By the Indian standard, it was a mighty nation; yet the entire Huron population did not exceed that of a third or fourth class American city. In the age-old Hurons versus Iroquois conflict, the Hurons were the weaker power.

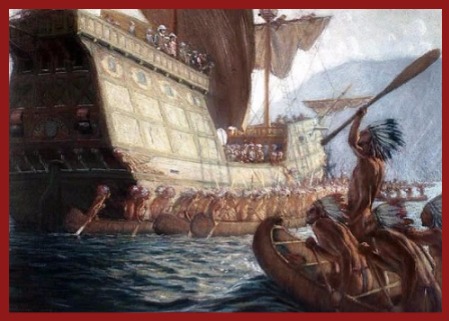

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously on Parkman

Before him [Champlain – jl], too far for sight, lay the spirit-haunted Manitonalins, and, southward, spread the vast bosom of the Georgian Bay. For more than a hundred miles, his course was along its eastern shores, among islets countless as the sea-sands, — an archipelago of rocks worn for ages by the wash of waves. He crossed Byng Inlet, Franklin Inlet, Parry Sound, and the wider bay of Matchedash, and seems to have landed at the inlet now called Thunder Bay, at the entrance of the Bay of Matchedash, and a little west of the Harbor of Penetanguishine.

An Indian trail led inland, through woods and thickets, across broad meadows, over brooks, and along the skirts of green acclivities. To the eye of Champlain, accustomed to the desolation he had left behind, it seemed a land of beauty and abundance. He reached at last a broad opening in the forest, with fields of maize, pumpkins ripening in the sun, patches of sunflowers, from the seeds of which the Indians made hair-oil, and, in the midst, the Huron town of Otonacha. In all essential points, it resembled that which Cartier, eighty years before, had seen at Montreal, — the same triple palisade of crossed and intersecting trunks, and the same long lodges of bark, each containing several families. Here, within an area of thirty or forty miles, was the seat of one of the most remarkable savage communities on the continent. By the Indian standard, it was a mighty nation; yet the entire Huron population did not exceed that of a third or fourth class American city.

To the south and southeast lay other tribes of kindred race and tongue, all stationary, all tillers of the soil, and all in a state of social advancement when compared with the roving bands of Eastern Canada: the Neutral Nation west of the Niagara, and the Eries and Andastes in Western New York and Pennsylvania; while from the Genesee eastward to the Hudson lay the banded tribes of the Iroquois, leading members of this potent family, deadly foes of their kindred, and at last their destroyers.

In Champlain the Hurons saw the champion who was to lead them to victory. There was bountiful feasting in his honor in the great lodge at Otonacha; and other welcome, too, was tendered, of which the Hurons were ever liberal, but which, with all courtesy, was declined by the virtuous Champlain. Next, he went to Carmaron, a league distant, and then to Tonagnainchain and Tequenonquihayc; till at length he reached Carhagouha, with its triple palisade thirty-five feet high. Here he found Le Caron. The Indians, eager to do him honor, were building for him a bark lodge in the neighboring forest, fashioned like their own, but much smaller. In it the friar made an altar, garnished with those indispensable decorations which he had brought with him through all the vicissitudes of his painful journeying; and hither, night and day, came a curious multitude to listen to his annunciation of the new doctrine. It was a joyful hour when he saw Champlain approach his hermitage; and the two men embraced like brothers long sundered.

The twelfth of August was a day evermore marked with white in the friar’s calendar. Arrayed in priestly vestments, he stood before his simple altar; behind him his little band of Christians, — the twelve Frenchmen who had attended him, and the two who had followed Champlain. Here stood their devout and valiant chief, and, at his side, that pioneer of pioneers, Etienne Brule the interpreter. The Host was raised aloft; the worshippers kneeled. Then their rough voices joined in the hymn of praise, Te Deum laudamus; and then a volley of their guns proclaimed the triumph of the faith to the okies, the manitous, and all the brood of anomalous devils who had reigned with undisputed sway in these wild realms of darkness. The brave friar, a true soldier of the Church, had led her forlorn hope into the fastnesses of hell; and now, with contented heart, he might depart in peace, for he had said the first mass in the country of the Hurons.

