A sin, a vice, a crime, are the objects of theology, ethics, and jurisprudence. Whenever their judgments agree, they corroborate each other; but as often as they differ . . . .

Justinian Code Published, featuring a series of excerpts selected from The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by Edward Gibbon published in 1788.

Previously in Justinian Code Published. Now we continue.

Time: 534

Place: Constantinople

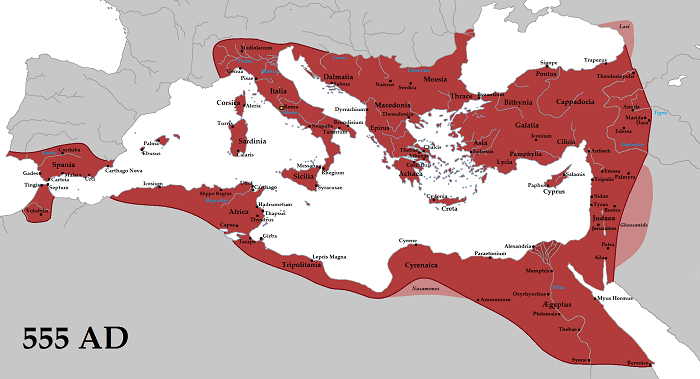

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

The Cornelian and afterward the Pompeian and Julian laws introduced a new system of criminal jurisprudence; and the emperors, from Augustus to Justinian, disguised their increasing rigor under the names of the original authors.

But the invention and frequent use of extraordinary pains proceeded from the desire to extend and conceal the progress of despotism. In the condemnation of illustrious Romans the senate was always prepared to confound, at the will of their masters, the judicial and legislative powers. It was the duty of the governors to maintain the peace of their province by the arbitrary and rigid administration of justice; the freedom of the city evaporated in the extent of empire, and the Spanish malefactor, who claimed the privilege of a Roman, was elevated by the command of Galba on a fairer and more lofty cross. Occasional rescripts issued from the throne to decide the questions which, by their novelty or importance, appeared to surpass the authority and discernment of a proconsul. Transportation and beheading were reserved for honorable persons; meaner criminals were either hanged, or burned, or buried in the mines, or exposed to the wild beasts of the amphitheatre. Armed robbers were pursued and extirpated as the enemies of society; the driving away of horses or cattle was made a capital offence, but simple theft was uniformly considered as a mere civil and private injury. The degrees of guilt and the modes of punishment were too often determined by the discretion of the rulers, and the subject was left in ignorance of the legal danger which he might incur by every action of his life.

A sin, a vice, a crime, are the objects of theology, ethics, and jurisprudence. Whenever their judgments agree, they corroborate each other; but as often as they differ a prudent legislator appreciates the guilt and punishment according to the measure of social injury. On this principle the most daring attack on the life and property of a private citizen is judged less atrocious than the crime of treason or rebellion, which invades the majesty of the republic; the obsequious civilians unanimously pronounced that the republic is contained in the person of its chief; and the edge of the Julian law was sharpened by the incessant diligence of the emperors. The licentious commerce of the sexes may be tolerated as an impulse of nature, or forbidden as a source of disorder and corruption; but the fame, the fortunes, the family of the husband, are seriously injured by the adultery of the wife. The wisdom of Augustus, after curbing the freedom of revenge, applied to this domestic offence the animadversion of the laws; and the guilty parties, after the payment of heavy forfeitures and fines, were condemned to long or perpetual exile in two separate islands.

Religion pronounces an equal censure against the infidelity of the husband; but, as it is not accompanied by the same civil effects, the wife was never permitted to vindicate her wrong; and the distinction of simple or double adultery, so familiar and so important in the canon law, is unknown to the jurisprudence of the Code and the Pandects. I touch with reluctance and despatch with impatience a more odious vice, of which modesty rejects the name, and nature abominates the idea. The primitive Romans were infected by the example of the Etruscans and Greeks; in the mad abuse of prosperity and power, every pleasure that is innocent was deemed insipid; and the Scatinian law, which had been extorted by an act of violence, was insensibly abolished by the lapse of time and the multitude of criminals.

By this law the rape, perhaps the seduction, of an ingenuous youth was compensated as a personal injury by the poor damages of ten thousand sesterces, or fourscore pounds; the ravisher might be slain by the resistance or revenge of chastity; and I wish to believe that at Rome, as in Athens, the voluntary and effeminate deserter of his sex was degraded from the honors and the rights of a citizen. But the practice of vice was not discouraged by the severity of opinion; the indelible stain of manhood was confounded with the more venial transgressions of fornication and adultery, nor was the licentious lover exposed to the same dishonor which he impressed on the male or female partner of his guilt. From Catullus to Juvenal the poets accuse and celebrate the degeneracy of the times; and the reformation of manners was feebly attempted by the reason and authority of the civilians till the most virtuous of the Caesars proscribed the sin against nature as a crime against society.

A new spirit of legislation, respectable even in its error, arose in the empire with the religion of Constantine. The laws of Moses were received as the divine original of justice, and the Christian princes adapted their penal statutes to the degrees of moral and religious turpitude. Adultery was first declared to be a capital offence: the frailty of the sexes was assimilated to poison or assassination, to sorcery or parricide; the same penalties were inflicted on the passive and active guilt of pederasty, and all criminals of free or servile condition were either drowned or beheaded, or cast alive into the avenging flames. The adulterers were spared by the common sympathy of mankind; but the lovers of their own sex were pursued by general and pious indignation: the impure manners of Greece still prevailed in the cities of Asia, and every vice was fomented by the celibacy of the monks and clergy.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.