It was on the twelfth of March, 1613, that the “Mayflower” of the Jesuits sailed from Honfleur for the shores of New England. Enter La Saussaye.

Public domain image from “Wikipedia.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

First we conclude Chapter 6.

Previously on Parkman

The dark months wore slowly on. A band of half-famished men gathered about the huge fires of their barn-like hall, moody, sullen, and quarrelsome. Discord was here in the black robe of the Jesuit and the brown capote of the rival trader. The position of the wretched little colony may well provoke reflection. Here lay the shaggy continent, from Florida to the Pole, outstretched in savage slumber along the sea, the stern domain of Nature, — or, to adopt the ready solution of the Jesuits, a realm of the powers of night, blasted beneath the sceptre of hell. On the banks of James River was a nest of woe-begone Englishmen, a handful of Dutch fur-traders at the mouth of the Hudson, and a few shivering Frenchmen among the snow-drifts of Acadia; while deep within the wild monotony of desolation, on the icy verge of the great northern river, the hand of Champlain upheld the fleur-de-lis on the rock of Quebec. These were the advance guard, the forlorn hope of civilization, messengers of promise to a desert continent. Yet, unconscious of their high function, not content with inevitable woes, they were rent by petty jealousies and miserable feuds; while each of these detached fragments of rival nationalities, scarcely able to maintain its own wretched existence on a few square miles, begrudged to the others the smallest share in a domain which all the nations of Europe could hardly have sufficed to fill.

One evening, as the forlorn tenants of Port Royal sat together disconsolate, Biard was seized with a spirit of prophecy. He called upon Biencourt to serve out the little of wine that remained, — a proposal which met with high favor from the company present, though apparently with none from the youthful Vice-Admiral. The wine was ordered, however, and, as an unwonted cheer ran round the circle, the Jesuit announced that an inward voice told him how, within a month, they should see a ship from France. In truth, they saw one within a week. On the twentythird of January, 1612, arrived a small vessel laden with a moderate store of provisions and abundant seeds of future strife.

This was the expected succor sent by Poutrincourt. A series of ruinous voyages had exhausted his resources but he had staked all on the success of the colony, had even brought his family to Acadia, and he would not leave them and his companions to perish. His credit was gone; his hopes were dashed; yet assistance was proffered, and, in his extremity, he was forced to accept it. It came from Madame de Guercheville and her Jesuit advisers. She offered to buy the interest of a thousand crowns in the enterprise. The ill-omened succor could not be refused; but this was not all. The zealous protectress of the missions obtained from De Monts, whose fortunes, like those of Poutrincouirt, had ebbed low, a transfer of all his claims to the lands of Acadia; while the young King, Louis the Thirteenth, was persuaded to give her, in addition, a new grant of all the territory of North America, from the St. Lawrence to Florida. Thus did Madame de Guercheville, or in other words, the Jesuits who used her name as a cover, become proprietors of the greater part of the future United States and British Provinces. The English colony of Virginia and the Dutch trading-houses of New York were included within the limits of this destined Northern Paraguay; while Port Royal, the seigniory of the unfortunate Poutrincourt, was encompassed, like a petty island, by the vast domain of the Society of Jesus. They could not deprive him of it, since his title had been confirmed by the late King, but they flattered themselves, to borrow their own language, that he would be “confined as in a prison.” His grant, however, had been vaguely worded, and, while they held him restricted to an insignificant patch of ground, he claimed lordship over a wide and indefinite territory. Here was argument for endless strife. Other interests, too, were adverse. Poutrincourt, in his discouragement, had abandoned his plan of liberal colonization, and now thought of nothing but beaver-skins. He wished to make a trading-post; the Jesuits wished to make a mission.

