The general tone of Grecian sentiment recognized no occupations as perfectly worthy of a free citizen except arms, agriculture, and athletic and musical exercises; and the proceedings of the Spartans, who kept aloof even from agriculture and left it to their helots, were admired, though they could not be copied . . .

Continuing Solon’s Early Greek Legislation,

our selection from History of Greece by George Grote published in 1846. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eighteen easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Solon’s Early Greek Legislation.

Time: 594 BC

Place: Athens

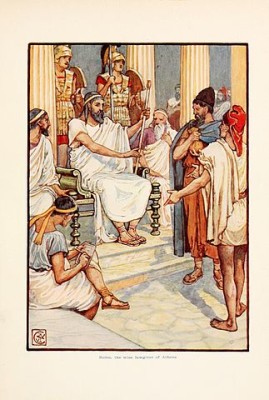

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

It is interesting to notice the anxiety, both of Solon and of Draco, to enforce among their fellow-citizens industrious and self-maintaining habits; and we shall find the same sentiment proclaimed by Pericles, at the time when Athenian power was at its maximum. Nor ought we to pass over this early manifestation in Attica of an opinion equitable and tolerant toward sedentary industry, which in most other parts of Greece was regarded as comparatively dishonorable. The general tone of Grecian sentiment recognized no occupations as perfectly worthy of a free citizen except arms, agriculture, and athletic and musical exercises; and the proceedings of the Spartans, who kept aloof even from agriculture and left it to their helots, were admired, though they could not be copied, throughout most of the Hellenic world. Even minds like Plato, Aristotle, and Xenophon concurred to a considerable extent in this feeling, which they justified on the ground that the sedentary life and unceasing house-work of the artisan were inconsistent with military aptitude. The town-occupations are usually described by a word which carries with it contemptuous ideas, and though recognized as indispensable to the existence of the city, are held suitable only for an inferior and semi-privileged order of citizens. This, the received sentiment among Greeks, as well as foreigners, found a strong and growing opposition at Athens, as I have already said–corroborated also by a similar feeling at Corinth. The trade of Corinth, as well as of Chalcis in Euboea, was extensive, at a time when that of Athens had scarce any existence. But while the despotism of Periander can hardly have failed to operate as a discouragement to industry at Corinth, the contemporaneous legislation of Solon provided for traders and artisans a new home at Athens, giving the first encouragement to that numerous town-population both in the city and in the Piræus, which we find actually residing there in the succeeding century. The multiplication of such town residents, both citizens and “metics” (“i.e.,” resident persons, not citizens, but enjoying an assured position and civil rights), was a capital fact in the onward march of Athens, since it determined not merely the extension of her trade, but also the preeminence of her naval forces–and thus, as a further consequence, lent extraordinary vigor to her democratic government. It seems, moreover, to have been a departure from the primitive temper of Atticism, which tended both to cantonal residence and rural occupation. We have, therefore, the greater interest in noting the first mention of it as a consequence of the Solonian legislation.

To Solon is first owing the admission of a power of testamentary bequest at Athens in all cases in which a man had no legitimate children. According to the preexisting custom, we may rather presume that if a deceased person left neither children nor blood relations, his property descended (as at Rome) to his gens and phratry. Throughout most rude states of society the power of willing is unknown, as among the ancient Germans–among the Romans prior to the twelve tables–in the old laws of the Hindus, etc. Society limits a man’s interest or power of enjoyment to his life, and considers his relatives as having joint reversionary claims to his property, which take effect, in certain determinate proportions, after his death. Such a law was the more likely to prevail at Athens, since the perpetuity of the family sacred rites, in which the children and near relatives partook of right, was considered by the Athenians as a matter of public as well as of private concern. Solon gave permission to every man dying without children to bequeath his property by will as he should think fit; and the testament was maintained unless it could be shown to have been procured by some compulsion or improper seduction. Speaking generally, this continued to be the law throughout the historical times of Athens. Sons, wherever there were sons, succeeded to the property of their father in equal shares, with the obligation of giving out their sisters in marriage along with a certain dowry. If there were no sons, then the daughters succeeded, though the father might by will, within certain limits, determine the person to whom they should be married, with their rights of succession attached to them; or might, with the consent of his daughters, make by will certain other arrangements about his property. A person who had no children or direct lineal descendants might bequeath his property at pleasure: if he died without a will, first his father, then his brother or brother’s children, next his sister or sister’s children succeeded: if none such existed, then the cousins by the father’s side, next the cousins by the mother’s side,–the male line of descent having preference over the female.

Such was the principle of the Solonian laws of succession, though the particulars are in several ways obscure and doubtful. Solon, it appears, was the first who gave power of superseding by testament the rights of agnates and gentiles to succession,–a proceeding in consonance with his plan of encouraging both industrious occupation and the consequent multiplication of individual acquisitions.

It has been already mentioned that Solon forbade the sale of daughters or sisters into slavery by fathers or brothers; a prohibition which shows how much females had before been looked upon as articles of property. And it would seem that before his time the violation of a free woman must have been punished at the discretion of the magistrates; for we are told that he was the first who enacted a penalty of one hundred drachmas against the offender, and twenty drachmas against the seducer of a free woman. Moreover, it is said that he forbade a bride when given in marriage to carry with her any personal ornaments and appurtenances, except to the extent of three robes and certain matters of furniture not very valuable.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.