The harbor in which the Mayflower now lay is worthy of a passing glance.”

The Pilgrims Settle Plymouth, Massachussets, featuring a series of excerpts selected from by John S. Barry.

Previously in The Pilgrims Settle Plymouth, Massachussets. Now we continue.

Time: 1620

Place: Plymouth, Massachussets

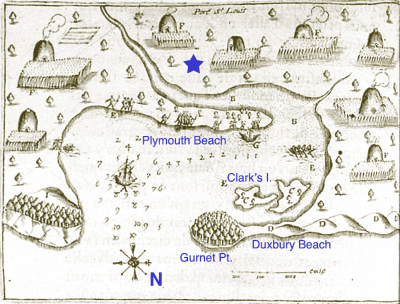

Blue marks added. Star is site of settlement.

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

“Land-ho!” This welcome cry was not heard until two months had elapsed, and the sandy cliffs of Cape Cod were the first points which greeted the eyes of the exiles. Yet the appearance of these cliffs “much comforted them, and caused them to rejoice together, and praise God, that had given them once again to see land.” Their destination, however, was to “the mouth of the Hudson,” and now they were much farther to the north, and within the bounds of the New England Company. They therefore “tacked to stand to the southward,” but “becoming entangled among roaring shoals, and the wind shrieking upon them withal, they resolved to bear up again for the Cape,” and the next day, “by God’s providence, they got into Cape harbor,” where, falling upon their knees, they “blessed the Lord, the God of heaven, who had brought them over the vast and furious ocean, and delivered them from all perils and miseries, therein, again to set their feet on the firm and stable earth, their proper element.”

Morton, in his memorial, asserts that the Mayflower put in at this cape, “partly by reason of a storm by which she was forced in, but more especially by the fraudulency and contrivance of the aforesaid Mr. Jones, the master of the ship; for their intention and his engagement was to Hudson’s river; but some of the Dutch having notice of their intention, and having thoughts about the same time of erecting a plantation there likewise, they fraudulently hired the said Jones, by delays, while they were in England, and now under the pretence of the sholes, etc., to disappoint them in their going thither. Of this plot betwixt the Dutch and Mr. Jones I have had late and certain intelligence.” The explicitness of this assertion has caused charge of treachery — brought by no one but Morton — to be repeated by almost every historian down to the present period; and it is only within a few years that its correctness has been questioned by writers whose judgment is entitled to respect. But notwithstanding the plausibility of the arguments urged to disprove this charge, and even the explicit assertion that it is a “Parthian calumny,” and a “sheer falsehood,” we must frankly own that, in our estimation, the veracity of Morton yet remains unimpeached. Facts prove that the Dutch were contemplating permanent settlement of New Netherland, and the early Pilgrim writers assert that overtures were made to the Leyden Church by the merchants of Holland to join them in that movement, and the petition to the States-General, when presented by those merchants, was finally rejected, and the Mayflower commenced her voyage intending to proceed to the Hudson. Is it improbable that steps may have been taken to frustrate their intention, and that arrangements may even have been made with the captain of that vessel by Dutch agents in England, to alter her course, and land the emigrants farther to the north?

We are aware that one to whose judgment we have usually deferred has said that had the intelligence been early it would have been more certain. But every student of history knows that late intelligence is often more reliable and authentic than early; and if it be asked from what source did Morton obtain his information, we can only suggest that, up to 1664, New Netherlands remained under the dominion of the Dutch, and the history of that colony was in a great measure secret to the English. But several of the prominent settlers of Plymouth had ere this removed to Manhattan — as Isaac Allerton and Thomas Willet — and after the reduction of the country and its subjection to England, from these persons the “late” and “certain” intelligence may have been received, or from access to documents which were before kept private.

The harbor in which the Mayflower now lay is worthy of a passing glance. It is described by Major Grahame as “one of the finest harbors for ships of war on the whole Atlantic coast. The width and freedom from obstructions of every kind, at its entrance, and the extent of sea-room upon the land side, make it accessible to vessels of the largest class in almost all winds. This advantage, its capacity, depth of water, excellent anchorage, and the complete shelter it affords from all winds render it one of the most valuable harbors upon our coast, whether considered in a commercial or a military point of view.”

If to the advantages here enumerated could have been added a fertile soil, and an extensive back country, suitably furnished with timber and fuel, the spot to which this gallant bark was led would have proved as eligible a site for a flourishing colony as could possibly have been desired. But these advantages were wanting; and though our fathers considered it an “extraordinary blessing of God” in directing their course for these parts, which they were at first inclined to consider “one of the most pleasant, most healthful, and most fruitful parts of the world,” longer acquaintance and better information abundantly satisfied them of the insuperable obstacles to agriculture and commerce.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.