Champlain’s most conspicuous merit lies in the light that he threw into the dark places of American geography, and the order that he brought out of the chaos of American cartography. Today’s passage links the names of two great explorers: Champlain Lescarbot.

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

First we conclude Chapter 3.

Previously on Parkman

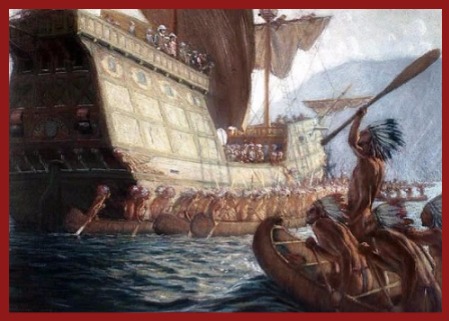

Weary of St. Croix, De Monts resolved to seek out a more auspicious site, on which to rear the capital of his wilderness dominion. During the preceding September, Champlain had ranged the westward coast in a pinnace, visited and named the island of Mount Desert, and entered the mouth of the river Penobscot, called by him the Pemetigoet, or Pentegoet, and previously known to fur-traders and fishermen as the Norembega, a name which it shared with all the adjacent region. Now, embarking a second time, in a bark of fifteen tons, with De Monts, several gentlemen, twenty sailors, and an Indian with his squaw, he set forth on the eighteenth of June on a second voyage of discovery. They coasted the strangely indented shores of Maine, with its reefs and surf-washed islands, rocky headlands, and deep embosomed bays, passed Mount Desert and the Penobscot, explored the mouths of the Kennebec, crossed Casco Bay, and descried the distant peaks of the White Mountains. The ninth of July [1604 -jl] brought them to Saco Bay. They were now within the limits of a group of tribes who were called by the French the Armouchiquois, and who included those whom the English afterwards called the Massachusetts. They differed in habits as well as in language from the Etechemins and Miemacs of Acadia, for they were tillers of the soil, and around their wigwams were fields of maize, beans, pumpkins, squashes, tobacco, and the so-called Jerusalem artichoke. Near Pront’s Neck, more than eighty of them ran down to the shore to meet the strangers, dancing and yelping to show their joy. They had a fort of palisades on a rising ground by the Saco, for they were at deadly war with their neighbors towards the east.

On the twelfth, the French resumed their voyage, and, like some adventurous party of pleasure, held their course by the beaches of York and Wells, Portsmouth Harbor, the Isles of Shoals, Rye Beach, and Hampton Beach, till, on the fifteenth, they descried the dim outline of Cape Ann. Champlain called it Cap aux Isles, from the three adjacent islands, and in a subsequent voyage he gave the name of Beauport to the neighboring harbor of Gloucester. Thence steering southward and westward, they entered Massachusetts Bay, gave the name of Riviere du Guast to a river flowing into it, probably the Charles; passed the islands of Boston Harbor, which Champlain describes as covered with trees, and were met on the way by great numbers of canoes filled with astonished Indians. On Sunday, the seventeenth, they passed Point Allerton and Nantasket Beach, coasted the shores of Cohasset, Scituate, and Marshfield, and anchored for the night near Brant Point. On the morning of the eighteenth, a head wind forced them to take shelter in Port St. Louis, for so they called the harbor of Plymouth, where the Pilgrims made their memorable landing fifteen years later. Indian wigwams and garden patches lined the shore. A troop of the inhabitants came down to the beach and danced; while others, who had been fishing, approached in their canoes, came on board the vessel, and showed Champlain their fish-hooks, consisting of a barbed bone lashed at an acute angle to a slip of wood.

