Athen’s democracy progressed much after Solon. We shall see that the democracy of the ensuing century fulfilled the conditions of order, as well as of progress, better than the Solonian constitution.

Continuing Solon’s Early Greek Legislation,

our selection from History of Greece by George Grote published in 1846. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eighteen easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Solon’s Early Greek Legislation.

Time: 594 BC

Place: Athens

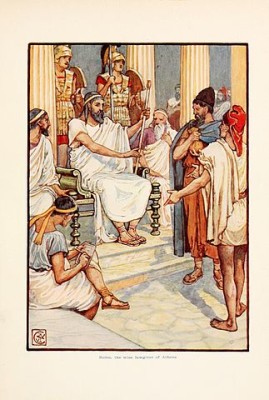

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

It is, in my judgment, a mistake to suppose that Solon transferred the judicial power of the archons to a popular dicastery. These magistrates still continued self-acting judges, deciding and condemning without appeal–not mere presidents of an assembled jury, as they afterward came to be during the next century. For the general exercise of such power they were accountable after their year of office. Such accountability was the security against abuse–a very insufficient security, yet not wholly inoperative. It will be seen, however, presently that these archons, though strong to coerce, and perhaps to oppress, small and poor men, had no means of keeping down rebellious nobles of their own rank, such as Pisistratus, Lycurgus, and Megacles, each with his armed followers. When we compare the drawn swords of these ambitious competitors, ending in the despotism of one of them, with the vehement parliamentary strife between Themistocles and Aristides afterward, peaceably decided by the vote of the sovereign people and never disturbing the public tranquillity–we shall see that the democracy of the ensuing century fulfilled the conditions of order, as well as of progress, better than the Solonian constitution.

To distinguish this Solonian constitution from the democracy which followed it, is essential to a due comprehension of the progress of the Greek mind, and especially of Athenian affairs. That democracy was achieved by gradual steps. Demosthenes and Æschines lived under it as a system consummated and in full activity, when the stages of its previous growth were no longer matter of exact memory; and the dicasts then assembled in judgment were pleased to hear their constitution associated with the names either of Solon or of Theseus. Their inquisitive contemporary Aristotle was not thus misled: but even commonplace Athenians of the century preceding would have escaped the same delusion. For during the whole course of the democratical movement, from the Persian invasion down to the Peloponnesian war, and especially during the changes proposed by Pericles and Ephialtes, there was always a strenuous party of resistance, who would not suffer the people to forget that they had already forsaken, and were on the point of forsaking still more, the orbit marked out by Solon. The illustrious Pericles underwent innumerable attacks both from the orators in the assembly and from the comic writers in the theatre. And among these sarcasms on the political tendencies of the day we are probably to number the complaint, breathed by the poet Cratinus, of the desuetude into which both Solon and Draco had fallen–“I swear (said he in a fragment of one of his comedies) by Solon and Draco, whose wooden tablets (of laws) are now employed by people to roast their barley.” The laws of Solon respecting penal offences, respecting inheritance and adoption, respecting the private relations generally, etc., remained for the most part in force: his quadripartite census also continued, at least for financial purposes, until the archonship of Nausinicus in B.C. 377–so that Cicero and others might be warranted in affirming that his laws still prevailed at Athens: but his political and judicial arrangements had undergone a revolution not less complete and memorable than the character and spirit of the Athenian people generally. The choice, by way of lot, of archons and other magistrates–and the distribution by lot of the general body of dicasts or jurors into panels for judicial business–may be decidedly considered as not belonging to Solon, but adopted after the revolution of Clisthenes; probably the choice of senators by lot also. The lot was a symptom of pronounced democratical spirit, such as we must not seek in the Solonian institutions.

It is not easy to make out distinctly what was the political position of the ancient gentes and phratries, as Solon left them. The four tribes consisted altogether of gentes and phratries, insomuch that no one could be included in any one of the tribes who was not also a member of some gens and phratry. Now the new pro-bouleutic, or pre-considering, senate consisted of four hundred members,–one hundred from each of the tribes: persons not included in any gens or phratry could therefore have had no access to it. The conditions of eligibility were similar, according to ancient custom, for the nine archons–of course, also, for the senate of Areopagus. So that there remained only the public assembly, in which an Athenian not a member of these tribes could take part: yet he was a citizen, since he could give his vote for archons and senators, and could take part in the annual decision of their accountability, besides being entitled to claim redress for wrong from the archons in his own person–while the alien could only do so through the intervention of an avouching citizen or Prostates. It seems, therefore, that all persons not included in the four tribes, whatever their grade of fortune might be, were on the same level in respect to political privilege as the fourth and poorest class of the Solonian census. It has already been remarked, that even before the time of Solon the number of Athenians not included in the gentes or phratries was probably considerable: it tended to become greater and greater, since these bodies were close and unexpansive, while the policy of the new lawgiver tended to invite industrious settlers from other parts of Greece and Athens. Such great and increasing inequality of political privilege helps to explain the weakness of the government in repelling the aggressions of Pisistratus, and exhibits the importance of the revolution afterward wrought by Clisthenes, when he abolished (for all political purposes) the four old tribes, and created ten new comprehensive tribes in place of them.

In regard to the regulations of the senate and the assembly of the people, as constituted by Solon, we are altogether without information: nor is it safe to transfer to the Solonian constitution the information, comparatively ample, which we possess respecting these bodies under the later democracy.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.