All that could be obtained from the King after the most diligent “sounding” was a verbal promise that “he would connive at them and not molest them, provided they conducted themselves peaceably; but to allow or tolerate them under his seal” he would not consent.”

The Pilgrims Settle Plymouth, Massachussets, featuring a series of excerpts selected from by John S. Barry.

Previously in The Pilgrims Settle Plymouth, Massachussets. Now we continue.

Time: 1620

Place: Plymouth, Massachussets

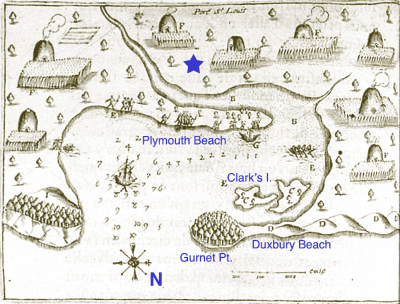

Blue marks added. Star is site of settlement.

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Accordingly John Carver, one of the deacons of the Church, and Robert Cushman, a private member, were sent to England to treat with the Virginia Company for a grant of land, and to solicit of the King liberty of conscience. The friends from whom aid was expected, and to some of whom letters were written, were Sir Edwin Sandys, the distinguished author of the Europe Speculum; Sir Robert Maunton, afterward secretary of state; and Sir John Wolstenholme, an eminent merchant and a farmer of the customs. Sir Ferdinando Georges seems also to have been interested in their behalf, as he speaks of means used by himself, before his rupture with the Virginia Company, to “draw into their enterprises some of those families that had retired into Holland, for scruple of conscience, giving them such freedom and liberty as might stand with their likings.”

The messengers–“God going along with them”–bore a missive signed by the principal members of the Church, commending them to favor, and conducted their mission with discretion and propriety; but as their instructions were not plenary, they soon returned, bearing a letter from Sir Edwin Sandys, approving their diligence and proffering aid. The next month a second embassy was despatched, with an answer to Sir Edwin’s letter, in which, for his encouragement, the exiles say:

We believe and trust the Lord is with us, and will graciously prosper our endeavors accordingly to the simplicity of our hearts therein. We are well weaned from the delicate milk of our mother-country and inured to the difficulties of a strange and hard land. The people are, for the body of them, industrious and frugal. We are knit together in a strict and sacred bond and covenant of the Lord, of the violation whereof we make great conscience, and by virtue whereof we hold ourselves strictly tied to all care of others’ goods. It is not with us, as with others, whom small things can discourage, or small discontentments cause to wish themselves at home again.”

For the information of the council of the company, the “requests” of the Church were sent, signed by nearly the whole congregation, and, in a letter to Sir John Wolstenholme, explanation was given of their “judgments” upon three points named by his majesty’s privy council, in which they affirmed that they differed nothing in doctrine and but little in discipline from the French reformed churches, and expressed their willingness to take the oath of supremacy if required, “if that convenient satisfaction be not given by our taking the oath of allegiance.”

The new agents, upon their arrival in England, found the Virginia Company anxious for their emigration to America, and “willing to give them a patent with as ample privileges as they had or could grant to any”; and some of the chief members of the company “doubted not to obtain their suit of the King for liberty in religion.” But the last “proved a harder work than they took it for.” Neither James nor his bishops would grant such a request. The “advancement of his dominions” and “the enlargement of the Gospel” his majesty acknowledged to be “an honorable motive”; and “fishing”–the secular business they expected to follow–“was an honest trade, the apostle’s own calling”; but for any further liberties he referred them to the prelates of Canterbury and London. All that could be obtained from the King after the most diligent “sounding” was a verbal promise that “he would connive at them and not molest them, provided they conducted themselves peaceably; but to allow or tolerate them under his seal” he would not consent.

With this answer the messengers returned, and their report was discouraging to the hopes of the exiles. Should they trust their monarch’s word, when bitter experience had taught them the ease with which it could be broken? And yet, reasoned some, “his word may be as good as his bond; for if he purposes to injure us, though we have a seal as broad as the house-floor, means will be found to recall or reverse it.” In this as in other matters, therefore, they relied upon Providence, trusting that distance would prove as effectual a safeguard as the word of a prince which had been so often forfeited.

Accordingly other agents were sent to procure a patent, and to negotiate with such merchants as had expressed a willingness to aid them with funds. On reaching England these agents found a division existing in the Virginia Company, growing out of difficulties between Sir Thomas Smith and Sir Edwin Sandys; and disagreeable intelligence had been received from Virginia of disturbances in the colony which had there been established. For these reasons little could be immediately effected. At length, after tedious delays, and “messengers passing to and fro,” a patent was obtained, which, by the advice of friends, was taken in the name of John Wincob, a gentleman in the family of the Countess of Lincoln; and with this document, and the proposals of Mr. Thomas Weston, one of the agents returned, and submitted the same to the Church for inspection. The nature of these proposals has never transpired, nor is the original patent–the first which the Pilgrims received–known to be in existence. Future inquirers may discover this instrument, as recently other documents have been rescued from oblivion. We should be glad to be acquainted with its terms, were it only to know definitely the region it embraced. But if ever discovered, we will hazard the conjecture that it will be found to cover territory now included in New York.

Upon the reception of the patent and the accompanying proposals, as every enterprise of the Pilgrims began from God–a day of fasting and prayer was appointed to seek divine guidance; and Mr. Robinson, whose services were ever appropriate, discoursed to his flock from the words in Samuel; “And David’s men said unto him, See, we be afraid here in Judah: how much more if we come to Keilah, against the host of the Philistines?”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.