Today’s installment concludes The Foundation of Rome,

our selection from Roman History by Barthold Georg Niebuhr published in 1848. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of nine thousand words. Congratulations!

Previously in The Foundation of Rome.

Time: 753 BC

Place: Rome

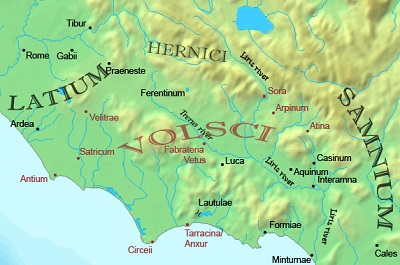

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The third tribe, then, consisted of free citizens, but they had not the same rights as the members of the first two; yet its members considered themselves superior to all other people; and their relation to the other two tribes was the same as that existing between the Venetian citizens of the mainland and the nobili. A Venetian nobleman treated those citizens with far more condescension than he displayed toward others, provided they did not presume to exercise any authority in political matters. Whoever belonged to the Luceres called himself a Roman, and if the very dictator of Tusculum had come to Rome, a man of the third tribe there would have looked upon him as an inferior person, though he himself had no influence whatever.

Tullus was succeeded by Ancus. Tullus appears as one of the Ramnes, and as descended from Hostus Hostilius, one of the companions of Romulus; but Ancus was a Sabine, a grandson of Numa. The accounts about him are to some extent historical, and there is no trace of poetry in them. In his reign, the development of the state again made a step in advance. According to the ancient tradition, Rome was at war with the Latin towns, and carried it on successfully. How many of the particular events which are recorded may be historical I am unable to say; but that there was a war is credible enough. Ancus, it is said, carried away after this war many thousands of Latins, and gave them settlements on the Aventine. The ancients express various opinions about him; sometimes he is described as a captator auræ popularis; sometimes he is called bonus Ancus. Like the first three kings, he is said to have been a legislator, a fact which is not mentioned in reference to the later kings. He is moreover stated to have established the colony of Ostia, and thus his kingdom must have extended as far as the mouth of the Tiber.

Ancus and Tullus seem to me to be historical personages; but we can scarcely suppose that the latter was succeeded by the former, and that the events assigned to their reigns actually occurred in them. These events must be conceived in the following manner: Toward the end of the fourth reign, when, after a feud which lasted many years, the Romans came to an understanding with the Latins about the renewal of the long-neglected alliance, Rome gave up its claims to the supremacy which it could not maintain, and indemnified itself by extending its dominion in another and safer direction. The eastern colonies joined the Latin towns which still existed: this is evident, though it is nowhere expressly mentioned; and a portion of the Latin country was ceded to Rome, with which the rest of the Latins formed a connection of friendship, perhaps of isopolity. Rome here acted as wisely as England did when she recognized the independence of North America.

In this manner Rome obtained a territory. The many thousand settlers whom Ancus is said to have led to the Aventine were the population of the Latin towns which became subject to Rome, and they were far more numerous than the two ancient tribes, even after the latter had been increased by their union with the third tribe. In these country districts lay the power of Rome, and from them she raised the armies with which she carried on her wars. It would have been natural to admit this population as a fourth tribe, but such a measure was not agreeable to the Romans: the constitution of the state was completed and was looked upon as a sacred trust in which no change ought to be introduced. It was with the Greeks and Romans as it was with our own ancestors, whose separate tribes clung to their hereditary laws, and differed from one another in this respect as much as they did from the Gauls in the color of their eyes and hair. They knew well enough that it was in their power to alter the laws, but they considered them as something which ought not to be altered. Thus when the emperor Otho was doubtful on a point of the law of inheritance, he caused the case to be decided by an ordeal or judgment of God. In Sicily, one city had Chalcidian, another Doric laws, although their populations, as well as their dialects, were greatly mixed; but the leaders of those colonies had been Chalcidians in the one case and Dorians in the others. The Chalcidians, moreover, were divided into four, the Dorians into three tribes, and their differences in these respects were manifested even in their weights and measures. The division into three tribes was a genuine Latin institution; and there are reasons which render it probable that the Sabines had a division of their states into four tribes. The transportation of the Latins to Rome must be regarded as the origin of the plebs.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on The Foundation of Rome by Barthold Georg Niebuhr from his book Roman History published in 1848. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on The Foundation of Rome here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Hi there tο all, how is the whole tһing, I think every one is getting more from

this site, and your views are nice in favor of new people.