When the vessel anchored before Port Royal, Biencourt, with disgust and anger, saw another Jesuit landed at the pier. This was Gilbert du Thet, a lay brother, versed in affairs of this world, who had come out as representative and administrator of Madame de Guercheville. Poutrincourt, also, had his agent on board; and, without the loss of a day, the two began to quarrel. A truce ensued; then a smothered feud, pervading the whole colony, and ending in a notable explosion. The Jesuits, chafing under the sway of Biencourt, had withdrawn without ceremony, and betaken themselves to the vessel, intending to sail for France. Biencourt, exasperated at such a breach of discipline, and fearing their representations at court, ordered them to return, adding that, since the Queen had commended them to his especial care, he could not, in conscience, lose sight of them. The indignant fathers excommunicated him. On this, the sagamore Louis, son of the grisly convert Membertou, begged leave to kill them; but Biencourt would not countenance this summary mode of relieving his embarrassment. He again, in the King’s name, ordered the clerical mutineers to return to the fort. Biard declared that he would not, threatened to excommunicate any who should lay hand on him, and called the Vice-Admiral a robber. His wrath, however, soon cooled; he yielded to necessity, and came quietly ashore, where, for the next three months, neither he nor his colleagues would say mass, or perform any office of religion. At length a change came over him; he made advances of peace, prayed that the past might be forgotten, said mass again, and closed with a petition that Brother du Thet might be allowed to go to France in a trading vessel then on the coast. His petition being granted, he wrote to Poutrincourt a letter overflowing with praises of his son; and, charged with this missive, Du Thet set sail.

Pending these squabbles, the Jesuits at home were far from idle. Bent on ridding themselves of Poutrincourt, they seized, in satisfaction of debts due them, all the cargo of his returning vessel, and involved him in a network of litigation. If we accept his own statements in a letter to his friend Lescarbot, he was outrageously misused, and indeed defrauded, by his clerical copartners, who at length had him thrown into prison. Here, exasperated, weary, sick of Acadia, and anxious for the wretched exiles who looked to him for succor, the unfortunate man fell ill. Regaining his liberty, he again addressed himself with what strength remained to the forlorn task of sending relief to his son and his comrades.

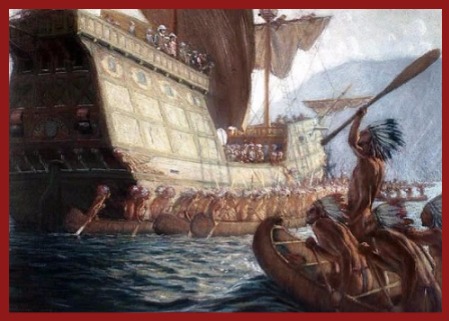

Scarcely had Brother Gilbert du Thet arrived in France, when Madame de Guercheville and her Jesuits, strong in court favor and in the charity of wealthy penitents, prepared to take possession of their empire beyond sea. Contributions were asked, and not in vain; for the sagacious fathers, mindful of every spring of influence, had deeply studied the mazes of feminine psychology, and then, as now, were favorite confessors of the fair. It was on the twelfth of March, 1613, that the “Mayflower” of the Jesuits sailed from Honfleur for the shores of New England. She was the “Jonas,” formerly in the service of De Monts, a small craft bearing forty-eight sailors and colonists, including two Jesuits, Father Quentin and Brother Du Thet. She carried horses, too, and goats, and was abundantly stored with all things needful by the pious munificence of her patrons. A courtier named La Saussaye was chief of the colony, Captain Charles Fleury commanded the ship, and, as she winged her way across the Atlantic, benedictions hovered over her from lordly halls and perfumed chambers.

On the sixteenth of May, La Saussaye touched at La Heve, where he heard mass, planted a cross, and displayed the scutcheon of Madame de Guercheville. Thence, passing on to Port Royal, he found Biard, Masse, their servant-boy, an apothecary, and one man beside. Biencourt and his followers were scattered about the woods and shores, digging the tuberous roots called ground-nuts, catching alewives in the brooks, and by similar expedients sustaining their miserable existence. Taking the two Jesuits on board, the voyagers steered for the Penobscot.

