This series has nine easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Where Should the Pilgrims Go?

Introduction

Unfashionable today as they were then (how history travels in circles!) the Puritans came to the New World to create a society that would honor God as they saw it. Their zeal and dedication carried them through terrible hardships. Setting high goals, it tempts the hypocrisy haters to focus on the gaps between actual achievements and goals. But even if there is a little bit of Don Quixote in their aspirations, was it still better to try and fail than to not try at all?

This selection is from «The History of Massachusetts by John Stetson Barry published in 1855.

John S. Barry wrote the definitive history of Massachusetts.

Time: 1620

Place: Plymouth, Massachussets

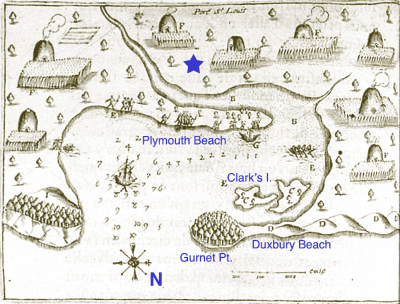

Blue marks added. Star is site of settlement.

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

For several years the exiled Pilgrims abode at Leyden in comparative peace. So mutual was the esteem of both pastor and people that it might be said of them, “as of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius and the people of Rome: it was hard to judge whether he delighted more in having such a people, or they in having such a pastor.” With their spiritual, their temporal interests were objects of his care, so that he was “every way as a common father to them.” And when removed from them by death, as he was in a few years, they sustained “such a loss as they saw could not be easily repaired, for it was as hard for them to find such another leader and feeder as the Taborites to find another Ziska.”

Eight years’ residence, however, in a land of strangers, subjected to its trials and burdened with its sorrows, satisfied this little band that Holland could not be for them a permanent home. The “hardness of the place” discouraged their friends from joining them. Premature age was creeping upon the vigorous. Severe toil enfeebled their children. The corruption of the Dutch youth was pernicious in its influence. They were Englishmen, attached to the land of their nativity. The Sabbath, to them a sacred institution, was openly neglected. A suitable education was difficult to be obtained for their children. The truce with Spain was drawing to a close, and the renewal of hostilities was seriously apprehended. But the motive above all others which prompted their removal was a “great hope and inward zeal of laying some good foundation for the propagating and advancing of the Gospel of the Kingdom of Christ in these remote parts of the world; yea, though they should be but as stepping-stones to others for performing of so great a work.”

For these reasons–and were they frivolous?–a removal was resolved upon. They could not in peace return to England. It was dangerous to remain in the land of their exile. Whither, then, should they go? Where should an asylum for their children be reared? This question, so vital, was first discussed privately, by the gravest and wisest of the Church; then publicly, by all. The “casualties of the seas,” the “length of the voyage,” the “miseries of the land,” the “cruelty of the savages,” the “expense of the outfit,” the “ill-success of other colonies,” and “their own sad experience” in their removal to Holland were urged as obstacles which must doubtless be encountered. But, as a dissuasive from discouragement, it was remarked that “all great and honorable actions are accompanied with great difficulties, and must both be enterprised and overcome with answerable courages. It was granted the dangers very great, but not invincible; for although there were many of them likely, yet they were not certain. Some of the things they feared might never befall them; others, by providence, care, and the use of good means might in a great measure be prevented; and all of them, through the help of God, by fortitude or patience might either be borne or overcome.”

Whither should they turn their steps? Some, and “none of the meanest,” were “earnest for Guiana.” Others, of equal worth, were in favor of Virginia, “where the English had already made entrance and beginning.” But a majority were for “living in a distinct body by themselves, though under the general government of Virginia.” For Guiana, it was said, “the country was rich, fruitful, and blessed with a perpetual spring and a flourishing greenness”; and the Spaniards “had not planted there nor anywhere near the same.” Guiana was the El Dorado of the age. Sir Walter Raleigh, its discoverer, had described its tropical voluptuousness in the most captivating terms; and Chapman, the poet, dazzled by its charms, exclaims:

Guiana, whose rich feet are mines of gold,

Whose forehead knocks against the roof of stars,

Stands on her tiptoe at fair England looking,

Kissing her hands, bowing her mighty breast,

And every sign of all submission making,

To be the sister and the daughter both

Of our most sacred maid.”

Is it surprising that the thoughts of the exiles were enraptured in contemplating this beautiful land? Was it criminal to seek a pleasant abode? But as an offset to its advantages, its “grievous diseases” and “noisome impediments” were vividly portrayed; and it was urged that, should they settle there and prosper, the “jealous Spaniard” might displace and expel them, as he had already the French from their settlements in Florida; and this the sooner, as there would be none to protect them, and their own strength was inadequate to cope with so powerful an adversary.

Against settling in Virginia it was urged that, “if they lived among the English there planted, or under their government, they would be in as great danger to be persecuted for the cause of religion as if they lived in England, and it might be worse, and, if they lived too far off, they should have neither succor nor defence from them.” Upon the whole, therefore, it was decided to “live in a distinct body by themselves, under the general government of Virginia, and by their agents to sue his majesty to grant them free liberty and freedom of religion.”

| Master List | Next—> |

315451 74424Thank you a good deal for giving everybody an extraordinarily unique possiblity to check ideas from here. 498474