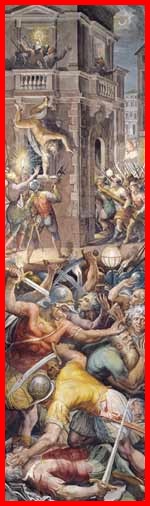

The St. Bartholomew Day Massacre began on Sunday and lasted through Tuesday.

Continuing The Saint Bartholomew Day Massacre,

with a selection The Massacre of Bartholomew by Henry White published in 1868. This selection is presented in 7.5 easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The St. Bartholomew Day Massacre. Today’s installment is by Henry White.

Time: 1572

Place: Paris

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Another proclamation, countersigned by Nevers, was issued about five in the afternoon, commanding the people to lay down the arms which they had taken up “that day by the King’s orders,” and to leave the streets to the soldiers only — as if implying that they alone were to kill and plunder.

The massacre, commenced on Sunday, was continued through that and the two following days. Capilupi tells us, with wonderful simplicity, “that it was a holiday, and therefore the people could more conveniently find leisure to kill and plunder.” It is impossible to assign to each day its task of blood; in all but a few exceptional cases, we know merely that the victims perished in the general slaughter. Writing in the midst of the carnage, probably not later than noon on the 24th, the nuncio Salviati says:

“The whole city is in arms; the houses of the Huguenots have been forced with great loss of life, and sacked by the populace with incredible avidity. Many a man to-night will have his horses and his carriage, and will eat and drink off plate, who had never dreamed of it in his life before. In order that matters may not go too far, and to prevent the revolting disorders occasioned by the insolence of the mob, a proclamation has just been issued, declaring that there shall be three hours in the day during which it shall be unlawful to rob and kill; and the order is observed, though not universally. You can see nothing in the streets but white crosses in the hats and caps of everyone you meet, which has a fine effect!”

The nuncio says nothing of the streets encumbered with bleeding corpses, nothing of the cart-loads of bodies conveyed to the Seine, and then flung into the river, “so that not only were all the waters in it turned to blood, but so many corpses grounded on the bank of the little island of Louvre that the air became infected with the smell of corruption.” The living, tied hand and foot, were thrown off the bridges. One man — probably a rag-gatherer — brought two little children in his creel, and tossed them into the water as carelessly as if they had been blind kittens. An infant, yet unable to walk, had a cord tied round its neck, and was dragged through the streets by a troop of children nine or ten years old. Another played with the beard and smiled in the face of the man who carried him; but the innocent caress exasperated instead of softened the ruffian, who stabbed the child, and with an oath threw it into the Seine. Among the earliest victims was the wife of the King’s plumassier. The murderers broke into her house on the Notre-Dame bridge, about four in the morning, stabbed her, and flung her still breathing into the river. She clung for some time to the wooden piles of the bridge, and was killed at last with stones, her body remaining for four days entangled by her long hair among the woodwork. The story goes that her husband’s corpse, being thrown over, fell against hers and set it free, both floating away together down the stream. Madeleine Briconnet, the widow of Theobald of Yverni, disguised herself as a woman of the people, so that she might save her life, but was betrayed by the fine petticoat which hung below her coarse gown. As she would not recant, she was allowed a few moments’ prayer, and then tossed into the water. Her son-in-law, the marquis Renel, escaping in his shirt, was chased by the murderers to the bank of the river, where he succeeded in unfastening a boat. He would have got away altogether but for his cousin Bussy d’Amboise, who shot him down with a pistol. One Keny, who had been stabbed and flung into the Seine, was revived by the reaction of the cold water. Feeble as he was he swam to a boat and clung to it, but was quickly pursued. One hand was soon cut off with a hatchet, and as he still continued to steer the boat down the stream, he was “quieted” by a musket-shot. One Puviaut, or Pluviaut, who met with a similar fate, became the subject of a ballad.

Captain Moneins had been put into a safe hiding-place by his friend Fervacques, who went and begged the King to spare the life of the fugitive. Charles not only refused, but ordered him to kill Moneins if he desired to save his own life. Fervacques would not stain his own hands, but made his friend’s hiding-place known.

Brion, governor of the young Marquis of Conti, the Prince of Condes brother, snatched the child from his bed, and, without stopping to dress him, was hurrying away to a place of safety, when the boy was torn from his arms, and he himself murdered before the eyes of his pupil. We are told that the child “cried and begged they would save his tutor’s life.”

The houses on the bridge of Notre-Dame, inhabited principally by Protestants, were witnesses to many a scene of cruelty. All the inmates of one house were massacred, except a little girl, who was dipped stark naked in the blood of her father and mother and threatened to be served like them if she turned Huguenot. The Protestant booksellers and printers were particularly sought after. Spire Niquet was burned over a slow fire made out of his own books, and thrown lifeless, but not dead, into the river. Oudin Petit fell a victim to the covetousness of his son-in-law, who was a Catholic bookseller. Rene Bianchi, the Queen’s perfumer, is reported to have killed with his own hands a young man, a cripple, who had already displayed much skill in goldsmith’s work. This is the only man whose death the King lamented, “because of his excellent workmanship, for his shop was entirely stripped.”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.