Experiments to date seem to establish that the connective tissue, at any rate, is “immortal.”

Alexis Carrel Transplants Blood Vessels and Organs, our series on early twentieth century advances in the life sciences published shortly after Alexis Carrel won the Noble Prize his work on vascular suture and the transplantation of blood vessels and organs in 1912.

Previously in Alexis Carrel Transplants Blood Vessels and Organs.

Time: 1912

Public domain image from Wikipedia .

The “Immortality” of Tissues (continued)

By Genevieve Grandcourt

The following summary of this interesting and vitally important and epoch-making work of Carrel is translated from an article published in Paris recently by Professor Pozzi, who witnessed the experiments:

“Carrel found that the pulsations of a fragment of heart, which had diminished in number and intensity or ceased, could be revived to the normal state by a washing and a passage. In a secondary culture, two fragments of heart, separated by a free space, beat as strongly and regularly. The larger fragment contracted 92 times a minute and the smaller 120 times. For three days, the number and intensity of the pulsations varied slightly. On the fourth day, the pulsations diminished considerably in intensity. The large fragment beat 40 times a minute and the little fragment 90 times. The culture was washed and placed in a new medium. An hour and a half after, the pulsations had become very strong. The large fragment contracted 120 times a minute and the small fragment 160 times. At the same time the fragments grew rapidly. At the end of eight hours they were united and formed a mass of which all the parts beat synchronically.”

Experiments to date seem to establish that the connective tissue, at any rate, is “immortal.”

From this research, it is possible to arrive at certain logical conclusions, which, however, it remains for the future to confirm. One, and the most important, is that the normal circulation of the blood does not succeed in freeing all the waste products of the tissues, and that this is the cause of senility and death. Were science to find some way to wash the tissues in the living organism as they have been washed in these cultures, man’s life might be indefinitely prolonged.

By R. Legendre

The Nobel prize in medicine for 1912 has just been awarded to Dr. Alexis Carrel, a Frenchman, of Lyon, now employed at the Rockefeller Institute of New York, for his entire work relating to the suture of vessels and the transplantation of organs.

The remarkable results obtained in these fields by various experimenters, of whom Carrel is most widely known, and also the wonderful applications made of them by certain surgeons have already been widely published.

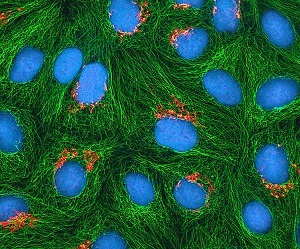

The journals have frequently spoken lately of “cultures” of tissues detached from the organism to which they belonged; and some of them, exaggerating the results already obtained, have stated that it is now possible to make living tissues grow and increase when so detached.

Having given these subjects much study I wish to state here what has already been done and what we may hope to accomplish. As a matter of fact we do not yet know how to construct living cells; the forms obtained with mineral substances by Errera, Stephane Leduc, and others, have only a remote resemblance to those of life; neither do we know how to prevent death; but yet it is interesting to know that it is possible to prolong for some time the life of organs, tissues, and cells after they have been removed from the organism.

The idea of preserving the life of greater or lesser parts of an organism occurred at about the same time to a number of persons, and though the ends in view have been quite different, the investigations have led to essentially similar results. The surgeons who for a long time have transplanted various organs and grafted different tissues, bits of skin among others, have sought to prolong the period during which the grafts may be preserved alive from the time they are taken from the parent individual until they are implanted either upon the same subject or upon another. The physiologists have attempted to isolate certain organs and preserve them alive for some time in order to simplify their experiments by suppressing the complex action of the nervous system and of glands which often render difficult a proper interpretation of the experiments. The cytologists have tried to preserve cells alive outside the organism in more simple and well-defined conditions. These various efforts have already given, as we shall see, very excellent results both as regards the theoretical knowledge of vital phenomena and for the practice of surgery.

It has been possible to preserve for more or less time many organs in a living condition when detached from the organism. The organ first tried and which has been most frequently and completely investigated is the heart. This is because of its resistance to any arrest of the circulation and also because its survival is easily shown by its contractility. In man the heart has been seen to beat spontaneously and completely 25 minutes after a legal decapitation (Renard and Loye, 1887), and by massage of the organ its beating may be restored after it has been arrested for 40 minutes (Rehn, 1909). By irrigation of the heart and especially of its coronary vessels the period of revival may be much prolonged.

The first experiments with artificial circulation in the isolated heart were made in Ludwig’s laboratory, but they were limited to the frog and the inferior vertebrates. Since then experiments on the survival of the heart have multiplied and become classic. Artificial circulation has kept the heart of man contracting normally for 20 hours (Kuliabko, 1902), that of the monkey for 54 hours (Hering, 1903), that of the rabbit for 5 days (Kuliabko, 1902), etc. It has also enabled us to study the influence upon the heart of physical factors, such as temperature, isotonia; chemical factors, such as various salts and the different ions; and even complex pharmaceutical products. Kuliabko (1902) was even able to note contractions in the heart of a rabbit that had been kept in cold storage for 18 hours, and in the heart of a cat similarly kept after 24 hours.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.