Port Royal was a quadrangle of wooden buildings, enclosing a spacious court. This was Port Royal’s first winter.

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously on Parkman

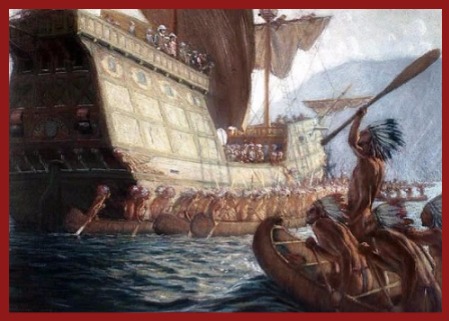

It was noon on the twenty-seventh [of May, 1606 – jl] when the “Jonas” passed the rocky gateway of Port Royal Basin, and Lescarbot gazed with delight and wonder on the calm expanse of sunny waters, with its amphitheatre of woody hills, wherein he saw the future asylum of distressed merit and impoverished industry. Slowly, before a favoring breeze, they held their course towards the head of the harbor, which narrowed as they advanced; but all was solitude, — no moving sail, no sign of human presence. At length, on their left, nestling in deep forests, they saw the wooden walls and roofs of the infant colony. Then appeared a birch canoe, cautiously coming towards them, guided by an old Indian. Then a Frenchman, arquebuse in hand, came down to the shore; and then, from the wooden bastion, sprang the smoke of a saluting shot. The ship replied; the trumpets lent their voices to the din, and the forests and the hills gave back unwonted echoes. The voyagers landed, and found the colony of Port Royal dwindled to two solitary Frenchmen.

These soon told their story. The preceding winter had been one of much suffering, though by no means the counterpart of the woeful experience of St. Croix. But when the spring had passed, the summer far advanced, and still no tidings of De Monts had come, Pontgrave grew deeply anxious. To maintain themselves without supplies and succor was impossible. He caused two small vessels to be built, and set out in search of some of the French vessels on the fishing stations. This was but twelve days before the arrival of the ship “Jonas.” Two men had bravely offered themselves to stay behind and guard the buildings, guns, and munitions; and an old Indian chief, named Memberton, a fast friend of the French, and still a redoubted warrior, we are told, though reputed to number more than a hundred years, proved a stanch ally. When the ship approached, the two guardians were at dinner in their room at the fort. Memberton, always on the watch, saw the advancing sail, and, shouting from the gate, roused them from their repast. In doubt who the new-comers might be, one ran to the shore with his gun, while the other repaired to the platform where four cannon were mounted, in the valorous resolve to show fight should the strangers prove to be enemies. Happily this redundancy of mettle proved needless. He saw the white flag fluttering at the masthead, and joyfully fired his pieces as a salute.

The voyagers landed, and eagerly surveyed their new home. Some wandered through the buildings; some visited the cluster of Indian wigwams hard by; some roamed in the forest and over the meadows that bordered the neighboring river. The deserted fort now swarmed with life; and, the better to celebrate their prosperous arrival, Poutrincourt placed a hogs-head of wine in the courtyard at the discretion of his followers, whose hilarity, in consequence, became exuberant. Nor was it diminished when Pontgrave’s vessels were seen entering the harbor. A boat sent by Pountrincourt, more than a week before, to explore the coasts, had met them near Cape Sable, and they joyfully returned to Port Royal.

