. . . if Europe had any moral conscience left, it would have been shocked as it was never shocked before.

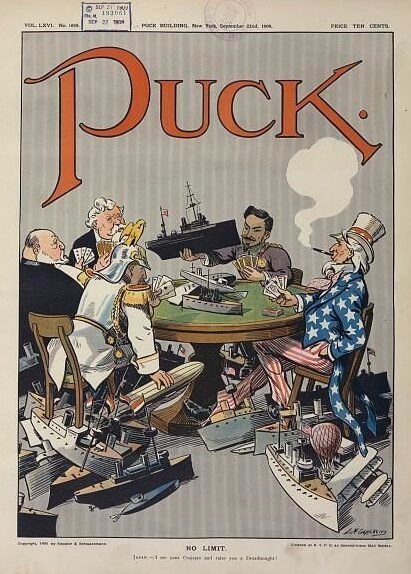

Militarism Before World War I, featuring a series of essays published before the war. This concludes our essay by Norman Angell.

Previously in Militarism Before World War I. Now we continue.

Time: Early 20th. century

Public domain image from Wikipedia .

Italy struck at Turkey for “honor,” for prestige — for the purpose of impressing Europe. And one may hope that Europe (after reading the reports of Reuter, The Times, the Daily Mirror, and the New York World as to the methods which Italy is using in vindicating her “honor”) is duly impressed, and that Italian patriots are satisfied with these new glories added to Italian history. It is all they will get.

Or rather, will they get much more: for Italy, as unhappily for the balance of Europe, the substance will be represented by the increase of very definite every-day difficulties — the high cost of living, the uncertainty of employment, the very deep problems of poverty, education, government, well-being. These remain — worsened. And this — not the spectacular clash of arms, or even the less spectacular killing of unarmed Arab men, women, and children — constitute the real “struggle for life among men.” But the dilettanti of “high politics” are not interested. For those who still take their language and habits of thought from the days of the sailing-ship, still talk of “possessing” territory, still assume that tribute in some form is possible, still imply that the limits of commercial and industrial activity are dependent upon the limits of political dominion, the struggle is represented by this futile physical collision of groups, which, however victory may go, leaves the real solution further off than ever.

We know what preceded this war: if Europe had any moral conscience left, it would have been shocked as it was never shocked before. Turkey said: “We will submit Italy’s grievance to any tribunal that Europe cares to name, and abide by the result.” Italy said: “We don’t intend to have the case judged, but to take Tripoli. Hand it over — in twenty-four hours.” The Turkish Government said: “At least make it possible for us to face our own people. Call it a Protectorate; give us the shadow of sovereignty. Otherwise it is not robbery — to which we should submit — but gratuitous degradation; we should abdicate before the eyes of our own people. We will do anything you like.” “In that case,” said Italy, “we will rob; and we will go to war.”

It was not merely robbery that the Italian Government intended, but they meant from the first that it should be war — to “dish the Socialists,” to play some sordid intrigue of internal politics.

The ultimatum was launched from the center of Christendom — the city which lodges the titular head of the Universal Church — to teach to the Mohammedan world what may be expected from a modern Christian Government with its back to eighteen centuries of Christian teaching.

We, Christendom, spend scores of millions — hundreds of millions, it may be — in the propagation of the Christian faith: numberless men and women gave their lives for it, our fathers spent two centuries in unavailing warfare for the capture of some of its symbols. Presumably, therefore, we attach some value to its principles, deeming them of some worth in the defense of human society.

Or do we believe nothing of the sort? Is our real opinion that these things at bottom don’t matter — or matter so little that for the sake of robbing the squalid belongings of a few Arab tribes, or playing some mean game of party politics, they can be set aside in a whoop of “patriotism”?

Our press waxes indignant in this particular case, and that is the end of it. But we do not see that we are to blame, that it is all the outcome of a conception of politics which we are forever ready to do our part to defend, to do daily our part to uphold.

And those of us who try in our feeble way to protest against this conception of politics and patriotism, where everything stands on its head; where the large is made to appear the great, and the great is made to appear the small, are derided as sentimentalists, Utopians. As though anything could be more sentimental, more divorced from the sense of reality, than the principles which lead us to a condition of things like these; as though anything could be more wildly, burlesquely Utopian than the idea that efforts of the kind that the Italian people are now making, the energy they are now spending, could ever achieve anything of worth.

Is it not time that the man in the street, verily, I believe, less deluded by diplomatic jargon than his betters, less the slave of an obsolete phraseology, insisted that the experts in the high places acquired some sense of the reality of things, of proportion, some sense of figures, a little knowledge of industrial history, of the real processes of human cooperation?

At present Europe is quite indifferent to Italy’s behavior. The Chancelleries, which will go to enormous trouble and take enormous risks and concoct alliances and counter-alliances when there is territory to be seized, remain cold when crimes of this sort are committed. And they remain cold because they believe that Turkey alone is concerned. They do not see that Italy has attacked not Turkey, but Europe; that we, more than Turkey, will pay the broken pots.

And there is a further reason: We still believe in these piracies; we believe they pay and that we may get our turn at some “swag” to-morrow. France is envied for her possession of Morocco; Germany for her increased authority over some pestilential African swamps. But when we realize that in these international burglaries there is no “swag,” that the whole thing is an illusion, that there are huge costs but no reward, we shall be on the road to a better tradition, which, while it may not give us international policing, may do better still — render the policing unnecessary. For when we have realized that the game is not worth the candle, when no one desires to commit aggression, the competition in armaments will have become a bad nightmare of the past.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.