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

1615, 1616 THE GREAT WAR PARTY

The lot of the favored guest of an Indian camp or village is idleness without repose, for he is never left alone, with the repletion of incessant and inevitable feasts. Tired of this inane routine, Champlain, with some of his Frenchmen, set forth on a tour of observation. Journeying at their ease by the Indian trails, they visited, in three days, five palisaded villages. The country delighted them, with its meadows, its deep woods, its pine and cedar thickets, full of hares and partridges, its wild grapes and plums, cherries, crab-apples, nuts, and raspberries. It was the seventeenth of August when they reached the Huron metropolis, Cahiague, in the modern township of Orillia, three leagues west of the river Severn, by which Lake Simcoe pours its waters into the bay of Matchedash. A shrill clamor of rejoicing, the fixed stare of wondering squaws, and the screaming flight of terrified children hailed the arrival of Champlain. By his estimate, the place contained two hundred lodges; but they must have been relatively small, since, had they been of the enormous capacity sometimes found in these structures, Cahiague alone would have held the whole Huron population. Here was the chief rendezvous, and the town swarmed with gathering warriors. There was cheering news; for an allied nation, called Carantonans, probably identical with the Andastes, had promised to join the Hurons in the enemy’s country, with five hundred men. Feasts and the war-dance consumed the days, till at length the tardy bands had all arrived; and, shouldering their canoes and scanty baggage, the naked host set forth.

At the outlet of Lake Simcoe they all stopped to fish, — their simple substitute for a commissariat. Hence, too, the intrepid Etienne Brule, at his own request, was sent with twelve Indians to hasten forward the five hundred allied warriors, — a dangerous venture, since his course must lie through the borders of the Iroquois.

He set out on the eighth of September, and on the morning of the tenth, Champlain, shivering in his blanket, awoke to see the meadows sparkling with an early frost, soon to vanish under the bright autumnal sun. The Huron fleet pursued its course along Lake Simcoe, across the portage to Balsam or Sturgeon Lake, and down the chain of lakes which form the sources of the river Trent. As the long line of canoes moved on its way, no human life was seen, no sign of friend or foe; yet at times, to the fancy of Champlain, the borders of the stream seemed decked with groves and shrubbery by the hands of man, and the walnut trees, laced with grape-vines, seemed decorations of a pleasure-ground.

They stopped and encamped for a deer-hunt. Five hundred Indians, in line, like the skirmishers of an army advancing to battle, drove the game to the end of a woody point; and the canoe-men killed them with spears and arrows as they took to the river. Champlain and his men keenly relished the sport, but paid a heavy price for their pleasure. A Frenchman, firing at a buck, brought down an Indian, and there was need of liberal gifts to console the sufferer and his friends.

The canoes now issued from the mouth of the Trent. Like a flock of venturous wild-fowl, they put boldly out upon Lake Ontario, crossed it in safety, and landed within the borders of New York, on or near the point of land west of Hungry Bay. After hiding their light craft in the woods, the warriors took up their swift and wary march, filing in silence between the woods and the lake, for four leagues along the strand. Then they struck inland, threaded the forest, crossed the outlet of Lake Oneida, and after a march of four days, were deep within the limits of the Iroquois. On the ninth of October some of their scouts met a fishing-party of this people, and captured them, — eleven in number, men, women, and children. They were brought to the camp of the exultant Hurons. As a beginning of the jubilation, a chief cut off a finger of one of the women, but desisted from further torturing on the angry protest of Champlain, reserving that pleasure for a more convenient season.

On the next day they reached an open space in the forest. The hostile town was close at hand, surrounded by rugged fields with a slovenly and savage cultivation. The young Hurons in advance saw the Iroquois at work among the pumpkins and maize, gathering their rustling harvest. Nothing could restrain the hare-brained and ungoverned crew. They screamed their war-cry and rushed in; but the Iroquois snatched their weapons, killed and wounded five or six of the assailants, and drove back the rest discomfited. Champlain and his Frenchmen were forced to interpose; and the report of their pieces from the border of the woods stopped the pursuing enemy, who withdrew to their defences, bearing with them their dead and wounded.

