Today’s installment concludes Solon’s Early Greek Legislation,

our selection from History of Greece by George Grote published in 1846 For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of «DaysAlpha» thousand words. Congratulations!

Previously in Solon’s Early Greek Legislation.

Time: 594 BC

Place: Athens

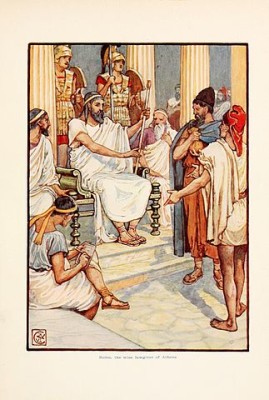

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The unbounded popular favor which had procured the passing of this grant was still further manifested by the absence of all precautions to prevent the limits of the grant from being exceeded. The number of the body-guard was not long confined to fifty, and probably their clubs were soon exchanged for sharper weapons. Pisistratus thus found himself strong enough to throw off the mask and seize the Acropolis. His leading opponents, Megacles and the Alcinæonids, immediately fled the city, and it was left to the venerable age and undaunted patriotism of Solon to stand forward almost alone in a vain attempt to resist the usurpation. He publicly presented himself in the market-place, employing encouragement, remonstrance and reproach, in order to rouse the spirit of the people. To prevent this despotism from coming (he told them) would have been easy; to shake it off now was more difficult, yet at the same time more glorious. But he spoke in vain, for all who were not actually favorable to Pisistratus listened only to their fears, and remained passive; nor did any one join Solon, when, as a last appeal, he put on his armor and planted himself in military posture before the door of his house. “I have done my duty (he exclaimed at length); I have sustained to the best of my power my country and the laws”; and he then renounced all further hope of opposition–though resisting the instances of his friends that he should flee, and returning for answer, when they asked him on what he relied for protection, “On my old age.” Nor did he even think it necessary to repress the inspirations of his Muse. Some verses yet remain, composed seemingly at a moment when the strong hand of the new despot had begun to make itself sorely felt, in which he tells his countrymen —

If ye have endured sorrow from your own baseness of soul, impute not the fault of this to the gods. Ye have yourselves put force and dominion into the hands of these men, and have thus drawn upon yourselves wretched slavery.”

It is gratifying to learn that Pisistratus, whose conduct throughout his despotism was comparatively mild, left Solon untouched. How long this distinguished man survived the practical subversion of his own constitution, we cannot certainly determine; but according to the most probable statement he died during the very next year, at the advanced age of eighty.

We have only to regret that we are deprived of the means of following more in detail his noble and exemplary character. He represents the best tendencies of his age, combined with much that is personally excellent: the improved ethical sensibility; the thirst for enlarged knowledge and observation, not less potent in old age than in youth; the conception of regularized popular institutions, departing sensibly from the type and spirit of the governments around him, and calculated to found a new character in the Athenian people; a genuine and reflecting sympathy with the mass of the poor, anxious not merely to rescue them from the oppressions of the rich, but also to create in them habits of self-relying industry; lastly, during his temporary possession of a power altogether arbitrary, not merely an absence of all selfish ambition, but a rare discretion in seizing the mean between conflicting exigencies. In reading his poems we must always recollect that what now appears commonplace was once new, so that to his comparatively unlettered age the social pictures which he draws were still fresh, and his exhortations calculated to live in the memory. The poems composed on moral subjects generally inculcate a spirit of gentleness toward others and moderation in personal objects. They represent the gods as irresistible, retributive, favoring the good and punishing the bad, though sometimes very tardily. But his compositions on special and present occasions are usually conceived in a more vigorous spirit; denouncing the oppressions of the rich at one time, and the timid submission to Pisistratus at another–and expressing in emphatic language his own proud consciousness of having stood forward as champion of the mass of the people. Of his early poems hardly anything is preserved. The few lines remaining seem to manifest a jovial temperament which we may well conceive to have been overlaid by such political difficulties as he had to encounter–difficulties arising successively out of the Megarian war, the Cylonian sacrilege, the public despondency healed by Epimenides, and the task of arbiter between a rapacious oligarchy and a suffering people. In one of his elegies addressed to Mimnermus, he marked out the sixtieth year as the longest desirable period of life, in preference to the eightieth year, which that poet had expressed a wish to attain. But his own life, as far as we can judge, seems to have reached the longer of the two periods; and not the least honorable part of it (the resistance to Pisistratus) occurs immediately before his death.

There prevailed a story that his ashes were collected and scattered around the island of Salamis, which Plutarch treats as absurd–though he tells us at the same time that it was believed both by Aristotle and by many other considerable men. It is at least as ancient as the poet Cratinus, who alluded to it in one of his comedies, and I do not feel inclined to reject it. The inscription on the statue of Solon at Athens described him as a Salaminian; he had been the great means of acquiring the island for his country, and it seems highly probable that among the new Athenian citizens, who went to settle there, he may have received a lot of land and become enrolled among the Salaminian “demots”. The dispersion of his ashes connecting him with the island as its “oecist”, may be construed, if not as the expression of a public vote, at least as a piece of affectionate vanity on the part of his surviving friends.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages Solon’s Early Greek Legislation by George Grote from his book History of Greece published in 1846. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.