“You are a liar.” “Which way did you go?” “By what rivers?” “By what lakes?” “Who went with you?” They pursued the truth: Was Champlain betrayed?

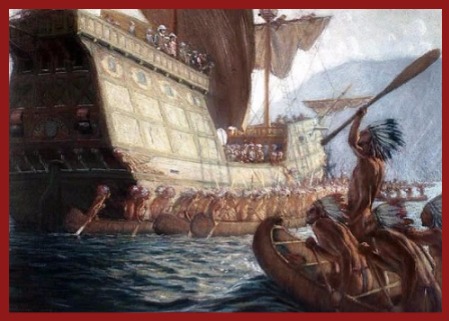

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously on Parkman

First, the pipes were passed to Champlain. Then, for full half an hour, the assembly smoked in silence. At length, when the fitting time was come, he addressed them in a speech in which he declared, that, moved by affection for them, he visited their country to see its richness and its beauty, and to aid them in their wars; and he now begged them to furnish him with four canoes and eight men, to convey him to the country of the Nipissings, a tribe dwelling northward on the lake which bears their name.

His audience looked grave, for they were but cold and jealous friends of the Nipissings. For a time they discoursed in murmuring tones among themselves, all smoking meanwhile with redoubled vigor. Then Tessouat, chief of these forest republicans, rose and spoke in behalf of all:

“We always knew you for our best friend among the Frenchmen. We love you like our own children. But why did you break your word with us last year when we all went down to meet you at Montreal, to give you presents and go with you to war? You were not there, but other Frenchmen were there who abused us. We will never go again. As for the four canoes, you shall have them if you insist upon it; but it grieves us to think of the hardships you must endure. The Nipissings have weak hearts. They are good for nothing in war, but they kill us with charms, and they poison us. Therefore we are on bad terms with them. They will kill you, too.”

Such was the pith of Tessouat’s discourse, and at each clause the conclave responded in unison with an approving grunt.

Champlain urged his petition; sought to relieve their tender scruples in his behalf; assured them that he was charm-proof, and that he feared no hardships. At length he gained his point. The canoes and the men were promised, and, seeing himself as he thought on the highway to his phantom Northern Sea, he left his entertainers to their pipes, and with a light heart issued from the close and smoky den to breathe the fresh air of the afternoon. He visited the Indian fields, with their young crops of pumpkins, beans, and French peas, — the last a novelty obtained from the traders. Here, Thomas, the interpreter, soon joined him with a countenance of ill news. In the absence of Champlain, the assembly had reconsidered their assent. The canoes were denied.

With a troubled mind he hastened again to the hall of council, and addressed the naked senate in terms better suited to his exigencies than to their dignity:

“I thought you were men; I thought you would hold fast to your word: but I find you children, without truth. You call yourselves my friends, yet you break faith with me. Still I would not incommode you; and if you cannot give me four canoes, two will Serve.”

The burden of the reply was, rapids, rocks, cataracts, and the wickedness of the Nipissings. “We will not give you the canoes, because we are afraid of losing you,” they said.

“This young man,” rejoined Champlain, pointing to Vignau, who sat by his side, “has been to their country, and did not find the road or the people so bad as you have said.”

“Nicolas,” demanded Tessouat, “did you say that you had been to the Nipissings?”

The impostor sat mute for a time, and then replied, “Yes, I have been there.”

Hereupon an outcry broke from the assembly, and they turned their eyes on him askance, “as if,” says Champlain, “they would have torn and eaten him.”

“You are a liar,” returned the unceremonious host; “you know very well that you slept here among my children every night, and got up again every morning; and if you ever went to the Nipissings, it must have been when you were asleep. How can you be so impudent as to lie to your chief, and so wicked as to risk his life among so many dangers? He ought to kill you with tortures worse than those with which we kill our enemies.”