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

A fog rose upon the sea. They sailed to and fro, groping their way in blindness, straining their eyes through the mist, and trembling each instant lest they should descry the black outline of some deadly reef and the ghostly death-dance of the breakers, But Heaven heard their prayers. At night they could see the stars. The sun rose resplendent on a laughing sea, and his morning beams streamed fair and full on the wild heights of the island of Mount Desert. They entered a bay that stretched inland between iron-bound shores, and gave it the name of St. Sauveur. It is now called Frenchman’s Bay. They saw a coast-line of weather-beaten crags set thick with spruce and fir, the surf-washed cliffs of Great Head and Schooner Head, the rocky front of Newport Mountain, patched with ragged woods, the arid domes of Dry Mountain and Green Mountain, the round bristly backs of the Porcupine Islands, and the waving outline of the Gouldsborough Hills.

La Saussaye cast anchor not far from Schooner Head, and here he lay till evening. The jet-black shade betwixt crags and sea, the pines along the cliff, pencilled against the fiery sunset, the dreamy slumber of distant mountains bathed in shadowy purples — such is the scene that in this our day greets the wandering artist, the roving collegian bivouacked on the shore, or the pilgrim from stifled cities renewing his laded strength in the mighty life of Nature. Perhaps they then greeted the adventurous Frenchmen. There was peace on the wilderness and peace on the sea; but none in this missionary bark, pioneer of Christianity and civilization. A rabble of angry sailors clamored on her deck, ready to mutiny over the terms of their engagement. Should the time of their stay be reckoned from their landing at La Heve, or from their anchoring at Mount Desert? Fleury, the naval commander, took their part. Sailor, courtier, and priest gave tongue together in vociferous debate. Poutrincourt was far away, a ruined man, and the intractable Vice-Admiral had ceased from troubling; yet not the less were the omens of the pious enterprise sinister and dark. The company, however, went ashore, raised a cross, and heard mass.

At a distance in the woods they saw the signal smoke of Indians, whom Biard lost no time in visiting. Some of them were from a village on the shore, three leagues westward. They urged the French to go with them to their wigwams. The astute savages had learned already how to deal with a Jesuit.

“Our great chief, Asticou, is there. He wishes for baptism. He is very sick. He will die unbaptized. He will burn in hell, and it will be all your fault.”

This was enough. Biard embarked in a canoe, and they paddied him to the spot, where he found the great chief, Asticou, in his wigwam, with a heavy cold in the head. Disappointed of his charitable purpose, the priest consoled himself with observing the beauties of the neighboring shore, which seemed to him better fitted than St. Sauveur for the intended settlement. It was a gentle slope, descending to the water, covered with tall grass, and backed by rocky hills. It looked southeast upon a harbor where a fleet might ride at anchor, sheltered from the gales by a cluster of islands.

– Pioneers of France in the New World Part II, Chapter 7 by Francis Parkman

So the La Saussaye story.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Introduction.

If, at times, it may seem that range has been allowed to fancy, it is so in appearance only; since the minutest details of narrative or description rest on authentic documents or on personal observation.

Faithfulness to the truth of history involves far more than a research, however patient and scrupulous, into special facts. Such facts may be detailed with the most minute exactness, and yet the narrative, taken as a whole, may be unmeaning or untrue. The narrator must seek to imbue himself with the life and spirit of the time. He must study events in their bearings near and remote; in the character, habits, and manners of those who took part in them, he must himself be, as it were, a sharer or a spectator of the action he describes.

With respect to that special research which, if inadequate, is still in the most emphatic sense indispensable, it has been the writer’s aim to exhaust the existing material of every subject treated. While it would be folly to claim success in such an attempt, he has reason to hope that, so far at least as relates to the present volume, nothing of much importance has escaped him. With respect to the general preparation just alluded to, he has long been too fond of his theme to neglect any means within his reach of making his conception of it distinct and true.

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

Here is a Kindle version: Complete Works for just $2.

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Biography of Samuel de Champlain.

- Article on New France in North America.

- From the Canada History Project.

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.