Within the walls of the Louvre, within the hearing of Charles and his mother, if not actually within their sight, one of the foulest scenes of this detestable tragedy was enacted.

Continuing The Saint Bartholomew Day Massacre,

with a selection The Massacre of Bartholomew by Henry White published in 1868. This selection is presented in 7.5 easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The St. Bartholomew Day Massacre. Today’s installment is by Henry White.

Time: 1572

Place: Paris

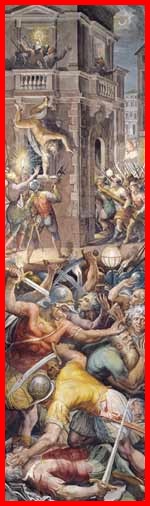

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

“Yes, it is he; I know him well,” said Guise, kicking the body as he spoke. “Well done, my men,” he continued, “we have made a good beginning. Forward — by the King’s command.” He mounted his horse and rode out of the court-yard, followed by Nevers, who cynically exclaimed as he looked at the body, “Sic transit gloria mundi.” Tosinghi took the chain of gold — the insignia of his office — from the admiral’s neck, and Petrucci, a gentleman in the train of the Duke of Nevers, cut off the head and carried it away carefully to the Louvre. Of all who were found in the house, not one was spared except Ambrose Pare, who was escorted in safety to the palace by a detachment of Anjou’s guard.

Coligny’s headless trunk was left for some hours where it fell, until it became the sport of rabble children, who dragged it all round Paris. They tried to burn it, but did little more than scorch and blacken the remains, which were first thrown into the river, and then taken out again “as unworthy to be food for fish,” says Claude Haton. In accordance with the old sentence of the Paris Parliament, it was dragged by the hangman to the common gallows at Montfaucon, and there hanged up by the heels. All the court went to gratify their eyes with the sight, and Charles, unconsciously imitating the language of Vitellius, said, as he drew near the offensive corpse, “The smell of a dead enemy is always sweet.” The body was left hanging for a fortnight or more, after which it was privily taken down by the admiral’s cousin, Marshal Montmorency, and it now rests, after many removals, in a wall among the ruins of his hereditary castle of Chatillon-sur-Loing. What became of the head no one knows.

When Guise left the admiral’s corpse lying in the court-yard, he went to the adjoining house, in which Teligny lived. All the inmates were killed, but he escaped by the roof. Twice he fell into the hands of the enemy, and twice he was spared; he perished at last by the sword of a man who knew not his amiable and inoffensive character. His neighbor La Rochefoucault was perhaps more fortunate in his fate. He had hardly fallen asleep when he was disturbed by the noise in the street. He heard shouts and the sound of many footsteps; and scarcely awake and utterly unsuspicious, he went to his bedroom door at the first summons in the King’s name. He seems to have thought that Charles, indulging in one of his usual mad frolics, had come to punish him as he had punished others, like schoolboys. He opened the door and fell dead across the threshold, pierced by a dozen weapons.

When the messenger returned from the Duke of Guise with the answer that it was “too late,” Catherine, fearing that such disobedience to the royal commands might incense the King and awaken him to a sense of all the horrors that were about to be perpetrated in his name, privately gave orders to anticipate the hour. Instead of waiting until the matin bell should ring out from the old clock tower of the Palace of Justice, she directed the signal to be given from the nearer belfry of St. Germain l’Auxerrois. As the harsh sound rang through the air of that warm summer night, it was caught up and echoed from tower to tower, rousing all Paris from their slumbers.

Immediately from every quarter of that ancient city uprose a tumult as of hell. The clanging of bells, the crashing doors, the rush of armed men, the musket-shots, the shrieks of their victims, and high over all the yells of the mob, fiercer and more pitiless than hungry wolves — made such an uproar that the stoutest hearts shrank appalled, and the sanest appear to have lost their reason. Women unsexed, men wanting but the strength of the wild beast, children without a single charm of youth or innocence, crowded the streets where rising day still struggled with the glare of a thousand torches. They smelt the odor of blood, and, thirsting to indulge their passions for once with impunity, committed horrors that have become the marvel of history.

Within the walls of the Louvre, within the hearing of Charles and his mother, if not actually within their sight, one of the foulest scenes of this detestable tragedy was enacted. At daybreak, says Queen Margaret of Navarre, her husband rose to go and play tennis, with a determination to be present at the King’s lever, and demand justice for the assault on the admiral. He left his apartment, accompanied by the Huguenot gentlemen who had kept watch around him during the night. At the foot of the stairs he was arrested, while the gentlemen with him were disarmed, apparently without any attempt at resistance. A list of them had been carefully drawn up, which the sire D’O, quartermaster of the guards, read out. As each man answered his name, he stepped into the court-yard, where he had to make his way through a double line of Swiss mercenaries. Sword, spear, and halberd made short work of them, and two hundred, according to Davila, of the best blood of France soon lay a ghastly pile beneath the windows of the palace. Charles, it is said, looked on coldly at the horrid deed, the victims appealing in vain to his mercy. Among the gentlemen they murdered were two who had been boldest in their language to the King not many hours before — Segur, Baron of Pardaillan, and Armand de Clermont, Baron of Pilles, who with stentorian voices called upon the King to be true to his word. De Pilles took off his rich cloak and offered it to someone whom he recognized: “Here is a present from the hand of De Pilles, basely and traitorously murdered.”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.