The Rio San Gabriel, at the spot where this action was fought, is about one hundred yards wide, the current about knee-deep, flowing over a quicksand bottom.

California Acquired by the United States, featuring a series of excerpts selected from Battles of the United States by Sea and Land by Henry B. Dawson published in 1858.

Previously in California Acquired by the United States. Now we continue.

Time: 1846

Place: California

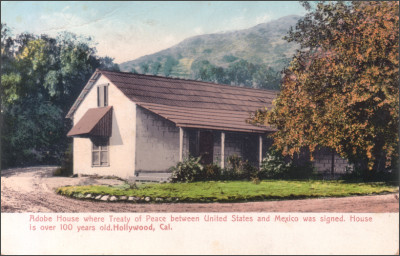

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

At this time commenced that memorable conflict between the two commanders — General Kearney and Commodore Stockton — respecting the chief command, which subsequently created so much trouble in the American ranks and throughout the country. Commodore Stockton appears, however, to have retained the authority; and, having organized a force sufficiently strong to warrant the undertaking, and General Kearney having accepted an invitation to accompany the expedition, on December 29th he marched from San Diego, with two officers and fifty-five privates (dragoons, two officers and forty-five seamen acting as artillerymen; eighteen officers and three hundred seventy-nine seamen and marines acting as infantry; six officers, and fifty-four privates), volunteers, and six pieces of artillery, against the main body of the insurgents, near Los Angeles. The command appears to have been given, at his own request, to General Kearney; and as the wagon train was heavily laden, the progress of the column was very slow–the expedition reaching the Rio San Gabriel on January 8, 1847–although the enemy had offered no opposition to its progress even in passes where a small force could have effectively kept it back. At this place, however, he had made a stand to dispute the passage of the river; and here the second action was fought between the Americans and the Californians.

The Rio San Gabriel, at the spot where this action was fought, is about one hundred yards wide, the current about knee-deep, flowing over a quicksand bottom. The left bank, by which the Americans approached, is level; that on the right is also level for a short distance back, but beyond this narrow plain a bank fifty feet in height commands the ford and the intervening flat, while both banks are fringed with a thick undergrowth. On this bank, directly in front of the ford, four pieces of artillery were posted, supported on either flank by strong bodies of cavalry, while on the slope of the hill and the flat in front were posted the sharpshooters.

Against this position the American column moved; the second division in front, with the first and third divisions on the right and left flanks; the cattle and the wagon train moved next; the volunteer riflemen and the fourth division brought up the rear. As the head of the column approached the bank of the river the enemy’s sharpshooters opened a scattering fire; and the second division was ordered to deploy as skirmishers, cross the river, and drive the former from the thicket; while the first and third divisions covered the flanks of the train, and, with it, followed in the rear. When this line of skirmishers had reached the middle of the stream and was pressing forward toward the opposite bank, the enemy brought his artillery to bear, “and made the water fly with grape and round shot”; and the American fieldpieces were immediately dragged across the river and placed in counter-battery on the right bank in opposition to those of the enemy. The fire of the Americans appears to have caused considerable confusion in the ranks of the insurgents; and under its cover the wagon train and cattle, with their guard, passed the river, during which time the enemy attacked its rear and was repelled.

Having safely crossed the river the American column appears to have deployed under cover of the high ground–the Californian grape and round shot rattling over the heads of the men — and the enemy immediately charged on both its flanks simultaneously, dashing down the slope with great spirit. With great coolness the second division was thrown into squares, and after a round or two drove off the enemy from the left flank; the first division received a similar order, but as the assailants on the right hesitated and did not come down as far as their associates on the opposite flank, the order was countermanded, and the division was ordered to charge up the hill, where the enemy’s main body was supposed to be posted. With great coolness this movement was executed and the heights were gained, but there was no enemy in sight. He had abandoned his position, and although he pitched his camp on the hills in view of the Americans, when morning came he had moved still farther back.

The strength of the Americans in this action (the action of the Rio San Gabriel) had been shown already; that of the Californians was about six hundred, with four pieces of artillery. The loss of the former was one man killed and nine men wounded; that of the enemy is not known.

On the following morning (January 9, 1847) the American column resumed its march over the Mesa — a wide plain which extends from the Rio San Gabriel to the Rio San Fernando — surrounded by reconnoitering parties from the enemy; and when about four miles from Los Angeles the enemy was discovered on the right of the line of march, awaiting its approach. When the column had come abreast of the enemy the latter opened fire from his artillery on its right flank, and soon afterward deployed his force, making a horseshoe in front of the American column, and opening with two pieces of artillery on its front while two nine-pounders continued their fire on the right.

After stopping about fifteen minutes to silence the enemy’s nine-pounders the column again moved forward; when, by a movement similar to that employed on the Rio San Gabriel the day before, two charges were made simultaneously on its left flank and on its right and rear. Contrary to the positive instructions of the officers, in the former of these charges the enemy was met with a fire at long distance; yet, although he had not come within a hundred yards of the column, several of his men were knocked out of their saddles, and a round of grape, which was immediately sent after him, completely scattered his right wing. The charge on the right and the rear of the column fared little better; and the entire force of the insurgents was withdrawn.

The strength of both parties was probably as on the preceding day at the Rio San Gabriel; the loss of the Californians is not known; that of the Americans was Captain Gillespie, Lieutenant Rowan, and three men wounded. The troops encamped near the field of battle; and on the following morning (January 10, 1847), the enemy surrendered, when the city of Los Angeles was occupied by the Americans without further opposition.

“This was the last exertion made by the sons of California for the liberty and independence of their country,” say the Mexican historians, “and its defense will always do them honor; since, without supplies, without means or instructions, they rushed into an unequal contest, in which they more than once taught the invaders what a people can do who fight in defense of their rights. The city of Los Angeles was occupied by the American forces on January 10th, and the loss of that rich, vast, and precious part of the Mexican territory was consummated.”

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages California Acquired by the United States by Henry B. Dawson from his book Battles of the United States by Sea and Land published in 1858. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.