In the modern world political dominion is playing a more and more effaced role as a factor in commerce . . . .

Militarism Before World War I, featuring a series of essays published before the war. This continues the one by Norman Angell.

Previously in Militarism Before World War I. Now we continue.

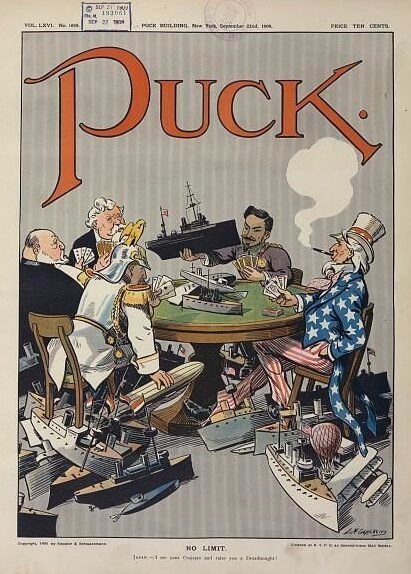

Time: Early 20th. century

Public domain image from Wikipedia .

The French, like their neighbors, are not interested in the Germans of the Champs-Elysees, but only in the Germans at Agadir: and it is for these latter that the diplomats fight, and the war budgets swell.

And from that silent and pacific expansion, which means so much both negatively and positively, attention is diverted to the banging of the war drum, and the dancing of the patriotic dervishes.

And on the other side we are to assume that Germany has during the period of France’s expansion — since the war — not expanded at all. That she has been throttled and cramped — that she has not had her place in the sun: and that is why she must fight for it and endanger the security of her neighbors.

Well, I put it to you again that all this in reality is false: that Germany has not been cramped or throttled; that, on the contrary, as we recognize when we get away from the mirage of the map, her expansion has been the wonder of the world. She has added 20,000,000 to her population — one-half the present population of France — during a period in which the French population has actually diminished. Of all the nations in Europe, she has cut the biggest swath in the development of world trade, industry, and influence. Despite the fact that she has not “expanded” in the sense of mere political dominion, a proportion of her population, equivalent to the white population of the whole colonial British Empire, make their living, or the best part of it, from the development and exploitation of territory outside her borders. These facts are not new, they have been made the text of thousands of political sermons preached in England itself during the last few years; but one side of their significance seems to have been missed.

We get, then, this: On the one side a nation extending enormously its political dominion and yet diminishing in national force, if by national force we mean the growth of a sturdy, enterprising, vigorous people. (I am not denying that France is both wealthy and comfortable, to a greater degree it may be than her rival; but she has not her colonies to thank for it — quite the contrary.) On the other side, we get immense expansion expressed in terms of those things — a growing and vigorous population and the possibility of feeding them — and yet the political dominion, speaking practically, has hardly been extended at all.

Such a condition of things, if the common jargon of high politics means anything, is preposterous. It takes nearly all meaning out of most that we hear about “primordial needs,” and the rest of it.

As a matter of fact, we touch here one of the vital confusions, which is at the bottom of most of the present political trouble between nations, and shows the power of the old ideas, and the old phraseology.

In the days of the sailing ship and the lumbering wagon dragging slowly over all but impassable roads, for one country to derive any considerable profit from another, it had, practically, to administer it politically. But the compound steam engine, the railway, the telegraph, have profoundly modified the elements of the whole problem. In the modern world political dominion is playing a more and more effaced role as a factor in commerce; the non-political factors have in practice made it all but inoperative. It is the case with every modern nation actually that the outside territories which it exploits most successfully are precisely those of which it does not “own” a foot. Even with the most characteristically colonial of all — Great Britain — the greater part of her overseas trade is done with countries which she makes no attempt to “own,” control, coerce, or dominate — and incidentally she has ceased to do any of these things with her colonies.

Millions of Germans in Prussia and Westphalia derive profit or make their living out of countries to which their political dominion in no way extends. The modern German exploits South America by remaining at home. Where, forsaking this principle, he attempts to work through political power, he approaches futility. German colonies are colonies “pour rire.” The Government has to bribe Germans to go to them; her trade with them is microscopic; and if the twenty millions who have been added to Germany’s population since the war had had to depend on their country’s political conquest they would have had to starve. What feeds them are countries which Germany has never “owned” and never hopes to “own”; Brazil, Argentina, the United States, India, Australia, Canada, Russia, France, and England. (Germany, which never spent a mark on its political conquest, to-day draws more tribute from South America than does Spain, which has poured out mountains of treasure and oceans of blood in its conquest.) These are Germany’s real colonies. Yet the immense interests which they represent, of really primordial concern to Germany, without which so many of her people would be actually without food, are for the diplomats and the soldiers quite secondary ones; the immense trade which they represent owes nothing to the diplomat, to Agadir incidents, to Dreadnoughts; it is the unaided work of the merchant and the manufacturer. All this diplomatic and military conflict and rivalry, this waste of wealth, the unspeakable foulness which Tripoli is revealing, are reserved for things which both sides to the quarrel could sacrifice, not merely without loss, but with profit. And Italy, whose statesmen have been faithful to all the old “axioms” (Heaven save the mark!) will discover it rapidly enough. Even her defenders are ceasing now to urge that she can possibly derive any real benefit from this colossal ineptitude.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Like!! Thank you for publishing this awesome article.