Pontgrave, however, soon sailed for France in the “Jonas,” hoping on his way to seize certain contraband fur-traders, reported to be at Canseau and Cape Breton. Poutrincourt and Champlain, bent on finding a better site for their settlement in a more southern latitude, set out on a voyage of discovery, in an ill-built vessel of eighteen tons, while Lescarbot remained in charge of Port Royal. They had little for their pains but danger, hardship, and mishap. The autumn gales cut short their exploration; and, after visiting Gloucester Harbor, doubling Monoinoy Point, and advancing as far as the neighborhood of Hyannis, on the southeast coast of Massachusetts, they turned back, somewhat disgusted with their errand. Along the eastern verge of Cape Cod they found the shore thickly studded with the wigwams of a race who were less hunters than tillers of the soil. At Chatham Harbor — called by them Port Fortune — five of the company, who, contrary to orders, had remained on shore all night, were assailed, as they slept around their fire, by a shower of arrows from four hundred Indians. Two were killed outright, while the survivors fled for their boat, bristling like porcupines with the feathered missiles, — a scene oddly portrayed by the untutored pencil of Champlain. He and Poutrincourt, with eight men, hearing the war-whoops and the cries for aid, sprang up from sleep, snatched their weapons, pulled ashore in their shirts, and charged the yelling multitude, who fled before their spectral assailants, and vanished in the woods. “Thus,” observes Lescarbot, “did thirty-five thousand Midianites fly before Gideon and his three hundred.” The French buried their dead comrades; but, as they chanted their funeral hymn, the Indians, at a safe distance on a neighboring hill, were dancing in glee and triumph, and mocking them with unseemly gestures; and no sooner had the party re-embarked, than they dug up the dead bodies, burnt them, and arrayed themselves in their shirts. Little pleased with the country or its inhabitants, the voyagers turned their prow towards Port Royal, though not until, by a treacherous device, they had lured some of their late assailants within their reach, killed them, and cut off their heads as trophies. Near Mount Desert, on a stormy night, their rudder broke, and they had a hair-breadth escape from destruction. The chief object of their voyage, that of discovering a site for their colony under a more southern sky, had failed. Pontgrave’s son had his hand blown off by the bursting of his gun; several of their number had been killed; others were sick or wounded; and thus, on the fourteenth of November, with somewhat downcast visages, they guided their helpless vessel with a pair of oars to the landing at Port Royal.

“I will not,” says Lescarbot, “compare their perils to those of Ulysses, nor yet of Aeneas, lest thereby I should sully our holy enterprise with things impure.”

He and his followers had been expecting them with great anxiety. His alert and buoyant spirit had conceived a plan for enlivening the courage of the company, a little dashed of late by misgivings and forebodings. Accordingly, as Poutrincourt, Champlain, and their weather-beaten crew approached the wooden gateway of Port Royal, Neptune issued forth, followed by his tritons, who greeted the voyagers in good French verse, written in all haste for the occasion by Lescarbot. And, as they entered, they beheld, blazoned over the arch, the arms of Prance, circled with laurels, and flanked by the scuteheons of De Monts and Poutrincourt.

The ingenious author of these devices had busied himself, during the absence of his associates, in more serious labors for the welfare of the colony. He explored the low borders of the river Equille, or Annapolis. Here, in the solitude, he saw great meadows, where the moose, with their young, were grazing, and where at times the rank grass was beaten to a pulp by the trampling of their hoofs. He burned the grass, and sowed crops of wheat, rye, and barley in its stead. His appearance gave so little promise of personal vigor, that some of the party assured him that he would never see France again, and warned him to husband his strength; but he knew himself better, and set at naught these comforting monitions. He was the most diligent of workers.

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

He made gardens near the fort, where, in his zeal, he plied the hoe with his own hands late into the moonlight evenings. The priests, of whom at the outset there had been no lack, had all succumbed to the scurvy at St. Croix; and Lescarbot, so far as a layman might, essayed to supply their place, reading on Sundays from the Scriptures, and adding expositions of his own after a fashion not remarkable for rigorous Catholicity. Of an evening, when not engrossed with his garden, he was reading or writing in his room, perhaps preparing the material of that History of New France in which, despite the versatility of his busy brain, his good sense and capacity are clearly made manifest.

Now, however, when the whole company were reassembled, Lescarbot found associates more congenial than the rude soldiers, mechanics, and laborers who gathered at night around the blazing logs in their rude hall. Port Royal was a quadrangle of wooden buildings, enclosing a spacious court. At the southeast corner was the arched gateway, whence a path, a few paces in length, led to the water. It was flanked by a sort of bastion of palisades, while at the southwest corner was another bastion, on which four cannon were mounted. On the east side of the quadrangle was a range of magazines and storehouses; on the west were quarters for the men; on the north, a dining-hall and lodgings for the principal persons of the company; while on the south, or water side, were the kitchen, the forge, and the oven. Except the Garden-patches and the cemetery, the adjacent ground was thickly studded with the Stumps of the newly felled trees.

