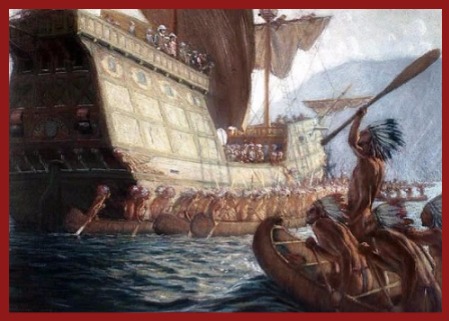

As we turn the ancient, worm-eaten page which preserves the simple record of his fortunes, a wild and dreary scene rises before the mind . . . . Explorers Indians, together.

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously on Parkman

They waited five days in vain, beguiling the interval with frequent skirmishes, in which they were always worsted; then began hastily to retreat, carrying their wounded in the centre, while the Iroquois, sallying from their stronghold, showered arrows on their flanks and rear. The wounded, Champlain among the rest, after being packed in baskets made on the spot, were carried each on the back of a strong warrior, “bundled in a heap,” says Champlain, “doubled and strapped together after such a fashion that one could move no more than an infant in swaddling-clothes. The pain is extreme, as I can truly say from experience, having been carried several days in this way, since I could not stand, chiefly on account of the arrow-wound I had got in the knee. I never was in such torment in my life, for the pain of the wound was nothing to that of being bound and pinioned on the back of one of our savages. I lost patience, and as soon as I could bear my weight I got out of this prison, or rather out of hell.”

At length the dismal march was ended. They reached the spot where their canoes were hidden, found them untouched, embarked, and recrossed to the northern shore of Lake Ontario. The Hurons had promised Champlain an escort to Quebec; but as the chiefs had little power, in peace or war, beyond that of persuasion, each warrior found good reasons for refusing to lend his canoe. Champlain, too, had lost prestige. The “man with the iron breast” had proved not inseparably wedded to victory; and though the fault was their own, yet not the less was the lustre of their hero tarnished. There was no alternative. He must winter with the Hurons. The great war party broke into fragments, each band betaking itself to its hunting-ground. A chief named Durantal, or Darontal, offered Champlain the shelter of his lodge, and he was glad to accept it.

Meanwhile, Etienne Brule had found cause to rue the hour when he undertook his hazardous mission to the Carantonan allies. Three years passed before Champlain saw him. It was in the summer of 1618, that, reaching the Saut St. Louis, he there found the interpreter, his hands and his swarthy face marked with traces of the ordeal he had passed. Brule then told him his story.

He had gone, as already mentioned, with twelve Indians, to hasten the march of the allies, who were to join the Hurons before the hostile town. Crossing Lake Ontario, the party pushed onward with all speed, avoiding trails, threading the thickest forests and darkest swamps, for it was the land of the fierce and watchful Iroquois. They were well advanced on their way when they saw a small party of them crossing a meadow, set upon them, surprised them, killed four, and took two prisoners, whom they led to Carantonan, — a palisaded town with a population of eight hundred warriors, or about four thousand souls. The dwellings and defenses were like those of the Hurons, and the town seems to have stood on or near the upper waters of the Susquehanna. They were welcomed with feasts, dances, and an uproar of rejoicing. The five hundred warriors prepared to depart; but, engrossed by the general festivity, they prepared so slowly, that, though the hostile town was but three days distant, they found on reaching it that the besiegers were gone. Brule now returned with them to Carantonan, and, with enterprise worthy of his commander, spent the winter in a tour of exploration. Descending a river, evidently the Susquehanna, he followed it to its junction with the sea, through territories of populous tribes, at war the one with the other. When, in the spring, he returned to Carantonan, five or six of the Indians offered to guide him towards his countrymen. Less fortunate than before, he encountered on the way a band of Iroquois, who, rushing upon the party, scattered them through the woods. Brule ran like the rest. The cries of pursuers and pursued died away in the distance. The forest was silent around him. He was lost in the shady labyrinth. For three or four days he wandered, helpless and famished, till at length he found an Indian foot-path, and, choosing between starvation and the Iroquois, desperately followed it to throw himself on their mercy. He soon saw three Indians in the distance, laden with fish newly caught, and called to them in the Huron tongue, which was radically similar to that of the Iroquois. They stood amazed, then turned to fly; but Brule, gaunt with famine, flung down his weapons in token of friendship. They now drew near, listened to the story of his distress, lighted their pipes, and smoked with him; then guided him to their village, and gave him food.

A crowd gathered about him. “Whence do you come? Are you not one of the Frenchmen, the men of iron, who make war on us?”

Brule answered that he was of a nation better than the French, and fast friends of the Iroquois.

His incredulous captors tied him to a tree, tore out his beard by handfuls, and burned him with fire-brands, while their chief vainly interposed in his behalf. He was a good Catholic, and wore an Agnus Dei at his breast. One of his torturers asked what it was, and thrust out his hand to take it.

“If you touch it,” exclaimed Brule, “you and all your race will die.”

The Indian persisted. The day was hot, and one of those thunder-gusts which often succeed the fierce heats of an American midsummer was rising against the sky. Brule pointed to the inky clouds as tokens of the anger of his God. The storm broke, and, as the celestial artillery boomed over their darkening forests, the Iroquois were stricken with a superstitious terror. They all fled from the spot, leaving their victim still bound fast, until the chief who had endeavored to protect him returned, cut the cords, led him to his lodge, and dressed his wounds. Thenceforth there was neither dance nor feast to which Brule was not invited; and when he wished to return to his countrymen, a party of Iroquois guided him four days on his way. He reached the friendly Hurons in safety, and joined them on their yearly descent to meet the French traders at Montreal.

