Among the various laws of Solon, there are few which have attracted more notice than that which pronounces the man who in a sedition stood aloof, and took part with neither side, to be dishonored and disfranchised.

Continuing Solon’s Early Greek Legislation,

our selection from History of Greece by George Grote published in 1846. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eighteen easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Solon’s Early Greek Legislation.

Time: 594 BC

Place: Athens

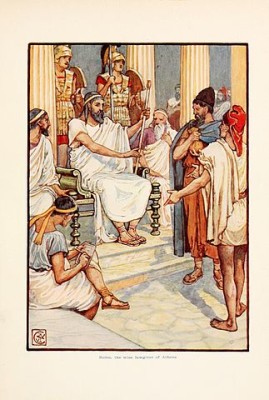

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Solon further imposed upon women several restraints in regard to proceeding at the obsequies of deceased relatives. He forbade profuse demonstrations of sorrow, singing of composed dirges, and costly sacrifices and contributions. He limited strictly the quantity of meat and drink admissible for the funeral banquet, and prohibited nocturnal exit, except in a car and with a light. It appears that both in Greece and Rome, the feelings of duty and affection on the part of surviving relatives prompted them to ruinous expense in a funeral, as well as to unmeasured effusions both of grief and conviviality; and the general necessity experienced for legal restriction is attested by the remark of Plutarch, that similar prohibitions to those enacted by Solon were likewise in force at his native town of Chæronea.

Other penal enactments of Solon are yet to be mentioned. He forbade absolutely evil speaking with respect to the dead. He forbade it likewise with respect to the living, either in a temple or before judges or archons, or at any public festival–on pain of a forfeit of three drachmas to the person aggrieved, and two more to the public treasury. How mild the general character of his punishments was, may be judged by this law against foul language, not less than by the law before mentioned against rape. Both the one and the other of these offences were much more severely dealt with under the subsequent law of democratical Athens. The peremptory edict against speaking ill of a deceased person, though doubtless springing in a great degree from disinterested repugnance, is traceable also in part to that fear of the wrath of the departed which strongly possessed the early Greek mind.

It seems generally that Solon determined by law the outlay for the public sacrifices, though we do not know what were his particular directions. We are told that he reckoned a sheep and a medimnus (of wheat or barley?) as equivalent, either of them, to a drachma, and that he also prescribed the prices to be paid for first-rate oxen intended for solemn occasions. But it astonishes us to see the large recompense which he awarded out of the public treasury to a victor at the Olympic or Isthmian games: to the former, five hundred drachmas, equal to one year’s income of the highest of the four classes on the census; to the latter one hundred drachmas. The magnitude of these rewards strikes us the more when we compare them with the fines on rape and evil speaking. We cannot be surprised that the philosopher Xenophanes noticed, with some degree of severity, the extravagant estimate of this species of excellence, current among the Grecian cities. At the same time, we must remember both that these Pan-Hellenic games presented the chief visible evidence of peace and sympathy among the numerous communities of Greece, and that in the time of Solon, factitious reward was still needful to encourage them. In respect to land and agriculture Solon proclaimed a public reward of five drachmas for every wolf brought in, and one drachma for every wolf’s cub; the extent of wild land has at all times been considerable in Attica. He also provided rules respecting the use of wells between neighbors, and respecting the planting in conterminous olive grounds. Whether any of these regulations continued in operation during the better-known period of Athenian history cannot be safely affirmed.

In respect to theft, we find it stated that Solon repealed the punishment of death which Draco had annexed to that crime, and enacted, as a penalty, compensation to an amount double the value of the property stolen. The simplicity of this law perhaps affords ground for presuming that it really does belong to Solon. But the law which prevailed during the time of the orators respecting theft must have been introduced at some later period, since it enters into distinctions and mentions both places and forms of procedure, which we cannot reasonably refer to the forty-sixth Olympiad. The public dinners at the Prytaneum, of which the archons and a select few partook in common, were also either first established, or perhaps only more strictly regulated, by Solon. He ordered barley cakes for their ordinary meals, and wheaten loaves for festival days, prescribing how often each person should dine at the table. The honor of dining at the table of the Prytaneum was maintained throughout as a valuable reward at the disposal of the government.

Among the various laws of Solon, there are few which have attracted more notice than that which pronounces the man who in a sedition stood aloof, and took part with neither side, to be dishonored and disfranchised. Strictly speaking, this seems more in the nature of an emphatic moral denunciation, or a religious curse, than a legal sanction capable of being formally applied in an individual case and after judicial trial,–though the sentence of “atimy”, under the more elaborated Attic procedure, was both definite in its penal consequences and also judicially delivered. We may, however, follow the course of ideas under which Solon was induced to write this sentence on his tables, and we may trace the influence of similar ideas in later Attic institutions. It is obvious that his denunciation is confined to that special case in which a sedition has already broken out: we must suppose that Cylon has seized the Acropolis, or that Pisistratus, Megacles, and Lycurgus are in arms at the head of their partisans. Assuming these leaders to be wealthy and powerful men, which would in all probability be the fact, the constituted authority–such as Solon saw before him in Attica, even after his own organic amendments–was not strong enough to maintain the peace; it became, in fact, itself one of the contending parties. Under such given circumstances, the sooner every citizen publicly declared his adherence to some of them, the earlier this suspension of legal authority was likely to terminate. Nothing was so mischievous as the indifference of the mass, or their disposition to let the combatants fight out the matter among themselves, and then to submit to the victor.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.