This series has four easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Agadir Crisis Backgrounder.

Introduction

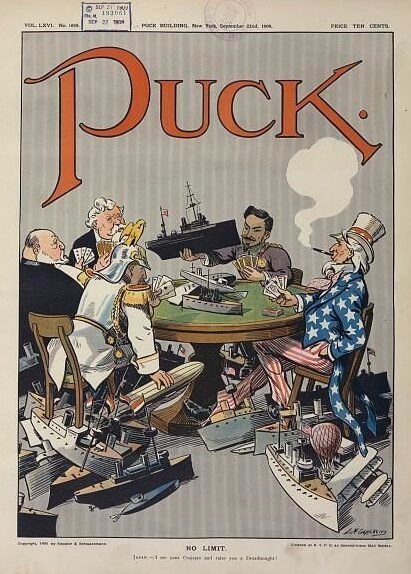

The Agadir Crisis was the milestone on the way to World War I. These are a couple of essays that were written before the war began.

Norman Angell was to win the Nobel Peace Prize in 1933 wrote this essay before the WWI began.

Time: Early 20th. century

Public domain image from Wikipedia .

The Press of Europe and America is very busy discussing the lessons of the diplomatic conflict which has just ended. And the outstanding impression which one gets from most of these essays in high politics — whether French, Italian, or British — is that we have been and are witnessing part of a great world movement, the setting in motion of Titanic forces “deep-set in primordial needs and impulses.”

For months those in the secrets of the Chancelleries have spoken with bated breath — as though in the presence of some vision of Armageddon. On the strength of this mere talk of war by the three nations, vast commercial interests have been embarrassed, fortunes have been lost and won on the Bourses, banks have suspended payment, some thousands have been ruined; while the fact that the fourth and fifth nations have actually gone to war has raised all sorts of further possibilities of conflict, not alone in Europe, but in Asia, with remoter danger of religious fanaticism and all its sequelae. International bitterness and suspicion in general have been intensified, and the one certain result of the whole thing is that immense burdens will be added in the shape of further taxation for armaments to the already heavy ones carried by the five or six nations concerned. For two or three hundred millions of people in Europe life, which with all the problems of high prices, labor wars, unsolved social difficulties, is none too easy as it is, will be made harder still.

The needs, therefore, that can have provoked a conflict of these dimensions must be “primordial” indeed. In fact, one authority assures us that what we have seen going on is “the struggle for life among men” — that struggle which has its parallel in the whole of sentient existence.

Well, I put it to you, as a matter worth just a moment or two of consideration, that this conflict is about nothing of the sort; that it is about a perfectly futile matter, one which the immense majority of the German, English, French, Italian, and Turkish people could afford to treat with the completest indifference. For, to the vast majority of these 250,000,000 people, more or less, it does not matter two straws whether Morocco or some vague, African swamp near the Equator is administered by German, French, Italian, or Turkish officials, so long as it is well administered. Or rather one should go further: if French, German, or Italian colonization of the past is any guide, the nation which wins in the conquest for territory of this sort has added a wealth-draining incubus.

This, of course, is preposterous; I am losing sight of the need for making provision for the future expansion of the race, of each party desiring to “find its place in the sun”; and heaven knows what.

Well, let us for a moment get away from phrases and examine a few facts usually ignored because they happen to be beneath our nose.

France has got a new empire, we are told; she has won a great victory; she is growing and expanding and is richer by something which her rivals are the poorer for not having.

Let us assume that she makes the same success of Morocco that she has made of her other possessions, of, say, Tunis, which represents one of the most successful of those operations of colonial expansion which have marked her history during the last forty years. What has been the precise effect on French prosperity?

In thirty years, at a cost of many million sterling (it is part of successful colonial administration in France never to let it be known what the colonies really cost) France has founded in Tunis a colony, in which to-day there are, excluding soldiers and officials, about 25,000 genuine French colonists: just the number by which the French population in France — the real France — is diminishing every six months! And the value of Tunis as a market does not even amount to the sum which France spends directly on its occupation and administration, to say nothing of the indirect extension of military burden which its conquest involves; and, of course, the market which it represents would still exist in some form, though England — or even Germany — administered the country.

In other words, France loses twice every year in her home population two colonies equivalent to Tunis — if we measure colonies in terms of communities made up of the race which has sprung from the mother country. And yet, if once in a generation her rulers and diplomats can point to 25,000 Frenchmen living artificially and exotically under conditions which must in the long run be inimical to their race, it is pointed to as “expansion” and as evidence that France is maintaining her position as a Great Power. A few years, as history goes, unless there is some complete change of tendencies which at present seem as strong as ever, the French race as we now know it will have ceased to exist, swamped without the firing, may be, of a single shot, by the Germans, Belgians, English, Italians, and Jews. There are to-day in France more Germans than there are Frenchmen in all the colonies that France has acquired in the last half-century, and German trade with France outweighs enormously the trade of France with all French colonies. France is to-day a better colony for the Germans than they could make of any exotic colony which France owns.

“They tell me,” said a French Deputy recently (in a not quite original mot), “that the Germans are at Agadir. I know they are in the Champs-Elysees.” Which, of course, is in reality a much more serious matter.

And those Frenchmen who regret this disappearance of their race, and declare that the energy and blood and money which is now poured out so lavishly in Africa and in Asia ought to be diverted to its arrest, to the colonization and development of France by better social, industrial, commercial, and political organization, to the resisting of the exploitation of the mother country by inflowing masses of foreigners, are declared to be bad patriots, dead to the sentiment of the flag, dead to the call of the bugle, are silenced in fact by a fustian as senseless and mischievous as that which in some marvelous way the politician, hypnotized by the old formulae, has managed to make pass as “patriotism” in most countries.

| Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.