The execution of the Alban dictator, who was dismembered by eight horses, is represented by Livy as the first and the last instance of Roman cruelty in the punishment of the most atrocious crimes.

Justinian Code Published, featuring a series of excerpts selected from The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by Edward Gibbon published in 1788.

Previously in Justinian Code Published. Now we continue.

Time: 534

Place: Constantinople

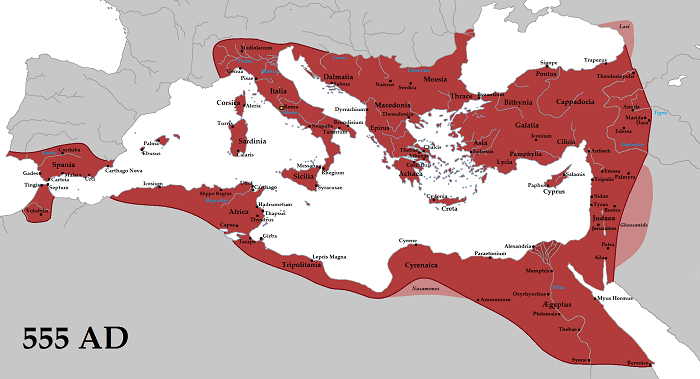

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

3. Nature and society impose the strict obligation of repairing an injury; and the sufferer by private injustice acquires a personal right and a legitimate action. If the property of another be entrusted to our care, the requisite degree of care may rise and fall according to the benefit which we derive from such temporary possession; we are seldom made responsible for inevitable accident, but the consequences of a voluntary fault must always be imputed to the author. A Roman pursued and recovered his stolen goods by a civil action of theft; they might pass through a succession of pure and innocent hands, but nothing less than a prescription of thirty years could extinguish his original claim. They were restored by the sentence of the praetor, and the injury was compensated by double, or threefold, or even quadruple damages, as the deed had been perpetrated by secret fraud or open rapine, as the robber had been surprised in the fact or detected by a subsequent research. The Aquilian law defended the living property of a citizen, his slaves and cattle, from the stroke of malice or negligence: the highest price was allowed that could be ascribed to the domestic animal at any moment of the year preceding his death; a similar latitude of thirty days was granted on the destruction of any other valuable effects. A personal injury is blunted or sharpened by the manners of the times and the sensibility of the individual: the pain or the disgrace of a word or blow cannot easily be appreciated by a pecuniary equivalent.

The rude jurisprudence of the decemvirs had confounded all hasty insults, which did not amount to the fracture of a limb by condemning the aggressor to the common penalty of twenty-five asses. But the same denomination of money was reduced in three centuries from a pound to the weight of half an ounce: and the insolence of a wealthy Roman indulged himself in the cheap amusement of breaking and satisfying the law of the Twelve Tables. Veratius ran through the streets striking on the face the inoffensive passengers, and his attendant purse-bearer immediately silenced their clamors by the legal tender of twenty-five pieces of copper, about the value of one shilling. The equity of the prætors examined and estimated the distinct merits of each particular complaint. In the adjudication of civil damages the magistrate assumed the right to consider the various circumstances of time and place, of age and dignity, which may aggravate the shame and sufferings of the injured person: but if he admitted the idea of a fine, a punishment, an example, he invaded the province, though, perhaps, he supplied the defects of the criminal law.

IV. The execution of the Alban dictator, who was dismembered by eight horses, is represented by Livy as the first and the last instance of Roman cruelty in the punishment of the most atrocious crimes. But this act of justice, or revenge, was inflicted on a foreign enemy in the heat of victory and at the command of a single man. The Twelve Tables afford a more decisive proof of the national spirit, since they were framed by the wisest of the senate, and accepted by the free voices of the people; yet these laws, like the statutes of Draco, are written in characters of blood. They approve the inhuman and unequal principle of retaliation; and the forfeit of an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, a limb for a limb, is rigorously exacted, unless the offender can redeem his pardon by a fine of three hundred pounds of copper. The decemvirs distributed with much liberality the slighter chastisements of flagellation and servitude; and nine crimes of a very different complexion are adjudged worthy of death.

1. Any act of treason against the state, or of correspondence with the public enemy. The mode of execution was painful and ignominious: the head of the degenerate Roman was shrouded in a veil, his hands were tied behind his back, and after he had been scourged by the lictor, he was suspended in the midst of the Forum on a cross or inauspicious tree.

2. Nocturnal meetings in the city; whatever might be the pretence, of pleasure, or religion, or the public good.

3. The murder of a citizen; for which the common feelings of mankind demand the blood of the murderer. Poison is still more odious than the sword or dagger; and we are surprised to discover in two flagitious events how early such subtle wickedness has infected the simplicity of the republic, and the chaste virtues of the Roman matrons. The parricide, who violated the duties of nature and gratitude, was cast into the river or the sea, enclosed in a sack; and a cock, a viper, a dog, and a monkey were successively added as the most suitable companions. Italy produces no monkeys; but the want could never be felt till the middle of the sixth century first revealed the guilt of a parricide.

4. The malice of an incendiary. After the previous ceremony of whipping, he himself was delivered to the flames; and in this example alone our reason is tempted to applaud the justice of retaliation.

5. Judicial perjury. The corrupt or malicious witness was thrown headlong from the Tarpeian Rock to expiate his falsehood, which was rendered still more fatal by the severity of the penal laws and the deficiency of written evidence.

6. The corruption of a judge who accepted bribes to pronounce an iniquitous sentence.

7. Libels and satires, whose rude strains sometimes disturbed the peace of an illiterate city. The author was beaten with clubs, a worthy chastisement, but it is not certain that he was left to expire under the blows of the executioner.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.