hearing this, the said Walsingham changed color, and appeared somewhat astonished, as my lady and mother well perceived by his face; and on this he requested the Count of Worcester to mention the order which he knew the Queen his mistress had issued to prevent these people from assisting those of La Rochelle; but that in England, so numerous were the seamen and others who gained their livelihood by maritime affairs, and who would starve without the entire freedom of the seas, that it was impossible to interdict them.”

Such is the first letter on English affairs which Charles IX dispatched to his ambassador, after an awful silence of six months, during which time La Motte Fenelon was not admitted into the presence of Elizabeth. The apology for the massacre of St. Bartholomew comes from the King himself, and contains several remarkable expressions, which are at least divested of that style of bigotry and exultation we might have expected: on the contrary, this sanguinary and inconsiderate young monarch, as he is represented, writes in a subdued and sorrowing tone, lamenting his hard necessity, regretting he could not have recourse to the laws, and appealing to others for his efforts to check the fury of the people, which he himself had let loose. Catherine de’ Medici, who had governed from the tender age of eleven years, when he ascended the throne, might unquestionably have persuaded him that a conspiracy was on the point of explosion. Charles IX died young, and his character is unfavorably viewed by the historians. In the voluminous correspondence which I have examined, could we judge by state letters of the character of him who subscribes them, we must form a very different notion; they are so prolix and so earnest that one might conceive they were dictated by the young monarch himself!

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on The St. Bartholomew Day Massacre by Henry White and Isaac Disraeli. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on St. Bartholomew Day Massacre diplomacy here and here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.