From Plymouth the party circled round the bay, doubled Cape Cod, called by Champlain Cap Blanc, from its glistening white sands, and steered southward to Nausett Harbor, which, by reason of its shoals and sand-bars, they named Port Mallebarre. Here their prosperity deserted them. A party of sailors went behind the sand-banks to find fresh water at a spring, when an Indian snatched a kettle from one of them, and its owner, pursuing, fell, pierced with arrows by the robber’s comrades. The French in the vessel opened fire. Champlain’s arquebuse burst, and was near killing him, while the Indians, swift as deer, quickly gained the woods. Several of the tribe chanced to be on board the vessel, but flung themselves with such alacrity into the water that only one was caught. They bound him hand and foot, but soon after humanely set him at liberty.

Champlain, who we are told “delighted marvelously in these enterprises,” had busied himself throughout the voyage with taking observations, making charts, and studying the wonders of land and sea. The “horse-foot crab” seems to have awakened his special curiosity, and he describes it with amusing exactness. Of the human tenants of the New England coast he has also left the first precise and trustworthy account. They were clearly more numerous than when the Puritans landed at Plymouth, since in the interval a pestilence made great havoc among them. But Champlain’s most conspicuous merit lies in the light that he threw into the dark places of American geography, and the order that he brought out of the chaos of American cartography; for it was a result of this and the rest of his voyages that precision and clearness began at last to supplant the vagueness, confusion, and contradiction of the earlier map-makers.

At Nausett Harbor provisions began to fail, and steering for St. Croix the voyagers reached that ill-starred island on the third of August. De Monts had found no spot to his liking. He now bethought him of that inland harbor of Port Royal which he had granted to Poutrincourt, and thither he resolved to remove. Stores, utensils, even portions of the buildings, were placed on board the vessels, carried across the Bay of Fundy, and landed at the chosen spot. It was on the north side of the basin opposite Goat Island, and a little below the mouth of the river Annapolis, called by the French the Equille, and, afterwards, the Dauphin. The axe-men began their task; the dense forest was cleared away, and the buildings of the infant colony soon rose in its place.

But while De Monts and his company were struggling against despair at St. Croix, the enemies of his monopoly were busy at Paris; and, by a ship from France, he was warned that prompt measures were needed to thwart their machinations. Therefore he set sail, leaving Pontgrave to command at Port Royal: while Champlain, Champdore, and others, undaunted by the past, volunteered for a second winter in the wilderness.

Evil reports of a churlish wilderness, a pitiless climate, disease, misery, and death, had heralded the arrival of De Monts. The outlay had been great, the returns small; and when he reached Paris, he found his friends cold, his enemies active and keen. Poutrincourt, however, was still full of zeal; and, though his private affairs urgently called for his presence in France, he resolved, at no small sacrifice, to go in person to Acadia. He had, moreover, a friend who proved an invaluable ally. This was Marc Lescarbot, “avocat en Parlement,” who had been roughly handled by fortune, and was in the mood for such a venture, being desirous, as he tells us, “to fly from a corrupt world,” in which he had just lost a lawsuit. Unlike De Monts, Poutrincourt, and others of his associates, he was not within the pale of the noblesse, belonging to the class of “gens de robe,” which stood at the head of the bourgeoisie, and which, in its higher grades, formed within itself a virtual nobility. Lescarbot was no common man, — not that his abundant gift of verse-making was likely to avail much in the woods of New France, nor yet his classic lore, dashed with a little harmless pedantry, born not of the man, but of the times; but his zeal, his good sense, the vigor of his understanding, and the breadth of his views, were as conspicuous as his quick wit and his lively fancy.

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

One of the best, as well as earliest, records of the early settlement of North America is due to his pen; and it has been said, with a certain degree of truth, that he was no less able to build up a colony than to write its history. He professed himself a Catholic, but his Catholicity sat lightly on him; and he might have passed for one of those amphibious religionists who in the civil wars were called “Les Politiques.”

De Monts and Poutrincourt bestirred themselves to find a priest, since the foes of the enterprise had been loud in lamentation that the spiritual welfare of the Indians had been slighted. But it was Holy Week. All the priests were, or professed to be, busy with exercises and confessions, and not one could be found to undertake the mission of Acadia. They were more successful in engaging mechanics and laborers for the voyage. These were paid a portion of their wages in advance, and were sent in a body to Rochelle, consigned to two merchants of that port, members of the company. De Monts and Poutrincourt went thither by post. Lescarbot soon followed, and no sooner reached Rochelle than he penned and printed his Adieu a la France, a poem which gained for him some credit.

