Today’s installment concludes The Decemvirate In Rome,

our selection from A History of Rome by Henry G. Liddell published in 1855. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of four thousand words. Congratulations!

Previously in The Decemvirate In Rome.

Time: 448 BC

Place: City of Rome

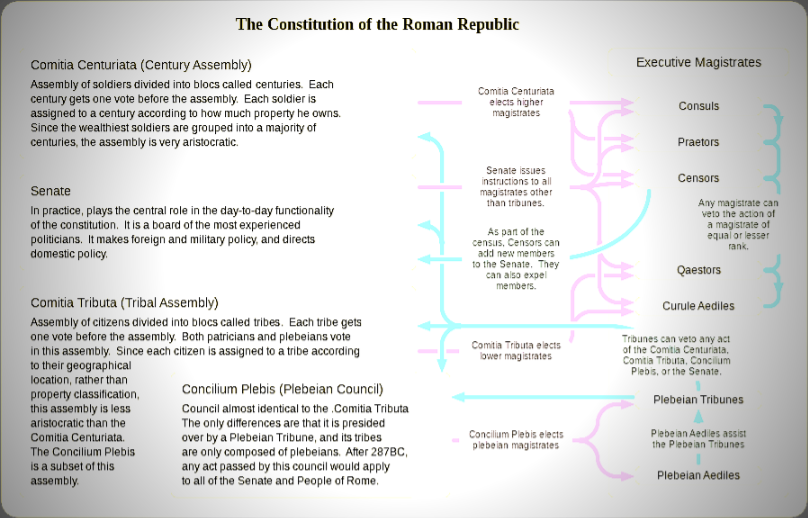

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

Next morning, early, Virginius entered the Forum, leading his daughter by the hand, both clad in mean attire. A great number of friends and matrons attended him, and he went about among the people entreating them to support him against the tyranny of Appius. So when Appius came to take his place on the judgment seat he found the Forum full of people, all friendly to Virginius and his cause. But he inherited the boldness as well as the vices of his sires, and though he saw Virginius standing there ready to prove that he was the maiden’s father, he at once gave judgment, against his own law, that Virginia should be given up to M. Claudius till it should be proved that she was free. The wretch came up to seize her, and the lictors kept the people from him. Virginius, now despairing of deliverance, begged Appius to allow him to ask the maiden whether she was indeed his daughter or not. “If,” said he, “I find I am not her father, I shall bear her loss the lighter.” Under this pretence he drew her aside to a spot upon the northern side of the Forum, afterward called the “Nova Tabernce” and here, snatching up a knife from a butcher’s stall, he cried: “In this way only can I keep thee free!” —- and so saying, stabbed her to the heart. Then he turned to the tribunal and said, “On thee, Appius, and on thy head be this blood!” Appius cried out to seize “the murderer,” but the crowd made way for Virginius, and he passed through them holding up the bloody knife, and went out at the gate and made straight for the army. There, when the soldiers had heard his tale, they at once abandoned their decemviral generals and marched to Rome. They were soon followed by the other army from the Sabine frontier; for to them Icilius had gone, and Numitorius; and they found willing ears among men who were already enraged by the murder of old Siccius Dentatus. So the two armies joined their banners, elected new generals, and encamped upon the Aventine hill, the quarter of the plebeians.

Meantime the people at home had risen against Appius, and after driving him from the Forum they joined their armed fellow — citizens upon the Aventine. There the whole body of the commons, armed and unarmed, hung like a dark cloud ready to burst upon the city.

Whatever may be the truth of the legends of Siccius and Virginia, there can be no doubt that the conduct of the decemvirs had brought matters to the verge of civil war. At this juncture the senate met, and the moderate party so far prevailed as to send their own leaders, M. Horatius Barbatus and L. Valerius Potitus, to negotiate with the insurgents. The plebeians were ready to listen to the voices of these men; for they remembered that the consuls of the first year of the Republic, when the patrician burgesses were friends to the plebeians, were named Valerius and Horatius; and so they appointed M. Duillius, a former tribune, to be their spokesman. But no good came of it; and Duillius persuaded the plebeians to leave the city, and once more to occupy the Sacred Mount.

Then remembrances of the great secession came back upon the minds of the patricians, and the senate, observing the calm and resolute bearing of the plebeian leaders, compelled the decemvirs to resign, and sent back Valerius and Horatius to negotiate anew.

The leaders of the plebeians demanded: First, that the tribuneship should be restored, and the Comitia Tributa recognized; secondly, that a right of appeal to the people against the power of the supreme magistrate should be secured; thirdly, that full indemnity should be granted to the movers and promoters of the late secession; fourthly, that the decemvirs should be burnt alive.

Of these demands the deputies of the senate agreed to the three first; but the fourth, they said, was unworthy of a free people; it was a piece of tyranny, as bad as any of the worst acts of the late government; and it was needless, because anyone who had reason of complaint against the late decemvirs might proceed against them according to law. The plebeians listened to these words of wisdom, and withdrew their savage demand. The other three were confirmed by the fathers, and the plebeians returned to their quarters on the Aventine. Here they held an assembly according to their tribes, in which the pontifex Maximus presided; and they now, for the first time, elected ten tribunes —- first Virginius, Numitorius, and Icilius, then Duillius and six others: so full were their minds of the wrong done to the daughter of Virginius; so entirely was it the blood of young Virginia that overthrew the decemvirs, even as that of Lucretia had driven out the Tarquins.

The plebeians had now returned to the city, headed by their ten tribunes, a number which was never again altered so long as the tribunate continued in existence. It remained for the patricians to redeem the pledges given by their agents Valerius and Horatius on the other demands of the plebeian leaders.

The first thing to settle was the election of the supreme magistrates. The decemvirs had fallen, and the state was without any executive government.

It has been supposed, as we have said above, that the government of the decemvirs was intended to be perpetual. The patricians gave up their consuls, and the plebeians their tribunes, on condition that each order was to be admitted to an equal share in the new decemviral college. But the tribunes were now restored in augmented number, and it was but natural that the patricians should insist on again occupying all places in the supreme magistracy. By common consent, as it would seem, the Comitia of the Centuries met and elected to the consulate the two patricians who had shown themselves the friends of both orders: L. Valerius Potitus and M. Horatius Barbatus. Thus ended the government of the decemvirate.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on The Decemvirate In Rome by Henry G. Liddell from his book A History of Rome published in 1855. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on The Decemvirate In Rome here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.