The laws of Solon were inscribed on wooden rollers and triangular tablets . . . and preserved first in the Acropolis, subsequently in the Prytaneum.

Continuing Solon’s Early Greek Legislation,

our selection from History of Greece by George Grote published in 1846. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eighteen easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Solon’s Early Greek Legislation.

Time: 594 BC

Place: Athens

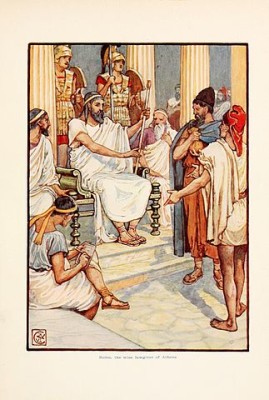

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The laws of Solon were inscribed on wooden rollers and triangular tablets, in the species of writing called “Boustrophedon” (lines alternating first from left to right, and next from right to left, like the course of the ploughman)–and preserved first in the Acropolis, subsequently in the Prytaneum. On the tablets, called “Cyrbis”, were chiefly commemorated the laws respecting sacred rites and sacrifices; on the pillars or rollers, of which there were at least sixteen, were placed the regulations respecting matters profane. So small are the fragments which have come down to us, and so much has been ascribed to Solon by the orators which belongs really to the subsequent times, that it is hardly possible to form any critical judgment respecting the legislation as a whole, or to discover by what general principles or purposes he was guided.

He left unchanged all the previous laws and practices respecting the crime of homicide, connected as they were intimately with the religious feelings of the people. The laws of Draco on this subject, therefore, remained, but on other subjects, according to Plutarch, they were altogether abrogated: there is, however, room for supposing that the repeal cannot have been so sweeping as this biographer represents.

The Solonian laws seem to have borne more or less upon all the great departments of human interest and duty. We find regulations political and religious, public and private, civil and criminal, commercial, agricultural, sumptuary, and disciplinarian. Solon provides punishment for crimes, restricts the profession and status of the citizen, prescribes detailed rules for marriage as well as for burial, for the common use of springs and wells, and for the mutual interest of conterminous farmers in planting or hedging their properties. As far as we can judge from the imperfect manner in which his laws come before us, there does not seem to have been any attempt at a systematic order or classification. Some of them are mere general and vague directions, while others again run into the extreme of specialty.

By far the most important of all was the amendment of the law of debtor and creditor which has already been adverted to, and the abolition of the power of fathers and brothers to sell their daughters and sisters into slavery. The prohibition of all contracts on the security of the body was itself sufficient to produce a vast improvement in the character and condition of the poorer population,–a result which seems to have been so sensibly obtained from the legislation of Solon, that Boeckh and some other eminent authors suppose him to have abolished villeinage and conferred upon the poor tenants a property in their lands, annulling the seigniorial rights of the landlord. But this opinion rests upon no positive evidence, nor are we warranted in ascribing to him any stronger measure in reference to the land than the annulment of the previous mortgages.

The first pillar of his laws contained a regulation respecting exportable produce. He forbade the exportation of all produce of the Attic soil, except olive oil alone. And the sanction employed to enforce observance of this law deserves notice, as an illustration of the ideas of the time: the archon was bound, on pain of forfeiting one hundred drachmas, to pronounce solemn curses against every offender. We are probably to take this prohibition in conjunction with other objects said to have been contemplated by Solon, especially the encouragement of artisans and manufacturers at Athens. Observing (we are told) that many new immigrants were just then flocking into Attica to seek an establishment, in consequence of its greater security, he was anxious to turn them rather to manufacturing industry than to the cultivation of a soil naturally poor. He forbade the granting of citizenship to any immigrants, except to such as had quitted irrevocably their former abodes and come to Athens for the purpose of carrying on some industrial profession; and in order to prevent idleness, he directed the senate of Areopagus to keep watch over the lives of the citizens generally, and punish every one who had no course of regular labor to support him. If a father had not taught his son some art or profession, Solon relieved the son from all obligation to maintain him in his old age. And it was to encourage the multiplication of these artisans that he insured, or sought to insure, to the residents in Attica, the exclusive right of buying and consuming all its landed produce except olive oil, which was raised in abundance, more than sufficient for their wants. It was his wish that the trade with foreigners should be carried on by exporting the produce of artisan labor, instead of the produce of land.

This commercial prohibition is founded on principles substantially similar to those which were acted upon in the early history of England, with reference both to corn and to wool, and in other European countries also. In so far as it was at all operative it tended to lessen the total quantity of produce raised upon the soil of Attica, and thus to keep the price of it from rising. But the law of Solon must have been altogether inoperative, in reference to the great articles of human subsistence; for Attica imported, both largely and constantly, grain and salt provisions, probably also wool and flax for the spinning and weaving of the women, and certainly timber for building. Whether the law was ever enforced with reference to figs and honey may well be doubted; at least these productions of Attica were in after times trafficked in, and generally consumed throughout Greece. Probably also in the time of Solon the silver mines of Laurium had hardly begun to be worked: these afterward became highly productive, and furnished to Athens a commodity for foreign payments no less convenient than lucrative.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.