It is much to be regretted that we have no information respecting events in Attica immediately after the Solonian laws and constitution, which were promulgated in B.C. 594, so as to understand better the practical effect of these changes.

Continuing Solon’s Early Greek Legislation,

our selection from History of Greece by George Grote published in 1846. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eighteen easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Solon’s Early Greek Legislation.

Time: 594 BC

Place: Athens

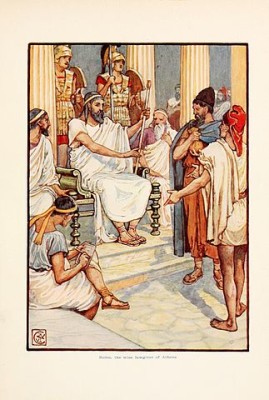

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

First he lost his favorite son Atys, a brave and intelligent youth (his only other son being dumb). For the Mysians of Olympus being ruined by a destructive and formidable wild boar, which they were unable to subdue, applied for aid to Croesus, who sent to the spot a chosen hunting force, and permitted–though with great reluctance, in consequence of an alarming dream–that his favorite son should accompany them. The young prince was unintentionally slain by the Phrygian exile Adrastus, whom Croesus had sheltered and protected, Hardly had the latter recovered from the anguish of this misfortune, when the rapid growth of Cyrus and the Persian power induced him to go to war with them, against the advice of his wisest counsellors. After a struggle of about three years he was completely defeated, his capital Sardis taken by storm, and himself made prisoner. Cyrus ordered a large pile to be prepared, and placed upon it Croesus in fetters, together with fourteen young Lydians, in the intention of burning them alive either as a religious offering, or in fulfilment of a vow, “or perhaps (says Herodotus) to see whether some of the gods would not interfere to rescue a man so preëmiently pious as the king of Lydia.” In this sad extremity, Croesus bethought him of the warning which he had before despised, and thrice pronounced, with a deep groan, the name of Solon. Cyrus desired the interpreters to inquire whom he was invoking, and learnt in reply the anecdote of the Athenian lawgiver, together with the solemn memento which he had offered to Croesus during more prosperous days, attesting the frail tenure of all human greatness. The remark sunk deep into the Persian monarch as a token of what might happen to himself: he repented of his purpose, and directed that the pile, which had already been kindled, should be immediately extinguished. But the orders came too late. In spite of the most zealous efforts of the bystanders, the flame was found unquenchable, and Croesus would still have been burned, had he not implored with prayers and tears the succor of Apollo, to whose Delphian and Theban temples he had given such munificent presents. His prayers were heard, the fair sky was immediately overcast and a profuse rain descended, sufficient to extinguish the flames. The life of Croesus was thus saved, and he became afterward the confidential friend and adviser of his conqueror.

Such is the brief outline of a narrative which Herodotus has given with full development and with impressive effect. It would have served as a show-lecture to the youth of Athens not less admirably than the well-known fable of the Choice of Heracles, which the philosopher Prodicus, a junior contemporary of Herodotus, delivered with so much popularity. It illustrates forcibly the religious and ethical ideas of antiquity; the deep sense of the jealousy of the gods, who would not endure pride in any one except themselves; the impossibility, for any man, of realizing to himself more than a very moderate share of happiness; the danger from a reactionary Nemesis, if at anytime he had overpassed such limit; and the necessity of calculations taking in the whole of life, as a basis for rational comparison of different individuals. And it embodies, as a practical consequence from these feelings, the often-repeated protest of moralists against vehement impulses and unrestrained aspirations. The more valuable this narrative appears, in its illustrative character, the less can we presume to treat it as a history.

It is much to be regretted that we have no information respecting events in Attica immediately after the Solonian laws and constitution, which were promulgated in B.C. 594, so as to understand better the practical effect of these changes. What we next hear respecting Solon in Attica refers to a period immediately preceding the first usurpation of Pisistratus in B.C. 560, and after the return of Solon from his long absence. We are here again introduced to the same oligarchical dissensions as are reported to have prevailed before the Solonian legislation: the Pediis, or opulent proprietors of the plain round Athens, under Lycurgus; the Parali of the south of Attica, under Megacles; and the Diacrii or mountaineers of the eastern cantons, the poorest of the three classes, under Pisistratus, are in a state of violent intestine dispute. The account of Plutarch represents Solon as returning to Athens during the height of this sedition. He was treated with respect by all parties, but his recommendations were no longer obeyed, and he was disqualified by age from acting with effect in public. He employed his best efforts to mitigate party animosities, and applied himself particularly to restrain the ambition of Pisistratus, whose ulterior projects he quickly detected.

The future greatness of Pisistratus is said to have been first portended by a miracle which happened, even before his birth, to his father Hippocrates at the Olympic games. It was realized, partly by his bravery and conduct, which had been displayed in the capture of Nisæa from the Megarians–partly by his popularity of speech and manners, his championship of the poor, and his ostentatious disavowal of all selfish pretensions–partly by an artful mixture of stratagem and force. Solon, after having addressed fruitless remonstrances to Pisistratus himself, publicly denounced his designs in verses addressed to the people. The deception, whereby Pisistratus finally accomplished his design, is memorable in Grecian tradition. He appeared one day in the agora of Athens in his chariot with a pair of mules: he had intentionally wounded both his person and the mules, and in this condition he threw himself upon the compassion and defence of the people, pretending that his political enemies had violently attacked him. He implored the people to grant him a guard, and at the moment when their sympathies were freshly aroused both in his favor and against his supposed assassins, Aristo proposed formally to the ecclesia (the pro-bouleutic senate, being composed of friends of Pisistratus, had previously authorized the proposition) that a company of fifty club-men should be assigned as a permanent body-guard for the defence of Pisistratus. To this motion Solon opposed a strenuous resistance, but found himself overborne, and even treated as if he had lost his senses. The poor were earnest in favor of it, while the rich were afraid to express their dissent; and he could only comfort himself after the fatal vote had been passed, by exclaiming that he was wiser than the former and more determined than the latter. Such was one of the first known instances in which this memorable stratagem was played off against the liberty of a Grecian community.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.