Brule’s adventures find in some points their counterpart in those of his commander on the winter hunting-grounds of his Huron allies. As we turn the ancient, worm-eaten page which preserves the simple record of his fortunes, a wild and dreary scene rises before the mind, — a chill November air, a murky sky, a cold lake, bare and shivering forests, the earth strewn with crisp brown leaves, and, by the water-side, the bark sheds and smoking camp-fires of a band of Indian hunters. Champlain was of the party. There was ample occupation for his gun, for the morning was vocal with the clamor of wild-fowl, and his evening meal was enlivened by the rueful music of the wolves. It was a lake north or northwest of the site of Kingston. On the borders of a neighboring river, twenty-five of the Indians had been busied ten days in preparing for their annual deer-hunt. They planted posts interlaced with boughs in two straight converging lines, each extending mere than half a mile through forests and swamps. At the angle where they met was made a strong enclosure like a pound. At dawn of day the hunters spread themselves through the woods, and advanced with shouts, clattering of sticks, and howlings like those of wolves, driving the deer before them into the enclosure, where others lay in wait to dispatch them with arrows and spears.

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

Champlain was in the woods with the rest, when he saw a bird whose novel appearance excited his attention; and, gun in hand, he went in pursuit. The bird, flitting from tree to tree, lured him deeper and deeper into the forest; then took wing and vanished. The disappointed sportsman tried to retrace his steps. But the day was clouded, and he had left his pocket-compass at the camp. The forest closed around him, trees mingled with trees in endless confusion. Bewildered and lost, he wandered all day, and at night slept fasting at the foot of a tree. Awaking, he wandered on till afternoon, when he reached a pond slumbering in the shadow of the woods. There were water-fowl along its brink, some of which he shot, and for the first time found food to allay his hunger. He kindled a fire, cooked his game, and, exhausted, blanketless, drenched by a cold rain, made his prayer to Heaven, and again lay down to sleep. Another day of blind and weary wandering succeeded, and another night of exhaustion. He had found paths in the wilderness, but they were not made by human feet. Once more roused from his shivering repose, he journeyed on till he heard the tinkling of a little brook, and bethought him of following its guidance, in the hope that it might lead him to the river where the hunters were now encamped. With toilsome steps he followed the infant stream, now lost beneath the decaying masses of fallen trunks or the impervious intricacies of matted “windfalls,” now stealing through swampy thickets or gurgling in the shade of rocks, till it entered at length, not into the river, but into a small lake. Circling around the brink, he found the point where the brook ran out and resumed its course. Listening in the dead stillness of the woods, a dull, hoarse sound rose upon his ear. He went forward, listened again, and could plainly hear the plunge of waters. There was light in the forest before him, and, thrusting himself through the entanglement of bushes, he stood on the edge of a meadow. Wild animals were here of various kinds; some skulking in the bordering thickets, some browsing on the dry and matted grass. On his right rolled the river, wide and turbulent, and along its bank he saw the portage path by which the Indians passed the neighboring rapids. He gazed about him. The rocky hills seemed familiar to his eye. A clew was found at last; and, kindling his evening fire, with grateful heart he broke a long fast on the game he had killed. With the break of day he descended at his ease along the bank, and soon descried the smoke of the Indian fires curling in the heavy morning air against the gray borders of the forest. The joy was great on both sides. The Indians had searched for him without ceasing; and from that day forth his host, Durantal, would never let him go into the forest alone.

They were thirty-eight days encamped on this nameless river, and killed in that time a hundred and twenty deer. Hard frosts were needful to give them passage over the land of lakes and marshes that lay between them and the Huron towns. Therefore they lay waiting till the fourth of December; when the frost came, bridged the lakes and streams, and made the oozy marsh as firm as granite. Snow followed, powdering the broad wastes with dreary white. Then they broke up their camp, packed their game on sledges or on their shoulders, tied on their snowshoes, and began their march. Champlain could scarcely endure his load, though some of the Indians carried a weight fivefold greater. At night, they heard the cleaving ice uttering its strange groans of torment, and on the morrow there came a thaw. For four days they waded through slush and water up to their knees; then came the shivering northwest wind, and all was hard again. In nineteen days they reached the town of Cahiague, and, lounging around their smoky lodge-fires, the hunters forgot the hardships of the past.

– Pioneers of France in the New World Part II, Chapter 14 by Francis Parkman

This was about Explorers Indians, together.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Introduction.

If, at times, it may seem that range has been allowed to fancy, it is so in appearance only; since the minutest details of narrative or description rest on authentic documents or on personal observation.

Faithfulness to the truth of history involves far more than a research, however patient and scrupulous, into special facts. Such facts may be detailed with the most minute exactness, and yet the narrative, taken as a whole, may be unmeaning or untrue. The narrator must seek to imbue himself with the life and spirit of the time. He must study events in their bearings near and remote; in the character, habits, and manners of those who took part in them, he must himself be, as it were, a sharer or a spectator of the action he describes.

With respect to that special research which, if inadequate, is still in the most emphatic sense indispensable, it has been the writer’s aim to exhaust the existing material of every subject treated. While it would be folly to claim success in such an attempt, he has reason to hope that, so far at least as relates to the present volume, nothing of much importance has escaped him. With respect to the general preparation just alluded to, he has long been too fond of his theme to neglect any means within his reach of making his conception of it distinct and true.

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

Here is a Kindle version: Complete Works for just $2.

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Biography of Samuel de Champlain.

- Article on New France in North America.

- From the Canada History Project.

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.