Before long the greater part of Ireland was in the hands of the Irish forces. Hugh O’Neil was the Earl of Tyrone.

Continuing Earls Flee Ireland,

our selection from Ireland and Her Story by Justin McCarthy published in 1903. The selection is presented in four easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Earls Flee Ireland.

Time: 1603

Place: Ireland

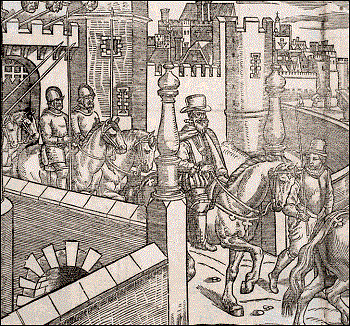

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

One of the most important and famous struggles made during these years against English dominion was led by Hugh O’Neil. This celebrated Irish leader was the grandson of that Shane O’Neil whom Henry VIII had created Earl of Tyrone. He had led thus far a very different life from that usually led by an Irish chieftain. The ruling powers were at first inclined to make a favorite of him, and confirmed him in his earldom and estates. He was brought over when very young to England, and we learn that even in the brilliant court of Queen Elizabeth he was distinguished for gifts and graces of body and mind. For a long time Tyrone seemed a loyal supporter of English rule. He commanded a troop in the Queen’s service, and even took part in the suppression of risings in his own country, cooperating with the Earl of Essex in the Ulster wars and the settlement of Antrim. One romantic incident of his life brought him into personal antagonism with Sir Henry Bagnal, the Lord Marshal of Ireland. Hugh O’Neil had been left a widower, and he fell in love with Bagnal’s beautiful sister. Bagnal highly disapproved of the match, but, as the lady was heart and soul in love with the Irish chieftain, her brother’s opposition was vain. She eloped with her lover and married him. Bagnal became O’Neil’s determined enemy. It may be that Sir Henry Bagnal did his best to prejudice the ruling authorities against O’Neil, and at that time no very substantial evidence was needed to set up a charge of treason against an Irish chieftain.

Perhaps when O’Neil returned to his own country he was recalled to national sentiments by the sight of oppression there, and it is certain that he was roused to indignation by the arbitrary imprisonment of one of his kinsmen known as Red Hugh. When Red Hugh succeeded in escaping from prison he inspired Tyrone with a keen sense of his wrongs, and brought him into the temper of insurrection. O’Neil threw himself completely into the new movement for independence. A confederation of Irish chieftains was organized, and O’Neil took the command. He proved himself possessed of the most genuine military talents, and he could play the part of the statesman as well as of the soldier. The confederation of Irish chieftains soon became an embattled army, and the brothers-in-law met in arms as hostile commanders on the shores of the northern Blackwater. As one historian has well remarked, there was something positively Homeric about this struggle, in which the two men connected by marriage encountered each other as commanders of opposing armies. Events had been moving on since the marriage between Tyrone and Bagnal’s sister. O’Neil’s young wife had found her early grave before this last engagement between her husband and her brother. The army of Bagnal was completely defeated, and Bagnal was killed upon the field.

For a time victory seemed to follow Tyrone. Before long the greater part of Ireland was in the hands of the Irish forces. The Earl of Essex was sent to Ireland at the head of the largest army ever dispatched from England for the conquest of the island. But Essex does not seem to have made any serious effort. He appears to have had some idea of coming to terms with Tyrone. The two had a meeting, over which many pages of historical description and conjecture have been spent, but it is certain that, so far as Essex was concerned, neither peace nor war came of his intervention. He was recalled to London. His failure in Ireland, and the trouble it brought upon him in England, only drove him into the wild movements which led to his condemnation as a traitor and to his death on the scaffold.

The place which Essex had so unsuccessfully endeavored to hold was given to Lord Mountjoy, who proved himself a more fitting man for the work. Mountjoy was a strong man, who made up his mind from the first that he was sent to Ireland to fight the Irish. He had a great encounter with Tyrone, and Tyrone was defeated. From that moment the fortunes of the struggle seem to have turned. The resources of the Irish were very limited, and it was almost certain that, if the English government carried on the war long enough, the Irish must sooner or later be defeated. It was a question of numbers and weapons and money, and in all these the English had an immense superiority. Tyrone had great hopes that a Spanish army would come to the aid of the Irish. A large Spanish force was actually dispatched for the purpose, but the news of Tyrone’s defeat reached the Spaniards on their arrival, and they promptly reembarked, and gave up what they considered a lost cause. Some of the Irish chiefs were compelled to surrender; others fled to Spain, in the hope of stirring up some movement there against England, or at least of finding a place of shelter. Ireland was suffering almost everywhere from famine, and in many districts famine of the most ghastly order. Tyrone found it impossible to carry on the struggle for independence under such terrible conditions. There was nothing for it but to surrender and come to terms as best he could with his conquering enemy.

The times just then might have been regarded as peculiarly favorable for Tyrone. Queen Elizabeth was dead, and the son of Mary Stuart sat on the English throne. Tyrone made a complete surrender of his estates, pledged himself to enter into alliance with no foreign power against England, and even undertook to promote the introduction of English laws and customs into any part of Ireland over which he had influence. In return Tyrone received from the King the restoration of his lands and his title by letters-patent, and a free pardon for his campaigns against England. He was brought to London to be presented to King James, and was treated with great courtesy and hospitality. This aroused much anger among some of the older soldiers and courtiers in London, who did not understand why an Irish rebel should be treated as if he were a respectable member of society. Sir John Harrington expressed his opinions very freely in letters which are still preserved. “I have lived,” he wrote, “to see that damnable rebel Tyrone brought to England, honored, and well liked. Oh! what is there that does not prove the inconstancy of worldly matters? I adventured perils by sea and land, was near starving, ate horseflesh in Munster, and all to quell that man, who now smileth in peace at those who did harass their lives to destroy him; and now doth Tyrone dare us, old commanders, with his presence and protection.”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.