It appears to have been a fortified town of the Onondagas, the central tribe of the Iroquois confederacy, standing, there is some reason to believe, within the limits of Madison County, a few miles south of Lake Oneida. Champlain describes its defensive works as much stronger than those of the Huron villages. They consisted of four concentric rows of palisades, formed of trunks of trees, thirty feet high, set aslant in the earth, and intersecting each other near the top, where they supported a kind of gallery, well defended by shot-proof timber, and furnished with wooden gutters for quenching fire. A pond or lake, which washed one side of the palisade, and was led by sluices within the town, gave an ample supply of water, while the galleries were well provided with magazines of stones.

Champlain was greatly exasperated at the desultory and futile procedure of his Huron allies. Against his advice, they now withdrew to the distance of a cannon-shot from the fort, and encamped in the forest, out of sight of the enemy. “I was moved,” he says, “to speak to them roughly and harshly enough, in order to incite them to do their duty; for I foresaw that if things went according to their fancy, nothing but harm could come of it, to their loss and ruin. He proceeded, therefore, to instruct them in the art of war.”

In the morning, aided doubtless by his ten or twelve Frenchmen, they set themselves with alacrity to their prescribed task. A wooden tower was made, high enough to overlook the palisade, and large enough to shelter four or five marksmen. Huge wooden shields, or movable parapets, like the mantelets of the Middle Ages, were also constructed. Four hours sufficed to finish the work, and then the assault began. Two hundred of the strongest warriors dragged the tower forward, and planted it within a pike’s length of the palisade. Three arquebusiers mounted to the top, where, themselves well sheltered, they opened a raking fire along the galleries, now thronged with wild and naked defenders. But nothing could restrain the ungovernable Hurons. They abandoned their mantelets, and, deaf to every command, swarmed out like bees upon the open field, leaped, shouted, shrieked their war-cries, and shot off their arrows; while the Iroquois, yelling defiance from their ramparts, sent back a shower of stones and arrows in reply. A Huron, bolder than the rest, ran forward with firebrands to burn the palisade, and others followed with wood to feed the flame. But it was stupidly kindled on the leeward side, without the protecting shields designed to cover it; and torrents of water, poured down from the gutters above, quickly extinguished it. The confusion was redoubled. Champlain strove in vain to restore order. Each warrior was yelling at the top of his throat, and his voice was drowned in the outrageous din. Thinking, as he says, that his head would split with shouting, he gave over the attempt, and busied himself and his men with picking off the Iroquois along their ramparts.

The attack lasted three hours, when the assailants fell back to their fortified camp, with seventeen warriors wounded. Champlain, too, had received an arrow in the knee, and another in the leg, which, for the time, disabled him. He was urgent, however, to renew the attack; while the Hurons, crestfallen and disheartened, refused to move from their camp unless the five hundred allies, for some time expected, should appear.

– Pioneers of France in the New World Part II, Chapter 14 by Francis Parkman

Champlain’s intervention did not decisively change the balance of power between the Hurons versus Iroquois.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Introduction.

If, at times, it may seem that range has been allowed to fancy, it is so in appearance only; since the minutest details of narrative or description rest on authentic documents or on personal observation.

Faithfulness to the truth of history involves far more than a research, however patient and scrupulous, into special facts. Such facts may be detailed with the most minute exactness, and yet the narrative, taken as a whole, may be unmeaning or untrue. The narrator must seek to imbue himself with the life and spirit of the time. He must study events in their bearings near and remote; in the character, habits, and manners of those who took part in them, he must himself be, as it were, a sharer or a spectator of the action he describes.

With respect to that special research which, if inadequate, is still in the most emphatic sense indispensable, it has been the writer’s aim to exhaust the existing material of every subject treated. While it would be folly to claim success in such an attempt, he has reason to hope that, so far at least as relates to the present volume, nothing of much importance has escaped him. With respect to the general preparation just alluded to, he has long been too fond of his theme to neglect any means within his reach of making his conception of it distinct and true.

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

Here is a Kindle version: Complete Works for just $2.

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Biography of Samuel de Champlain.

- Article on New France in North America.

- From the Canada History Project.

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.