This series has nine easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: France’s King and Queen Ponder.

Introduction

In an age of ISIS after the 20th. century with its Nazis, Communists and Imperialists, it is difficult to understand the special horror that the Saint Bartholomew Day Massacre held in the Protestant world in the centuries on the 20th’s other side. After all, there were worse massacres in the rest of the world, some of them in Europe’s own colonial territories. This one occurred in the heart of Western Europe and reached the highest levels of its aristocracy.

The selections are from:

- The Massacre of Bartholomew by Henry White published in 1868.

- Curiosities of Literature by Isaac d’Israeli published in 1824.

For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. There’s seven and one-half installments by Henry White and one and one-half installments by Isaac d’Israeli.

Isaac Disraeli was the father of Benjamin Disraeli, the great Conservative Party leader and Prime Minister of Great Britain.

We begin with Henry White.

Time: 1572

Place: Paris

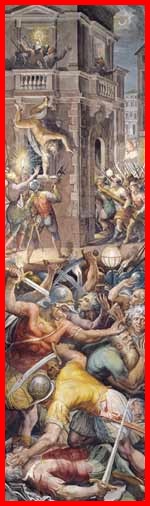

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The King sat moody and silent, biting his nails, as was his wont. He would come to no decision. He asked for proofs, and none was forthcoming, except some idle gossip of the streets and the foolish threats of a few hot-headed Huguenots. Charles had learned to love the admiral: could he believe that the gentle Coligny and that Rochefoucault, the companion of his rough sports, were guilty of this meditated plot? He desired to be the king of France — of Huguenots and Catholics alike — not a king of party. Catherine, in her despair, employed her last argument. She whispered in his ear, “Perhaps, sire, you are afraid.” As if struck by an arrow, he started from his chair. Raving like a madman, he bade them hold their tongues, and with fearful oaths exclaimed: “Kill the admiral, if you like, but kill all the Huguenots with him — all — all — all — so that not one be left to reproach me hereafter. See to it at once — at once; do you hear?” And he dashed furiously out of the closet, leaving the conspirators aghast at his violence.

But there was no time to be lost; the King might change his mind; the Huguenots might get wind of the plot. The murderous scheme must be carried out that very night, and accordingly the Duke of Guise was summoned to the Louvre. And now the different parts of the tragedy were arranged, Guise undertaking, on the strength of his popularity with the Parisian mob, to lead them to the work of blood. We may also imagine him begging as a favor the privilege of dispatching the admiral in retaliation for his father’s murder. The city was parted into districts, each of which was assigned to some trusty officer, Marshal Tavannes having the general superintendence of the military arrangements. The conspirators now separated, intending to meet again at ten o’clock. Guise went into the city, where he communicated his plans to such of the mob leaders as could be trusted. He told them of a bloody conspiracy among the Huguenot chiefs to destroy the King and the royal family and extirpate Catholicism; that a renewal of war was inevitable, but it was better that war should come in the streets of Paris than in the open field, for the leaders would thus be far more effectually punished and their followers crushed. He affirmed that letters had been intercepted in which the admiral had sought the aid of German reiters and Swiss pikemen, and that Montmorency was approaching with twenty-five thousand men to burn the city, as the Huguenots had often threatened. And, as if to give color to this idle story, a small body of cavalry had been seen from the walls in the early part of the day.

Such arguments and such falsehoods were admirably adapted to his hearers, who swore to carry out the Duke’s orders with secrecy and dispatch. “It is the will of our lord the King,” continued Henry of Guise, “that every good citizen should take up arms to purge the city of that rebel Coligny and his heretical followers. The signal will be given by the great bell of the Palace of Justice. Then let every true Catholic tie a white band on his arm and put a white cross in his cap, and begin the vengeance of God.” Finding upon inquiry that Le Charron, the provost of the merchants, was too weak and tender-hearted for the work before him, the Duke suggested that the municipality should temporarily confer his power on the ex-provost Marcel, a man of very different stamp.

About four in the afternoon Anjou rode through the crowded streets in company with his bastard brother Angoulome. He watched the aspect of the populace, and let fall a few insidious expressions in no degree calculated to quiet the turbulent passions of the citizens. One account says he distributed money, which is not probable, his afternoon ride being merely a sort of reconnaissance. The journals of the Hotel de Ville still attest the anxiety of the court — of Catherine and her fellow-conspirator — that the massacre should be sweeping and complete. “Very late in the evening” — it must have been after dark, for the King went to lie down at eight, and did not rise until ten — the provost was sent for. At the Louvre he found Charles, the Queen-mother, and the Duke of Anjou, with other princes and nobles, among whom we may safely include Guise, De Retz, and Tavannes. The King now repeated to him the story of the Huguenot plot which had already been whispered abroad by Guise of Anjou, and bade him shut the gates of the city, so that no one could pass in or out, and take possession of the keys. He was also to draw up all the boats on the river bank and chain them together, to remove the ferry, to muster under arms the able-bodied men of each ward under their proper officers, and hold them in readiness at the usual mustering-places to receive the orders of his majesty. The city artillery, which does not appear to have been as formidable as the word would imply, was to be stationed at the Grove to protect the Hotel de Ville or for any other duty required of it. With these instructions the provost returned to the Hotel de Ville, where he spent great part of the night in preparing the necessary orders, which were issued “very early the next morning.” There is reason for believing that these measures were simply precautions in case the Huguenots should resist and a bloody struggle should have to be fought in the streets of their capital. The municipality certainly took no part in the earlier massacres, whatever they may have done later. Tavannes complains of the “want of zeal” in some of the citizens, and Brantome admits that “it was necessary to threaten to hang some of the laggards.”

| Master List | Next—> |

More information the Saint Bartholomew Day Massacre here and here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.