The freedom of love and marriage was restrained among the Romans by natural and civil impediments.

Justinian Code Published, featuring a series of excerpts selected from The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by Edward Gibbon published in 1788.

Previously in Justinian Code Published. Now we continue.

Time: 534

Place: Constantinople

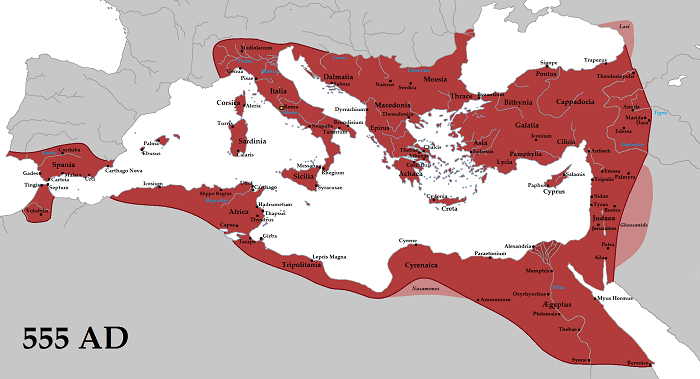

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

The Christian princes were the first who specified the just causes of a private divorce; their institutions, from Constantine to Justinian, appear to fluctuate between the custom of the empire and the wishes of the Church, and the author of the Novels too frequently reforms the jurisprudence of the Code and Pandects. In the most rigorous laws, a wife was condemned to support a gamester, a drunkard, or a libertine, unless he were guilty of homicide, poison, or sacrilege, in which cases the marriage, as it should seem, might have been dissolved by the hand of the executioner.

But the sacred right of the husband was invariably maintained, to deliver his name and family from the disgrace of adultery: the list of mortal sins, either male or female, was curtailed and enlarged by successive regulations, and the obstacles of incurable impotence, long absence, and monastic profession were allowed to rescind the matrimonial obligation. Whoever transgressed the permission of the law was subject to various and heavy penalties. The woman was stripped of her wealth and ornaments, without excepting the bodkin of her hair: if the man introduced a new bride into his bed, her fortune might be lawfully seized by the vengeance of his exiled wife. Forfeiture was sometimes commuted to a fine; the fine was sometimes aggravated by transportation to an island or imprisonment in a monastery; the injured party was released from the bonds of marriage; but the offender during life or a term of years was disabled from the repetition of nuptials. The successor of Justinian yielded to the prayers of his unhappy subjects, and restored the liberty of divorce by mutual consent: the civilians were unanimous, the theologians were divided, and the ambiguous word, which contains the precept of Christ, is flexible to any interpretation that the wisdom of a legislator can demand.

The freedom of love and marriage was restrained among the Romans by natural and civil impediments. An instinct, almost innate and universal, appears to prohibit the incestuous commerce of parents and children in the infinite series of ascending and descending generations. Concerning the oblique and collateral branches nature is indifferent, reason mute, and custom various and arbitrary. In Egypt the marriage of brothers and sisters was admitted without scruple or exception: a Spartan might espouse the daughter of his father, an Athenian that of his mother; and the nuptials of an uncle with his niece were applauded at Athens as a happy union of the dearest relations.

The profane law-givers of Rome were never tempted by interest or superstition to multiply the forbidden degrees: but they inflexibly condemned the marriage of sisters and brothers, hesitated whether first cousins should be touched by the same interdict; revered the parental character of aunts and uncles, and treated affinity and adoption as a just imitation of the ties of blood. According to the proud maxims of the republic, a legal marriage could only be contracted by free citizens; an honorable, at least an ingenuous birth, was required for the spouse of a senator: but the blood of kings could never mingle in legitimate nuptials with the blood of a Roman; and the name of Stranger degraded Cleopatra and Berenice to live the concubines of Mark Antony and Titus. This appellation, indeed, so injurious to the majesty, cannot without indulgence be applied to the manners of these oriental queens. A concubine, in the strict sense of the civilian, was a woman of servile or plebeian extraction, the sole and faithful companion of a Roman citizen, who continued in a state of celibacy. Her modest station, below the honors of a wife, above the infamy of a prostitute, was acknowledged and approved by the laws: from the age of Augustus to the tenth century, the use of this secondary marriage prevailed both in the West and East; and the humble virtues of a concubine were often preferred to the pomp and insolence of a noble matron. In this connection the two Antonines, the best of princes and of men, enjoyed the comforts of domestic love; the example was imitated by many citizens impatient of celibacy, but regardful of their families. If at any time they desired to legitimate their natural children, the conversion was instantly performed by the celebration of their nuptials with a partner whose fruitfulness and fidelity they had already tried. By this epithet of natural, the offspring of the concubine were distinguished from the spurious brood of adultery, prostitution, and incest, to whom Justinian reluctantly grants the necessary aliments of life; and these natural children alone were capable of succeeding to a sixth part of the inheritance of their reputed father. According to the rigor of law, bastards were entitled to the name and condition of their mother, from whom they might derive the character of a slave, a stranger, or a citizen. The outcasts of every family were adopted without reproach as the children of the State.

The relation of guardian and ward, or in Roman words of tutor and pupil, which covers so many titles of the Institutes and Pandects, is of a very simple and uniform nature. The person and property of an orphan must always be trusted to the custody of some discreet friend. If the deceased father had not signified his choice, the agnats, or paternal kindred of the nearest degree, were compelled to act as the natural guardians: the Athenians were apprehensive of exposing the infant to the power of those most interested in his death; but an axiom of Roman jurisprudence has pronounced that the charge of tutelage should constantly attend the emolument of succession. If the choice of the father and the line of consanguinity afforded no efficient guardian, the failure was supplied by the nomination of the praetor of the city or the president of the province. But the person whom they named to this public office might be legally excused by insanity or blindness, by ignorance or inability, by previous enmity or adverse interest, by the number of children or guardianships with which he was already burdened and by the immunities which were granted to the useful labors of magistrates, lawyers, physicians, and professors.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.