It was a scheme of high-sounding promise, but in performance less than contemptible. So the first Canadian colonies failed.

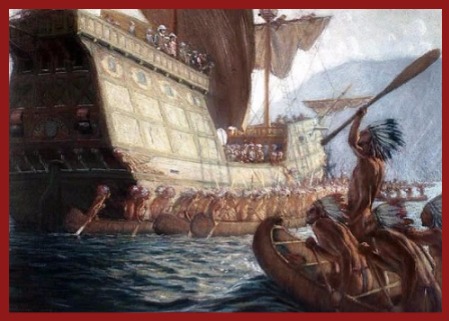

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously on Parkman

Years rolled on. France, long tossed among the surges of civil commotion, plunged at last into a gulf of fratricidal war. Blazing hamlets, sacked cities, fields steaming with slaughter, profaned altars, and ravished maidens, marked the track of the tornado. There was little room for schemes of foreign enterprise. Yet, far aloof from siege and battle, the fishermen of the western ports still plied their craft on the Banks of Newfoundland. Humanity, morality, decency, might be forgotten, but codfish must still be had for the use of the faithful in Lent and on fast days. Still the wandering Esquimaux saw the Norman and Breton sails hovering around some lonely headland, or anchored in fleets in the harbor of St. John; and still, through salt spray and driving mist, the fishermen dragged up the riches of the sea.

In January and February, 1545, about two vessels a day sailed from French ports for Newfoundland. In 1565, Pedro Menendez complains that the French “rule despotically” in those parts. In 1578, there were a hundred and fifty French fishing-vessels there, besides two hundred of other nations, Spanish, Portuguese, and English. Added to these were twenty or thirty Biscayan whalers. In 1607, there was an old French fisherman at Canseau who had voyaged to these seas for forty-two successive years.

But if the wilderness of ocean had its treasures, so too had the wilderness of woods. It needed but a few knives, beads, and trinkets, and the Indians would throng to the shore burdened with the spoils of their winter hunting. Fishermen threw up their old vocation for the more lucrative trade in bear-skins and beaver-skins. They built rude huts along the shores of Anticosti, where, at that day, the bison, it is said, could be seen wallowing in the sands. They outraged the Indians; they quarrelled with each other; and this infancy of the Canadian fur-trade showed rich promise of the disorders which marked its riper growth. Others, meanwhile, were ranging the gulf in search of walrus tusks; and, the year after the battle of Ivry, St. Malo sent out a fleet of small craft in quest of this new prize.

In all the western seaports, merchants and adventurers turned their eyes towards America; not, like the Spaniards, seeking treasures of silver and gold, but the more modest gains of codfish and train-oil, beaver-skins and marine ivory. St. Malo was conspicuous above them all. The rugged Bretons loved the perils of the sea, and saw with a jealous eye every attempt to shackle their activity on this its favorite field. When in 1588 Jacques Noel and Estienue Chaton — the former a nephew of Cartier and the latter pretending to be so — gained a monopoly of the American fur-trade for twelve year’s, such a clamor arose within the walls of St. Malo that the obnoxious grant was promptly revoked.

But soon a power was in the field against which all St. Malo might clamor in vain. A Catholic nobleman of Brittany, the Marquis de la Roche, bargained with the King to colonize New France. On his part, he was to receive a monopoly of the trade, and a profusion of worthless titles and empty privileges. He was declared Lieutenant-General of Canada, Hochelaga, Newfoundland, Labrador, and the countries adjacent, with sovereign power within his vast and ill-defined domain. He could levy troops, declare war and peace, make laws, punish or pardon at will, build cities, forts, and castles, and grant out lands in fiefs, seigniories, counties, viscounties, and baronies. Thus was effete and cumbrous feudalism to make a lodgment in the New World. It was a scheme of high-sounding promise, but in performance less than contemptible. La Roche ransacked the prisons, and, gathering thence a gang of thieves and desperadoes, embarked them in a small vessel, and set sail to plant Christianity and civilization in the West. Suns rose and set, and the wretched bark, deep freighted with brutality and vice, held on her course. She was so small that the convicts, leaning over her side, could wash their hands in the water. At length, on the gray horizon they descried a long, gray line of ridgy sand. It was Sable Island, off the coast of Nova Scotia. A wreck lay stranded on the beach, and the surf broke ominously over the long, submerged arms of sand, stretched far out into the sea on the right hand and on the left.

