This series has four easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: O’Neil Meets Elizabeth I.

Introduction

England had long tried to subjugate Ireland. After King Henry VIII started his own Protestant Church a new round of trouble began. Catholic Ireland versus Protestant England. When his daughter Elizabeth became Queen of England, one of the strongest monarchs in history, an ethnic and religious crackdown began.

This selection is from Ireland and Her Story by Justin McCarthy published in 1903. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Justin McCarthy (22 November 1830 – 24 April 1912) was an Irish nationalist and Liberal historian, novelist and politician.

Time: 1562

Place: Ireland

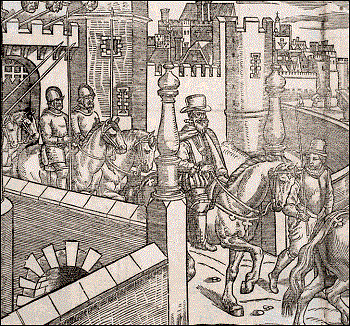

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

This time of trouble called forth some powerful champions of the Irish national cause. One of these, Shane O’Neil, has been celebrated in many a popular ballad. The head of the house to which he belonged had acknowledged allegiance to Henry VIII and received the title of Earl of Tyrone. The English title carried with it, according to English law, the principle of hereditary succession; but when the first earl died, the clan of O’Neil refused to adopt the English practice, and, according to the Irish principle of tanistry, chose as his successor the member of the house for whom they had the highest regard.

This was Shane O’Neil, who was a younger and not even a legitimate son of the Earl of Tyrone, but whose energy, courage, and strong national sentiments had already made him the hero of his sept. Shane O’Neil at once proclaimed himself the champion of Irish national independence. Queen Elizabeth, amid all her troubles with foreign states, had to pour large numbers of troops into Ireland, and these troops, as all historians admit, overran the country in the most reckless and merciless manner. Shane O’Neil, however, held his own, and began to prove himself a formidable opponent of English power.

The evidence of history leaves little or no doubt that Elizabeth connived at a plot for the removal of O’Neil by assassination. This project did not come to anything, and the Queen tried another policy. She was a woman not merely of high intellect but also of artistic feeling, and it would seem as if the picturesque figure of Shane O’Neil had aroused some interest in her. She proposed to enter into terms with the new “Lord of Ulster,” as he now declared himself, and invited him to visit her court in England. O’Neil seems to have accepted with great good-will this opportunity of seeing a life hitherto unknown to him, and he soon appeared at court. We read that O’Neil and his retainers presented themselves in their saffron-colored shirts and shaggy mantles, bearing battle-axes as their weapons, amid the stately gentlemen, the contemporaries of Essex and Raleigh, who thronged the court of the great Queen. A meeting took place on January 6, 1562.

Froude tells us the effect produced upon the court by the appearance of O’Neil and his followers: “The council, the peers, the foreign ambassadors, bishops, aldermen, dignitaries of all kinds, were present in state, as if at the exhibition of some wild animal of the desert. O’Neil stalked in, his saffron mantle sweeping round and round him, his hair curling on his back and clipped short below the eyes, which gleamed from under it with a gray lustre, frowning, fierce, and cruel. Behind him followed his gallow-glasses, bareheaded and fair-haired, with shirts of mail which reached beneath their knees, a wolf’s skin flung across their shoulders, and short, broad battle-axes in their hands.” O’Neil made a formal act of submission to the Queen, and negotiations set in for a definite and lasting arrangement. Nothing came of it. O’Neil seems to have understood that he was acting under a promise of safe-conduct, and was to be confirmed in the ownership of his estates in return for his submission. But, whatever may have been the misunderstanding, it is certain that these terms were not carried out according to O’Neil’s expectation. He was detained in London in qualified captivity, and was informed that he could only be restored to his lands when he had engaged to make war against his former allies the Scots, had pledged himself not to make war without the consent of the English government, and to set up no claim of supremacy over other chiefs in Ireland.

O’Neil seems to have proved himself skilful as a diplomatist, and he greatly gratified the Queen by paying intense deference to all her suggestions, and even by modestly requesting that she would choose a wife for him. He seems to have agreed to what he did not intend to carry out. Some terms were understood to be arranged at last, and on May 5, 1562, a royal proclamation was issued declaring that in future he was to be regarded as a good and loyal subject of the Queen. Shane returned to Ireland, and made known to his friends that the articles of agreement had been forced upon him under peril of captivity or death, and that he could not regard them as binding. He went so far to maintain the terms of the treaty as to begin a war against the Scots, and sent the Queen a list of his captives in token of his sincerity. But he still insisted that he had never made peace with the Queen except by her own seeking; that his ancestors were kings of Ulster, and that Ulster was his kingdom and should continue to be his.

He soon after applied to Charles IX, King of France, to send him five thousand men to assist him in expelling the English from Ireland. Then war set in again between the English Lord Deputy and Shane O’Neil. Defeated in many encounters, O’Neil again tried to make terms with the Queen, and again applied to the King of France for the help of an army to drive the English from Ireland and restore the Catholic faith. By this time the Scottish settlers in Ulster, who appear to have once been as much disliked by the English government as the Irish themselves, had turned completely against him. His end was not in keeping with his soldierly picturesque career. After a severe defeat he took refuge with some old tribal enemies of his, who at first professed to receive him as a friend and find a shelter for him. A quarrel sprang up at a drinking-festival during the June of 1567, and Shane and most of his companions were killed in the affray.

| Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.