As if the popular frenzy needed excitement, Marshal Tavannes, the military director of this deed of treachery, rode through the streets with dripping sword, shouting: “Kill! Kill! Bloodletting is as good in August as in May.”

Continuing The Saint Bartholomew Day Massacre,

with a selection The Massacre of Bartholomew by Henry White published in 1868. This selection is presented in 7.5 easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The St. Bartholomew Day Massacre. Today’s installment is by Henry White.

Time: 1572

Place: Paris

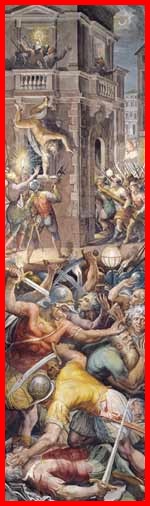

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

“I am not the man you take me for,” said the other, refusing the cloak. The Swiss plundered their victims as they fell, and, pointing to the heap of half-naked bodies, described them to the spectators as the men who had conspired to kill the King and all the royal family in their sleep, and make France a republic. But more disgraceful than even this massacre was the conduct of some of the ladies in Catherine’s train, of her “flying squadron,” who, later in the day, inspected and laughed at the corpses as they lay stripped in the court-yard, being especially curious about the body of Soubise, from whom his wife had sought to be divorced on the ground of nullity of marriage.

A few gentlemen succeeded in escaping from this slaughter. Margaret, “seeing it was daylight,” and imagining the danger past of which her sister had told her, fell asleep. But her slumbers were soon rudely broken.

“An hour later,” she continues, “I was awoke by a man knocking at the door and calling, ‘Navarre! Navarre!’ The nurse, thinking it was my husband, ran and opened it. It was a gentleman named LEran, who had received a sword-cut in the elbow and a spear-thrust in the arm; four soldiers were pursuing him, and they all rushed into my chamber after him. Wishing to save his life, he threw himself upon my bed. Finding myself clasped in his arms, I got out on the other side; he followed me, still clinging to me. I did not know the man, and could not tell whether he came to insult me or whether the soldiers were after him or me. We both shouted out, being equally frightened. At last, by God’s mercy, Captain de Nanay of the guards came in, and, seeing me in this condition, could not help laughing, although commiserating me. Severely reprimanding the soldiers for their indiscretion, he turned them out of the room, and granted me the life of the poor man who still clung to me. I made him lie down and had his wounds dressed in my closet until he was quite cured. While changing my night-dress, which was all covered with blood, the captain told me what had happened, and assured me that my husband was with the King and quite unharmed. He then conducted me to the room of my sister of Lorraine, which I reached more dead than alive. As I entered the anteroom, the doors of which were open, a gentleman named Bourse, running from the soldiers who pursued him, was pierced by a halberd three paces from me. I fell almost fainting into Captain de Nanay’s arms, imagining the same thrust had pierced us both. Being somewhat recovered, I entered the little room where my sister slept. While there De Moissans, my husband’s first gentleman, and Armagnac, his first valet-de-chambre, came and begged me to save their lives. I went and threw myself at the feet of the King and the Queen — my mother — to ask the favor, which they at last granted me.”

When Captain de Nanay arrived so opportunely, he was leaving the King’s chamber, whither he had conducted Henry of Navarre and the Prince of Conde. The tumult and excitement had worked Charles up to such a pitch of fury that the lives of the princes were hardly safe. But they were gentlemen, and their first words were to reproach the King for his breach of faith. Charles bade them be silent — “Messe ou mort” — (“Apostatize or die”). Henry demanded time to consider; while the Prince boldly declared that he would not change his religion: “With God’s help it is my intention to remain firm in my profession.” Charles, exasperated still more by this opposition to his will, angrily walked up and down the room, and swore that if they did not change in three days he would have their heads. They were then dismissed, but kept close prisoners within the palace.

The houses in which the Huguenots lodged, having been registered, were easily known. The soldiers burst into them, killing all they found, without regard to age or sex, and if any escaped to the roof they were shot down like pigeons. Daylight served to facilitate a work that was too foul even for the blackest midnight. Restraint of every kind was thrown aside, and while the men were the victims of bigoted fury, the women were exposed to violence unutterable. As if the popular frenzy needed excitement, Marshal Tavannes, the military director of this deed of treachery, rode through the streets with dripping sword, shouting: “Kill! Kill! Bloodletting is as good in August as in May.” One would charitably hope that this was the language of excitement, and that in his calmer moods he would have repented of his share in the massacre. But he was consistent to the last. On his death-bed he made a general confession of his sins, in which he did not mention the day of St. Bartholomew; and when his son expressed surprise at the omission, he observed, “I look upon that as a meritorious action, which ought to atone for all the sins of my life.”

The massacre soon exceeded the bounds upon which Charles and his mother had calculated. They were willing enough that the Huguenots should be murdered; but the murderers might not always be able to draw the line between orthodoxy and heresy. Things were fast getting beyond all control; the thirst for plunder was even keener than the thirst for blood. And it is certain that among the many ignoble motives by which Charles was induced to permit the massacre, was the hope of enriching himself and paying his debts out of the property of the murdered Huguenots. Nor were Anjou and others insensible to the charms of heretical property. Hence we find the provost of Paris remonstrating with the King about “the pillaging of the houses and the murders in the streets by the guards and others in the service of his majesty and the princes.” Charles, in reply, bade the magistrates “mount their horses, and with all the force of the city put an end to such irregularities, and remain on the watch day and night.”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.