Champlain urged him to reply, but he sat motionless and dumb. Then he led him from the cabin, and conjured him to declare if in truth he had seen this sea of the north. Vignan, with oaths, affirmed that all he had said was true. Returning to the council, Champlain repeated the impostor’s story — how he had seen the sea, the wreck of an English ship, the heads of eighty Englishmen, and an English boy, prisoner among the Indians.

At this, an outcry rose louder than before, and the Indians turned in ire upon Vignan.

“You are a liar.” “Which way did you go?” “By what rivers?” “By what lakes?” “Who went with you?”

Vignan had made a map of his travels, which Champlain now produced, desiring him to explain it to his questioners; but his assurance failed him, and he could not utter a word.

Champlain was greatly agitated. His heart was in the enterprise, his reputation was in a measure at stake; and now, when he thought his triumph so near, he shrank from believing himself the sport of an impudent impostor. The council broke up, — the Indians displeased and moody, and he, on his part, full of anxieties and doubts.

“I called Vignau to me in presence of his companions,” he says. “I told him that the time for deceiving me was ended; that he must tell me whether or not he had really seen the things he had told of; that I had forgotten the past, but that, if he continued to mislead me, I would have him hanged without mercy.”

Vignau pondered for a moment; then fell on his knees, owned his treachery, and begged forgiveness. Champlain broke into a rage, and, unable, as he says, to endure the sight of him, ordered him from his presence, and sent the interpreter after him to make further examination. Vanity, the love of notoriety, and the hope of reward, seem to have been his inducements; for he had in fact spent a quiet winter in Tessonat’s cabin, his nearest approach to the northern sea; and he had flattered himself that he might escape the necessity of guiding his commander to this pretended discovery. The Indians were somewhat exultant.

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

“Why did you not listen to chiefs and warriors, instead of believing the lies of this fellow?” And they counseled Champlain to have him killed at once, adding, “Give him to us, and we promise you that he shall never lie again.”

No motive remaining for farther advance, the party set out on their return, attended by a fleet of forty canoes bound to Montreal for trade. They passed the perilous rapids of the Calumet, and were one night encamped on an island, when an Indian, slumbering in an uneasy posture, was visited with a nightmare. He leaped up with a yell, screamed, that somebody was killing him, and ran for refuge into the river. Instantly all his companions sprang to their feet, and, hearing in fancy the Iroquois war-whoop, took to the water, splashing, diving, and wading up to their necks, in the blindness of their fright. Champlain and his Frenchmen, roused at the noise, snatched their weapons and looked in vain for an enemy. The panic-stricken warriors, reassured at length, waded crestfallen ashore, and the whole ended in a laugh.

At the Chaudiere, a contribution of tobacco was collected on a wooden platter, and, after a solemn harangue, was thrown to the guardian Manitou. On the seventeenth of June they approached Montreal, where the assembled traders greeted them with discharges of small arms and cannon. Here, among the rest, was Champlain’s lieutenant, Du Parc, with his men, who had amused their leisure with hunting, and were reveling in a sylvan abundance, while their baffled chief, with worry of mind, fatigue of body, and a Lenten diet of half-cooked fish, was grievously fallen away in flesh and strength. He kept his word with DeVignau, left the scoundrel unpunished, bade farewell to the Indians, and, promising to rejoin then the next year, embarked in one of the trading-ships for France.

