On Sunday, in his imperial robes and attended by a magnificent retinue, Frederick went to his coronation, as king of Jerusalem, in the Church of the Sepulcher.

Saracens’ Treaty with Frederick II Ends the 6th. Crusade

Introduction an excerpt selected from The Crusades by Sir George W. Cox published in 1890:

After the 5th. Crusade the Christians had a truce with Saphadin, who had succeeded his brother, Saladin. The Pope was dissatisfied with this and preached another Crusade. Three expeditions sailed, only one counted for much, the one lead by Frederick II. Furious at Frederick’s delays, the Pope, disregarding excuses of illness, excommunicated him.

And now, Sir George W. Cox.

Time: 1228

Place: Palestine

Public domain from Wikipedia.

After his excommunication, Frederick appealed not to the Pope, but to the sovereigns of Christendom. His illness, he said, had been real, the accusations of the Pope wanton and cruel.

“The Christian charity which should hold all things together is dried up at its source, in its stem, not in its branches. What had the Pope done in England but stir up the barons against John, and then abandon them to death or ruin? The whole world paid tribute to his avarice. His legates were everywhere, gathering where they had not sown, and reaping where they had not strawed.”

But although he thus dealt in language as furious as that of the Pope, the thought of breaking definitely with him and of casting aside his crusading vow as worthless mockery never seems to have entered his mind. He undertook to bring his armies together again with all speed, and to set off on his expedition. His promise only brought him into fresh trouble with the Pope, who in the Holy Week next following laid under interdict every place in which Frederick might happen to be. If this censure should be treated with contempt, his subjects were at once absolved from their allegiance.

The Emperor went on steadily with his preparations, and then went to Brundisium. He was met by papal messengers who strictly forbade him to leave Italy until he had offered satisfaction for his offences against the Church. In his turn Frederick, having sailed to Otranto, sent his own envoys to the Pope to demand the removal of the interdict; and these, of course, were dismissed with contempt.

In September the Emperor landed at Ptolemais; but the emissaries of the Pope had preceded him, and he found himself under the ban of the clergy and shunned by their partisans. The patriarch and the masters of the military orders were to see that none served under his polluted banners. The charge was given to willing servants: but Frederick found friends in the Teutonic Knights under their grand master Herman de Salza, as well as with the body of pilgrims generally. He determined to possess himself of Joppa, and summoned all the crusaders to his aid.

The Templars refused to stir, if any orders were to be issued in his name; and Frederick agreed that they should run in the name of God and Christendom. But while the enemy was aided greatly by the divisions among the Christians, the death of the Damascene sultan Moadhin was of little use to Frederick. The Egyptian sultan, Kameel, was now in a position of greater independence, and his eagerness for an alliance with the Emperor had rapidly cooled down.

Frederick, on his side, still resolved to try the effect of negotiation. His demands extended at first, it is said, to the complete restoration of the Latin kingdom, and ended, if we are to believe Arabian chroniclers, in almost abject supplications. At length a treaty was signed. It surrendered to the Emperor the whole of Jerusalem except the Temple or mosque of Omar, the keys of which were to be retained by the Saracens; but Christians, under certain conditions, might be allowed to enter it for the purpose of prayer. It further restored to the Christians the towns of Jaffa, Bethlehem, and Nazareth.

To Frederick the conclusion of this treaty was a reason for legitimate satisfaction. It enabled him to hasten back to his own dominions, where a papal army was ravaging Apulia and threatening Sicily. One task only remained for him in the East. He must pay his vows at the Holy Sepulcher. But here also the hand of the Pope lay heavy upon him. Not merely Jerusalem, but the Sepulcher itself, passed under the interdict as he entered the gates of the city, and the infidel Moslem saw the churches closed and all worship suspended at the approach of the Christian Emperor.

On Sunday, in his imperial robes and attended by a magnificent retinue, Frederick went to his coronation, as king of Jerusalem, in the Church of the Sepulcher. Not a single ecclesiastic was there to take part in the ceremony. The archbishops of Capua and Palermo stood aloof, while Frederick, taking the crown from the high altar, placed it on his own head. By his orders his friend Herman de Salza read an address, in which the Emperor acquitted the Pope for his hard judgment of him and for his excommunication, and added that a real knowledge of the facts would have led him to speak not against him, but in his favor. He confessed his desire to put to shame the false friends of Christ, his accusers and slanderers, by the restoration of peace and unity, and to humble himself before God and before his vicar upon earth.

