On Monday, December 11th, O. S., a landing was effected upon Forefather’s Rock. The site of this stone was preserved by tradition, and a venerable contemporary of several of the Pilgrims, whose head was silvered with the frost of ninety-five winters, settled the question of its identity in 1741.

The Pilgrims Settle Plymouth, Massachusetts, featuring a series of excerpts selected from by John S. Barry.

Previously in The Pilgrims Settle Plymouth, Massachussets. Now we continue.

Time: 1620

Place: Plymouth, Massachussets

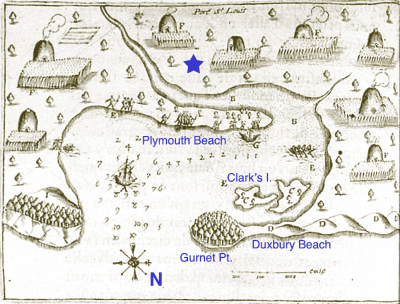

Blue marks added. Star is site of settlement.

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Ten days after, another expedition was fitted out, in which twenty-five of the colonists and nine or ten of the sailors, with Jones at their head, were engaged; and visiting the mouth of the Pamet, called by them “Cold Harbor,” and obtaining fresh supplies from the aboriginal granaries, after a brief absence, in which a few unimportant discoveries were made, the party returned. Here a discussion ensued. Should they settle at Cold Harbor or seek a more eligible site? In favor of the former it was urged that the harbor was suitable for boats, if not for ships; the corn land was good; it was convenient to their fishing-grounds; the location was healthy; winter was approaching; travelling was dangerous; their provisions were wasting; and the captain of the Mayflower was anxious to return. On the other hand, it was replied that a better place might be found; it would be a hinderance to move a second time; good spring-water was wanting; and lastly, at Agawam, now Ipswich, twenty leagues to the north, was an excellent harbor, better ground, and better fishing. Robert Coppin, their pilot, likewise informed them of “a great and navigable river and good harbour in the other headland of the bay, almost right over against Cape Cod,” which he had formerly visited, and which was called “Thievish Harbor.”

A third expedition, therefore, was agreed upon; and though the weather was unfavorable, and some difficulty was experienced in clearing Billingsgate Point, they reached the weather shore, and there “had better sailing.” Yet bitter was the cold, and the spray, as it froze on them, gave them the appearance of being encased in glittering mail. At night their rendezvous was near Great Meadow Creek; and early in the morning, after an encounter with the Indians, in which no one was wounded, their journey was resumed, their destination being the harbor which Coppin had described to them, and which he assured them could be reached in a few hours’ sailing. Through rain and snow they steered their course; but by the middle of the afternoon a fearful storm raged; the hinges of their rudder were broken; the mast was split, the sail was rent, and the inmates of the shallop were in imminent peril; yet, by God’s mercy, they survived the first shock, and, favored by a flood tide, steered into the harbor. A glance satisfied the pilot that it was not the place he sought; and in an agony of despair he exclaimed: “Lord be merciful to us! My eyes never saw this place before!” In his frenzy he would have run the boat ashore among the breakers; but an intrepid seaman resolutely shouted, “About with her, or we are lost!” And instantly obeying, with hard rowing, dark as it was, with the wind howling fiercely, and the rain dashing furiously, they shot under the lee of an island and moored until morning.

The next day the island was explored — now known as Clarke’s Island — and the clothing of the adventurers was carefully dried; but, excusable as it might have been under the circumstances in which they were placed to have immediately resumed their researches, the Sabbath was devoutly and sacredly observed.

The Rock

On Monday, December 11th, O. S., a landing was effected upon Forefather’s Rock. The site of this stone was preserved by tradition, and a venerable contemporary of several of the Pilgrims, whose head was silvered with the frost of ninety-five winters, settled the question of its identity in 1741. Borne in his arm-chair by a grateful populace, Elder Faunce took his last look at the spot so endeared to his memory, and, bedewing it with tears, he bade it farewell. In 1774 this precious boulder, as if seized with the spirit of that bustling age, was raised from its bed to be consecrated to Liberty, and in the act of its elevation it split in twain–an occurrence regarded by many as ominous of the separation of the colonies from England, and the lower part being left in the spot where it still lies, the upper part, weighing several tons, was conveyed, amid the heartiest rejoicings, to Liberty-pole Square, and adorned with a flag bearing the imperishable motto, “Liberty or Death.” On July 4, 1834, the natal day of the freedom of the colonies, this part of the rock was removed to the ground in front of Pilgrim Hall, and there it rests, encircled with a railing, ornamented with heraldic wreaths, bearing the names of the forty-one signers of the compact in the Mayflower. Fragments of this rock are relics in the cabinets of hundreds of our citizens, and are sought with avidity even by strangers as memorials of a pilgrimage to the birthplace of New England.

On the day of landing the harbor was sounded and the land explored; and, the place inviting settlement, the adventurers returned with tidings of their success; the Mayflower weighed anchor to proceed to the spot; and ere another Sabbath dawned she was safely moored in the desired haven. Monday and Tuesday were spent in exploring tours; and on Wednesday, the 20th, the settlement at Plymouth was commenced–twenty persons remaining ashore for the night. On the following Saturday the first timber was felled; on Monday their storehouse was commenced; on Thursday preparations were made for the erection of a fort; and allotments of land were made to the families; and on the following Sunday religious worship was performed for the first time in their storehouse.

For a month the colonists were busily employed. The distance of the vessel–which lay more than a mile from the shore–was a great hinderance to their work; frequent storms interrupted their operations; and by accident their storehouse was destroyed by fire, and their hospital narrowly escaped destruction. The houses were arranged in two rows, on Leyden street, each man building his own. The storehouse was twenty feet square; the size of the private dwellings we have no means of determining. All were constructed of logs, with the interstices filled with sticks and clay; the roofs were covered with thatch; the chimneys were of fragments of wood, plastered with clay; and oiled paper served as a substitute for glass for the inlet of light.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Hi there, I enjoy reading through your article. I wanted to write a little comment to support you.