1615. DISCOVERY OF LAKE HURON

In New France, spiritual and temporal interests were inseparably blended, and, as will hereafter appear, the conversion of the Indians was used as a means of commercial and political growth. But, with the single-hearted founder of the colony, considerations of material advantage, though clearly recognized, were no less clearly subordinate. He would fain rescue from perdition a people living, as he says, “like brute beasts, without faith, without law, without religion, without God.” While the want of funds and the indifference of his merchant associates, who as yet did not fully see that their trade would find in the missions its surest ally, were threatening to wreck his benevolent schemes, he found a kindred spirit in his friend Houd, secretary to the King, and comptroller-general of the salt-works of Bronage. Near this town was a convent of Recollet friars, some of whom were well known to Houel. To them he addressed himself; and several of the brotherhood, “inflamed,” we are told, “with charity,” were eager to undertake the mission. But the Recollets, mendicants by profession, were as weak in resources as Champlain himself. He repaired to Paris, then filled with bishops, cardinals, and nobles, assembled for the States-General. Responding to his appeal, they subscribed fifteen hundred livres for the purchase of vestments, candles, and ornaments for altars. The King gave letters patent in favor of the mission, and the Pope gave it his formal authorization. By this instrument the papacy in the person of Paul the Fifth virtually repudiated the action of the papacy in the person of Alexander the Sixth, who had proclaimed all America the exclusive property of Spain.

The Recollets form a branch of the great Franciscan Order, founded early in the thirteenth century by Saint Francis of Assisi. Saint, hero, or madman, according to the point of view from which he is regarded, he belonged to an era of the Church when the tumult of invading heresies awakened in her defense a band of impassioned champions, widely different from the placid saints of an earlier age. He was very young when dreams and voices began to reveal to him his vocation, and kindle his high-wrought nature to sevenfold heat. Self-respect, natural affection, decency, became in his eyes but stumbling-blocks and snares. He robbed his father to build a church; and, like so many of the Roman Catholic saints, confounded filth with humility, exchanged clothes with beggars, and walked the streets of Assisi in rags amid the hootings of his townsmen. He vowed perpetual poverty and perpetual beggary, and, in token of his renunciation of the world, stripped himself naked before the Bishop of Assisi, and then begged of him in charity a peasant’s mantle. Crowds gathered to his fervid and dramatic eloquence. His handful of disciples multiplied, till Europe became thickly dotted with their convents. At the end of the eighteenth century, the three Orders of Saint Francis numbered a hundred and fifteen thousand friars and twenty-eight thousand nuns. Four popes, forty-five cardinals, and forty-six canonized martyrs were enrolled on their record, besides about two thousand more who had shed their blood for the faith. Their missions embraced nearly all the known world; and, in 1621, there were in Spanish America alone five hundred Franciscan convents.

In process of time the Franciscans had relaxed their ancient rigor; but much of their pristine spirit still subsisted in the Recollets, a reformed branch of the Order, sometimes known as Franciscans of the Strict Observance.

Four of their number were named for the mission of New France, — Denis Jamay, Jean Dolbean, Joseph le Caron, and the lay brother Pacifique du Plessis. “They packed their church ornaments,” says Champlain, “and we, our luggage.” All alike confessed their sins, and, embarking at Honfleur, reached Quebec at the end of May, 1615.

– Pioneers of France in the New World Part II, Chapter 13 by Francis Parkman

Champlain betrayed began this passage; then the story moved on.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Introduction.

If, at times, it may seem that range has been allowed to fancy, it is so in appearance only; since the minutest details of narrative or description rest on authentic documents or on personal observation.

Faithfulness to the truth of history involves far more than a research, however patient and scrupulous, into special facts. Such facts may be detailed with the most minute exactness, and yet the narrative, taken as a whole, may be unmeaning or untrue. The narrator must seek to imbue himself with the life and spirit of the time. He must study events in their bearings near and remote; in the character, habits, and manners of those who took part in them, he must himself be, as it were, a sharer or a spectator of the action he describes.

With respect to that special research which, if inadequate, is still in the most emphatic sense indispensable, it has been the writer’s aim to exhaust the existing material of every subject treated. While it would be folly to claim success in such an attempt, he has reason to hope that, so far at least as relates to the present volume, nothing of much importance has escaped him. With respect to the general preparation just alluded to, he has long been too fond of his theme to neglect any means within his reach of making his conception of it distinct and true.

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

Here is a Kindle version: Complete Works for just $2.

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Biography of Samuel de Champlain.

- Article on New France in North America.

- From the Canada History Project.

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.