More serious matters awaited him, however, than this dalliance with the Muse. Rochelle was the centre and citadel of Calvinism, — a town of austere and grim aspect, divided, like Cisatlantic communities of later growth, betwixt trade and religion, and, in the interest of both, exacting a deportment of discreet and well-ordered sobriety. “One must walk a strait path here,” says Lescarbot, “unless he would hear from the mayor or the ministers.” But the mechanics sent from Paris, flush of money, and lodged together in the quarter of St. Nicolas, made day and night hideous with riot, and their employers found not a few of them in the hands of the police. Their ship, bearing the inauspicious name of the “Jonas,” lay anchored in the stream, her cargo on board, when a sudden gale blew her adrift. She struck on a pier, then grounded on the flats, bilged, careened, and settled in the mud. Her captain, who was ashore, with Poutrincourt, Lescarbot, and others, hastened aboard, and the pumps were set in motion; while all Rochelle, we are told, came to gaze from the ramparts, with faces of condolence, but at heart well pleased with the disaster. The ship and her cargo were saved, but she must be emptied, repaired, and reladen. Thus a month was lost; at length, on the thirteenth of May, 1606, the disorderly crew were all brought on board, and the “Jonas” put to sea. Poutrincourt and Lescarbot had charge of the expedition, De Monts remaining in France.

Lescarbot describes his emotions at finding himself on an element so deficient in solidity, with only a two-inch plank between him and death. Off the Azores, they spoke a supposed pirate. For the rest, they beguiled the voyage by harpooning porpoises, dancing on deck in calm weather, and fishing for cod on the Grand Bank. They were two months on their way; and when, fevered with eagerness to reach land, they listened hourly for the welcome cry, they were involved in impenetrable fogs. Suddenly the mists parted, the sun shone forth, and streamed fair and bright over the fresh hills and forests of the New World, in near view before them. But the black rocks lay between, lashed by the snow-white breakers.

“Thus,” writes Lescarbot, “doth a man sometimes seek the land as one doth his beloved, who sometimes repulseth her sweetheart very rudely. Finally, upon Saturday, the fifteenth of July, about two o’clock in the afternoon, the sky began to salute us as it were with cannon-shots, shedding tears, as being sorry to have kept us so long in pain;… but, whilst we followed on our course, there came from the land odors incomparable for sweetness, brought with a warm wind so abundantly that all the Orient parts could not produce greater abundance. We did stretch out our hands as it were to take them, so palpable were they, which I have admired a thousand times since.”

– Pioneers of France in the New World Part II, Chapter 4 by Francis Parkman

Champlain Lescarbot and their endeavors.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Introduction.

If, at times, it may seem that range has been allowed to fancy, it is so in appearance only; since the minutest details of narrative or description rest on authentic documents or on personal observation.

Faithfulness to the truth of history involves far more than a research, however patient and scrupulous, into special facts. Such facts may be detailed with the most minute exactness, and yet the narrative, taken as a whole, may be unmeaning or untrue. The narrator must seek to imbue himself with the life and spirit of the time. He must study events in their bearings near and remote; in the character, habits, and manners of those who took part in them, he must himself be, as it were, a sharer or a spectator of the action he describes.

With respect to that special research which, if inadequate, is still in the most emphatic sense indispensable, it has been the writer’s aim to exhaust the existing material of every subject treated. While it would be folly to claim success in such an attempt, he has reason to hope that, so far at least as relates to the present volume, nothing of much importance has escaped him. With respect to the general preparation just alluded to, he has long been too fond of his theme to neglect any means within his reach of making his conception of it distinct and true.

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

Here is a Kindle version: Complete Works for just $2.

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Biography of Samuel de Champlain.

- Article on New France in North America.

- From the Canada History Project.

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.