When King James succeeded to the throne he promised the Irish that they should have the right of practicing their religion, at least in private; but he soon recalled his promise.

Today’s installment concludes «SERIESNAME»,

our selection from Ireland and Her Story by Justin McCarthy published in 1903.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of four thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Earls Flee Ireland.

Time: 1603

Place: Ireland

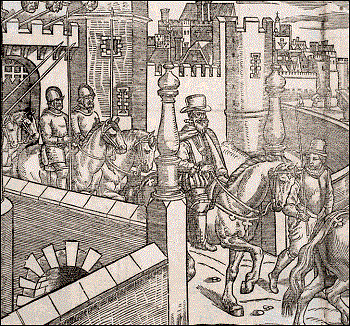

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

When Tyrone returned to his own country he found that the reign of peace and reconciliation between England and Ireland was as far off as ever. Tyrone had believed it was fortunate for him to have made terms of peace in King James’ reign and not in Elizabeth’s. But he soon found that his hopes of a better time coming were premature. James no doubt thought it good policy to secure the allegiance of a man like Tyrone by apparently generous concessions. But he had no idea of adopting any policy toward Ireland other than the old familiar policy of striving to reduce her to the conditions of an English province, with English laws, customs, costumes, and religion.

The King appears to have set his mind on the complete suppression of the national religion by the enforcement of the sternest penal laws against Catholics. He was determined also to blot out whatever remained of the old Brehon laws, still dear to the memories of the people, and still cherished among the sacred traditions of the country. When King James succeeded to the throne he promised the Irish that they should have the right of practicing their religion, at least in private; but he soon recalled his promise, and made it clear that those who would retain the protection of the new ruling system must abjure the faith of their fathers. Those who were put into the actual government of the country saw that this policy could not be carried out without much resistance, and therefore decreed the complete disarmament of all Irish retainers who still acknowledged the leadership of the chieftains. One of the greatest of these chieftains, O’Donnell, Earl of Tyrconnel, was called upon to conform openly to the English Church, under pain of being proceeded against as a traitor.

The state of things he found existing on his return to Ireland would naturally have driven Tyrone into rebellion, and the rulers of the country appear to have made up their minds that he must be planning some such rising. Tyrconnel was naturally regarded as an enemy of the same order, and the policy of the ruling powers was to anticipate their designs and condemn them in advance. Tyrone and Tyrconnel were accordingly proclaimed traitors to the King. The two earls determined that, as immediate insurrection had no chance of success, there was no safety for them but in prompt escape from the country.

Then followed “the flight of the earls.” Tyrone and Tyrconnel, with their families and many of their friends and retainers, nearly a hundred persons in all, made their escape in one vessel from the Irish shore, and for twenty-one days were at the mercy of the sea and of the equinoctial winds, for they sailed about the middle of September. A story characteristic of the faith which then filled the hearts of Irish chieftains is told. Tyrone fastened his golden crucifix to a string and drew it through the sea at the stern of the vessel, in the hope that the waves might thus be stilled. In the first week of October they landed on the shore of France and travelled on to Rouen, receiving nothing but kindness from the French. When King James heard of their flight he at once demanded from France the surrender of the earls, but Henry IV refused to surrender them.

Henry received the exiles with gracious and friendly greeting, but it was not thought prudent by the earls, any more than by the French King, they should remain in France at the risk of involving the two countries in war. The earls, with their families and followers, went into Flanders and then on to Rome. Pope Paul V gave them a cordial welcome, and made liberal arrangements for their maintenance, while the King of Spain showed his traditional sympathy with Ireland by settling pensions on them. Tyrconnel died soon after, in the Franciscan Church of St. Pietro di Montorio, and was laid in his grave wrapped in the robe of a Franciscan friar. Tyrone lived for several years. He was filled in this later time by a passionate longing to see once more the loved country of his birth, and he appealed to the English government for permission to return to Ireland and live quietly there until the end came. His request was not granted. The English authorities, no doubt, felt good reason to believe that his return to Ireland would be the cause of profound and dangerous emotion among the people who loved him and whom he loved so well.

His later years in Rome were literally darkened, because his sight, which had been for some time failing, soon left him to absolute blindness. He died on July 20, 1616, having lived a life of seventy-six years. Tyrone’s body was laid to rest in the same church which held the body of his comrade Tyrconnel. Their graves are side by side. A modern writer tells us that the church which has become the tomb of the two exiled earls stands “where the Janiculum overlooks the glory of Rome, the yellow Tiber and the Alban Hills, the deathless Coliseum, and the stretching Campagna.” “Raphael had painted his Transfiguration for the grand altar; the hand of Sebastiano del Piombo had colored the walls with the scourging of the Redeemer.” The present writer has seen the graves, and even the merest stranger to the spirit of Irish history must feel impressed by the story of the two exiles who found their last resting-place enclosed by such a scene.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Earls Flee Ireland by Justin McCarthy from his book Ireland and Her Story published in 1903. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.