Most bountiful provision had been made for the temporal wants of the colonists, and Lescarbot is profuse in praise of the liberality of Du Monte and two merchants of Rochelle, who had freighted the ship “Jonas.” Of wine, in particular, the supply was so generous, that every man in Port Royal was served with three pints daily.

The principal persons of the colony sat, fifteen in number, at Poutrincourt’s table, which, by an ingenious device of Champlain, was always well furnished. He formed the fifteen into a new order, christened “L’Ordre de Bon-Temps.” Each was Grand Master in turn, holding office for one day. It was his function to cater for the company; and, as it became a point of honor to fill the post with credit, the prospective Grand Master was usually busy, for several days before coming to his dignity, in hunting, fishing, or bartering provisions with the Indians. Thus did Poutrincourt’s table groan beneath all the luxuries of the winter forest, — flesh of moose, caribou, and deer, beaver, otter, and hare, bears and wild-cats; with ducks, geese, grouse, and plover; sturgeon, too, and trout, and fish innumerable, speared through the ice of the Equille, or drawn from the depths of the neighboring bay. “And,” says Lescarbot, in closing his bill of fare, “whatever our gourmands at home may think, we found as good cheer at Port Royal as they at their Rue aux Ours in Paris, and that, too, at a cheaper rate.” For the preparation of this manifold provision, the Grand Master was also answerable; since, during his day of office, he was autocrat of the kitchen.

Nor did this bounteous repast lack a solemn and befitting ceremonial. When the hour had struck, after the manner of our fathers they dined at noon, the Grand Master entered the hall, a napkin on his shoulder, his staff of office in his hand, and the collar of the Order — valued by Lescarbot at four crowns — about his neck. The brotherhood followed, each bearing a dish. The invited guests were Indian chiefs, of whom old Memberton was daily present, seated at table with the French, who took pleasure in this red-skin companionship. Those of humbler degree, warriors, squaws, and children, sat on the floor, or crouched together in the corners of the hall, eagerly waiting their portion of biscuit or of bread, a novel and much coveted luxury. Being always treated with kindness, they became fond of the French, who often followed them on their moose-hunts, and shared their winter bivouac.

At the evening meal there was less of form and circumstance; and when the winter night closed in, when the flame crackled and the sparks streamed up the wide-throated chimney, and the founders of New France with their tawny allies were gathered around the blaze, then did the Grand Master resign the collar and the staff to the successor of his honors, and, with jovial courtesy, pledge him in a cup of wine. Thus these ingenious Frenchmen beguiled the winter of their exile.

– Pioneers of France in the New World Part II, Chapter 4 by Francis Parkman

This was Port Royal’s first winter.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Introduction.

If, at times, it may seem that range has been allowed to fancy, it is so in appearance only; since the minutest details of narrative or description rest on authentic documents or on personal observation.

Faithfulness to the truth of history involves far more than a research, however patient and scrupulous, into special facts. Such facts may be detailed with the most minute exactness, and yet the narrative, taken as a whole, may be unmeaning or untrue. The narrator must seek to imbue himself with the life and spirit of the time. He must study events in their bearings near and remote; in the character, habits, and manners of those who took part in them, he must himself be, as it were, a sharer or a spectator of the action he describes.

With respect to that special research which, if inadequate, is still in the most emphatic sense indispensable, it has been the writer’s aim to exhaust the existing material of every subject treated. While it would be folly to claim success in such an attempt, he has reason to hope that, so far at least as relates to the present volume, nothing of much importance has escaped him. With respect to the general preparation just alluded to, he has long been too fond of his theme to neglect any means within his reach of making his conception of it distinct and true.

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

Here is a Kindle version: Complete Works for just $2.

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Biography of Samuel de Champlain.

- Article on New France in North America.

- From the Canada History Project.

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.