But though the acceptance of the laws was accomplished without difficulty, it was not found so easy either for the people to understand and obey, or for the framer to explain them.

Continuing Solon’s Early Greek Legislation,

our selection from History of Greece by George Grote published in 1846. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eighteen easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Solon’s Early Greek Legislation.

Time: 594 BC

Place: Athens

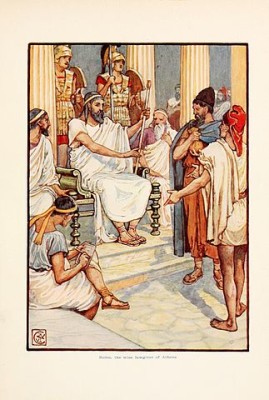

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

It would appear that all the laws of Solon were proclaimed, inscribed, and accepted without either discussion or resistance. He is said to have described them, not as the best laws which he could himself have imagined, but as the best which he could have induced the people to accept. He gave them validity for the space of ten years, during which period both the senate collectively and the archons individually swore to observe them with fidelity; under penalty, in case of non-observance, of a golden statue as large as life to be erected at Delphi. But though the acceptance of the laws was accomplished without difficulty, it was not found so easy either for the people to understand and obey, or for the framer to explain them. Every day persons came to Solon either with praise, or criticism, or suggestions of various improvements, or questions as to the construction of particular enactments; until at last he became tired of this endless process of reply and vindication, which was seldom successful either in removing obscurity or in satisfying complainants. Foreseeing that if he remained he would be compelled to make changes, he obtained leave of absence from his countrymen for ten years, trusting that before the expiration of that period they would have become accustomed to his laws. He quitted his native city in the full certainty that his laws would remain unrepealed until his return; for (says Herodotus) “the Athenians “could not” repeal them, since they were bound by solemn oaths to observe them for ten years.” The unqualified manner in which the historian here speaks of an oath, as if it created a sort of physical necessity and shut out all possibility of a contrary result, deserves notice as illustrating Grecian sentiment.

On departing from Athens, Solon first visited Egypt, where he communicated largely with Psenophis of Heliopolis and Sonchis of Sais, Egyptian priests who had much to tell respecting their ancient history, and from whom he learned matters, real or pretended, far transcending in alleged antiquity the oldest Grecian genealogies–especially the history of the vast submerged island of Atlantis, and the war which the ancestors of the Athenians had successfully carried on against it, nine thousand years before. Solon is said to have commenced an epic poem upon this subject, but he did not live to finish it, and nothing of it now remains. From Egypt he went to Cyprus, where he visited the small town of Æpia, said to have been originally founded by Demophon, son of Theseus, and ruled at this period by the prince Philocyprus–each town in Cyprus having its own petty prince. It was situated near the river Clarius in a position precipitous and secure, but inconvenient and ill-supplied, Solon persuaded Philocyprus to quit the old site and establish a new town down in the fertile plain beneath. He himself stayed and became “æcist” of the new establishment, making all the regulations requisite for its safe and prosperous march, which was indeed so decisively manifested that many new settlers flocked into the new plantation, called by Philocyprus “Soli”, in honor of Solon. To our deep regret, we are not permitted to know what these regulations were; but the general fact is attested by the poems of Solon himself, and the lines in which he bade farewell to Philocyprus on quitting the island are yet before us. On the dispositions of this prince his poem bestowed unqualified commendation.

Besides his visit to Egypt and Cyprus, a story was also current of his having conversed with the Lydian king Croesus at Sardis. The communication said to have taken place between them has been woven by Herodotus into a sort of moral tale which forms one of the most beautiful episodes in his whole history. Though this tale has been told and retold as if it were genuine history, yet as it now stands it is irreconcilable with chronology–although very possibly Solon may at some time or other have visited Sardis, and seen Croesus as hereditary prince.

But even if no chronological objections existed, the moral purpose of the tale is so prominent, and pervades it so systematically from beginning to end, that these internal grounds are of themselves sufficiently strong to impeach its credibility as a matter of fact, unless such doubts happen to be out-weighed–which in this case they are not–by good contemporary testimony. The narrative of Solon and Croesus can be taken for nothing else but an illustrative fiction, borrowed by Herodotus from some philosopher, and clothed in his own peculiar beauty of expression, which on this occasion is more decidedly poetical than is habitual with him. I cannot transcribe, and I hardly dare to abridge it. The vainglorious Croesus, at the summit of his conquests and his riches, endeavors to win from his visitor Solon an opinion that he is the happiest of mankind. The latter, after having twice preferred to him modest and meritorious Grecian citizens, at length reminds him that his vast wealth and power are of a tenure too precarious to serve as an evidence of happiness; that the gods are jealous and meddlesome, and often make the show of happiness a mere prelude to extreme disaster; and that no man’s life can be called happy until the whole of it has been played out, so that it may be seen to be out of the reach of reverses. Croesus treats this opinion as absurd, but “a great judgment from God fell upon him, after Solon was departed–probably (observes Herodotus) because he fancied himself the happiest of all men.”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.