The particulars of this voyage, more memorable by far than the famed expedition of the Argonauts, and paralleled, if at all, only by the voyage of Columbus, are few and scanty.

The Pilgrims Settle Plymouth, Massachussets, featuring a series of excerpts selected from by John S. Barry.

Previously in The Pilgrims Settle Plymouth, Massachussets. Now we continue.

Time: 1620

Place: Plymouth, Massachussets

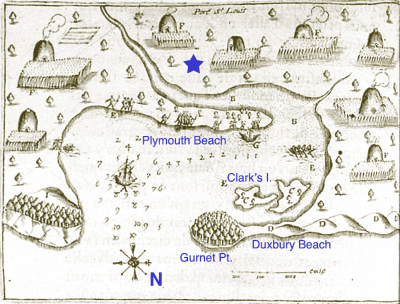

Blue marks added. Star is site of settlement.

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

At the conclusion of this discourse those who were to leave were feasted at their pastor’s house, where, after “tears,” warm and gushing, from the fulness of their hearts, the song of praise and thanksgiving was raised; and “truly,” says an auditor, “it was the sweetest melody that ever mine ears heard.” But the parting hour has come! The Speedwell lies at Delfthaven, twenty-two miles south of Leyden, and thither the emigrants are accompanied by their friends, and by others from Amsterdam who are present to pray for the success of their voyage.

So they left that goodly and pleasant city, which had been their resting-place near twelve years. But they knew they were Pilgrims, and looked not much on those things, and quieted their spirits.”

The last night was spent “with little sleep by the most, but with friendly entertainment and Christian discourse, and other real expressions of true Christian love.” On the morrow they sailed; “and truly doleful was the sight of that sad and mournful parting; to see what sighs and sobs and prayers did sound among them; what tears did gush from every eye, and pithy speeches pierced each other’s hearts; that sundry of the Dutch strangers, that stood on the quay as spectators, could not refrain from tears. Yet comfortable and sweet it was to see such lively and true expressions of dear and unfeigned love. But the tide, which stays for no man, calling them away that were thus loth to depart, their reverend pastor, falling down on his knees, and they all with him, with watery cheeks, commended them with most fervent prayers to the Lord and his blessing; and then, with mutual embraces and many tears, they took their leave one of another, which proved to be the last leave to many of them.”

At starting they gave their friends “a volley of small shot and three pieces of ordnance”; and so, “lifting up their hands to each other, and their hearts for each other to the Lord God,” they set sail, and found his presence with them, “in the midst of the manifold straits he carried them through.” Favored by a prosperous gale they soon reached Southampton, where lay the Mayflower in readiness with the rest of their company; and after a joyful welcome and mutual congratulations, they “fell to parley about their proceedings.”

In about a fortnight the Speedwell, commanded by Captain Reynolds, and the Mayflower, commanded by Captain Jones–both having a hundred twenty passengers on board–were ready to set out to cross the Atlantic. Overseers of the provisions and passengers were selected; Mr. Weston and others were present to witness their departure; and the farewell was said to the friends they were to leave. But “not every cloudless morning is followed by a pleasant day.” Scarcely had the two barks left the harbor ere Captain Reynolds complained of the leakiness of the Speedwell, and both put in at Dartmouth for repairs. At the end of eight precious days they started again, but had sailed “only a hundred leagues beyond the land’s end” when the former complaints were renewed, and the vessels put in at Plymouth, where, “by the consent of the whole company,” the Speedwell was dismissed; and as the Mayflower could accommodate but one hundred passengers, twenty of those who had embarked in the smaller vessel — including Mr. Cushman and his family–were compelled to return; and matters being ordered with reference to this arrangement, “another sad parting took place.”

Finally, after the lapse of two more precious weeks, the Mayflower, “freighted with the destinies of a continent,” and having on board one hundred passengers, resolute men, women, and children, “loosed from Plymouth”–“her inmates having been kindly entertained and courteously used by divers friends there dwelling” — and, with the wind “east-northeast, a fine small gale,” was soon far at sea.

The particulars of this voyage, more memorable by far than the famed expedition of the Argonauts, and paralleled, if at all, only by the voyage of Columbus, are few and scanty. Though fair winds wafted the bark onward for a season, contrary winds and fierce storms were soon encountered, by which she was “shrewdly shaken” and her “upper works made very leaky.” One of the main beams of the midship was also “bowed and cracked,” but a passenger having brought with him “a large iron screw,” the beam was replaced and carefully fastened, and the vessel continued on. During this storm John Howland, “a stout young man,” was by a “heel of the ship thrown into the sea, but catching by the halliards, which hung overboard, he kept his hold, and was saved.” “A profane and proud young seaman,” also, “stout and able of body, who had despised the poor people in their sickness, telling them he hoped to help cast off half of them overboard before they came to their journey’s end, and to make merry with what they had, was smitten with a grievous disease, of which he died in a desperate manner, and was himself the first thrown overboard, to the astonishment of all his fellows.” One other death occurred–that of William Button, a servant of Dr. Fuller; and there was one birth, in the family of Stephen Hopkins, of a son, christened “Oceanus,” who died shortly after the landing. The ship being leaky, and the passengers closely stowed, their clothes were constantly wet. This added much to the discomfort of the voyage, and laid a foundation for a portion of the mortality which prevailed the first winter.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.