Here La Roche landed the convicts, forty in number, while, with his more trusty followers, he sailed to explore the neighboring coasts, and choose a site for the capital of his new dominion, to which, in due time, he proposed to remove the prisoners. But suddenly a tempest from the west assailed him. The frail vessel was forced to run before the gale, which, howling on her track, drove her off the coast, and chased her back towards France.

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

Meanwhile the convicts watched in suspense for the returning sail. Days passed, weeks passed, and still they strained their eyes in vain across the waste of ocean. La Roche had left them to their fate. Rueful and desperate, they wandered among the sand-hills, through the stunted whortleberry bushes, the rank sand-grass, and the tangled cranberry vines which filled the hollows. Not a tree was to be seen; but they built huts of the fragments of the wreck. For food they caught fish in the surrounding sea, and hunted the cattle which ran wild about the island, sprung, perhaps, from those left here eighty years before by the Baron de Lery. They killed seals, trapped black foxes, and clothed themselves in their skins. Their native instincts clung to them in their exile. As if not content with inevitable miseries, they quarreled and murdered one another. Season after season dragged on. Five years elapsed, and, of the forty, only twelve were left alive. Sand, sea, and sky, — there was little else around them; though, to break the dead monotony, the walrus would sometimes rear his half-human face and glistening sides on the reefs and sand-bars. At length, on the far verge of the watery desert, they descried a sail. She stood on towards the island; a boat’s crew landed on the beach, and the exiles were once more among their countrymen.

When La Roche returned to France, the fate of his followers sat heavy on his mind. But the day of his prosperity was gone. A host of enemies rose against him and his privileges, and it is said that the Due de Mercaeur seized him and threw him into prison. In time, however, he gained a hearing of the King; and the Norman pilot, Chefdhotel, was dispatched to bring the outcasts home.

He reached Sable Island in September, 1603, and brought back to France eleven survivors, whose names are still preserved. When they arrived, Henry the Fourth summoned them into his presence. They stood before him, says an old writer, like river-gods of yore; for from head to foot they were clothed in shaggy skins, and beards of prodigious length hung from their swarthy faces. They had accumulated, on their island, a quantity of valuable furs. Of these Chefdhotel had robbed them; but the pilot was forced to disgorge his prey, and, with the aid of a bounty from the King, they were enabled to embark on their own account in the Canadian trade. To their leader, fortune was less kind. Broken by disaster and imprisonment, La Roche died miserably.

In the mean time, on the ruin of his enterprise, a new one had been begun. Pontgrave, a merchant of St. Malo, leagued himself with Chauvin, a captain of the navy, who had influence at court. A patent was granted to them, with the condition that they should colonize the country. But their only thought was to enrich themselves.

At Tadoussac, at the mouth of the Saguenay, under the shadow of savage and inaccessible rocks, feathered with pines, firs, and birch-trees, they built a cluster of wooden huts and store-houses. Here they left sixteen men to gather the expected harvest of furs. Before the winter was over, several of them were dead, and the rest scattered through the woods, living on the charity of the Indians.

– Pioneers of France in the New World Part II, Chapter 2 by Francis Parkman

This is why the first Canadian colonies failed.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Introduction.

If, at times, it may seem that range has been allowed to fancy, it is so in appearance only; since the minutest details of narrative or description rest on authentic documents or on personal observation.

Faithfulness to the truth of history involves far more than a research, however patient and scrupulous, into special facts. Such facts may be detailed with the most minute exactness, and yet the narrative, taken as a whole, may be unmeaning or untrue. The narrator must seek to imbue himself with the life and spirit of the time. He must study events in their bearings near and remote; in the character, habits, and manners of those who took part in them, he must himself be, as it were, a sharer or a spectator of the action he describes.

With respect to that special research which, if inadequate, is still in the most emphatic sense indispensable, it has been the writer’s aim to exhaust the existing material of every subject treated. While it would be folly to claim success in such an attempt, he has reason to hope that, so far at least as relates to the present volume, nothing of much importance has escaped him. With respect to the general preparation just alluded to, he has long been too fond of his theme to neglect any means within his reach of making his conception of it distinct and true.

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

Here is a Kindle version: Complete Works for just $2.

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Biography of Samuel de Champlain.

- Article on New France in North America.

- From the Canada History Project.

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.