From the Saracens he won golden opinions. The cadi silenced a muezzin who had to proclaim the hour of prayer from a minaret near the house in which the Emperor lodged, because he added to his call the question, “How is it possible that God had for his son Jesus the son of Mary?” Frederick marked the silence of the crier when the hour of prayer came round. On learning the cause he rebuked the cadi for neglecting, on his account, his duty and his religion, and warned him that if he should visit him in his kingdom he would find no such ill-judged deference. He showed no dissatisfaction, it is said, with the inscription which declared that Saladin had purified the city from those who worshipped many gods, or any displeasure when the Mahometans in his train fell on their knees at the times for prayer. His thoughts about the Christians were shown, it was supposed, when, seeing the windows of the Holy Chapel barred to keep out the birds which might defile it, he asked: “You may keep out the birds; but how will you keep out the swine?”

In glowing terms Frederick wrote to the sovereigns of Europe, announcing the splendid success which he had achieved rather by the pen than by the sword. He scarcely knew what a rock of offence he had raised up among Christians and Moslems alike. By a few words on a sheet of parchment the Christian Emperor had deprived his people of the hope of getting their sins forgiven by murdering unbelievers; by the same words the Moslem Sultan had prevented his subjects from insuring an entrance to the delights of paradise by the slaughter of the Nazarenes.

From Gerold, Patriarch of Jerusalem, a letter went to the Pope, full of virulent abuse of the Emperor as a traitor, an apostate, and a robber; but even before he received this letter Gregory had condemned what he chose to consider as a monstrous attempt to reconcile Christ and Belial, and to set up Mahomet as an object of worship in the temple of God. “The antagonist of the Cross,” he wrote, “the enemy of the faith and of all chastity, the wretch doomed to hell, is lifted up for adoration, by a perverse judgment, and by an intolerable insult to the Saviour, to the lasting disgrace of the Christian name and the contempt of all the martyrs who have laid down their lives to purify the Holy Land from the defilements of the Saracens.”

But Frederick, in his turn, could be firm and unyielding. He returned from Jerusalem to Joppa, from Joppa to Ptolemais; and there learning that a proposal had been made to establish a new order of knights, he declared that no one should, without his consent, levy soldiers within his dominion. Summoning all the Christians within the city to the broad plain without the gates, he spoke his mind freely about the conduct of the Patriarch and the Templars, with all who aided and abetted them, and insisted that all the pilgrims, having now paid their vows, should return at once to Europe. On this point he was inexorable. His archers took possession of the churches; two friars who denounced him from the pulpit were scourged through the streets; the Patriarch was shut up in his palace; and the commands of the Emperor were carried out.

Frederick returned to Europe, to find that the Pope had been stirring up Albert of Austria to rebel against him, and that the papal forces were in command of John of Brienne, who may have been the author of the false news of Frederick’s death, and who certainly proclaimed himself as the only emperor. To the Pope, Frederick sent his envoys, Herman de Salza at their head. They were dismissed with contempt; and their master was again placed under the greater excommunication with the Albigensians, the Poor Men of Lyons, the Arnoldists, and other heretics who, in the eyes of the faithful, were the worst enemies of the Christian church. Such was the reward of the man who had done more toward the reestablishment of the Latin kingdom in Palestine than had been done by the lion-hearted Richard, and who, it may fairly be said, had done it without shedding a drop of blood.

This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information here and here.

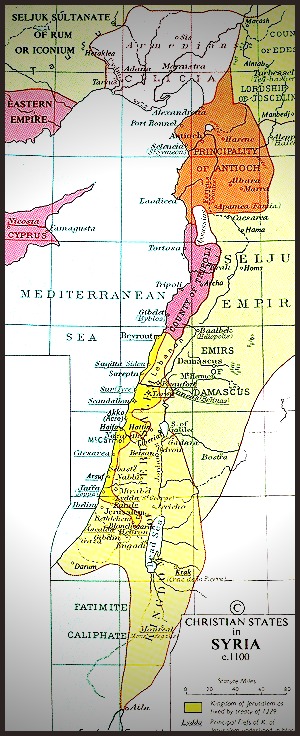

Original link for map: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sixth_Crusade#/media/File:Map_Crusader_states_ca._1100.jpg

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.