Aristotle tells us that Solon bestowed upon the people as much power as was indispensable, but no more: the power to elect their magistrates and hold them to accountability. . . But Solon’s constitution, though only the foundation, was yet the indispensable foundation, of the subsequent democracy.

Continuing Solon’s Early Greek Legislation,

our selection from History of Greece by George Grote published in 1846. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eighteen easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Solon’s Early Greek Legislation.

Time: 594 BC

Place: Athens

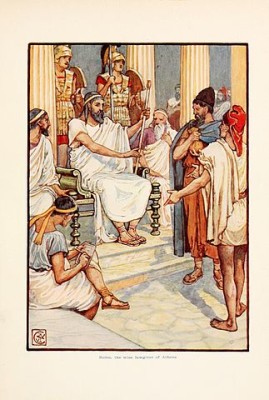

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

If we examine the facts of the case, we shall see that nothing more than the bare foundation of the democracy of Athens as it stood in the time of Pericles can reasonably be ascribed to Solon. “I gave to the people (Solon says in one of his short remaining fragments) as much strength as sufficed for their needs, without either enlarging or diminishing their dignity: for those too, who possessed power and were noted for wealth, I took care that no unworthy treatment should be reserved. I stood with the strong shield cast over both parties so as not to allow an unjust triumph to either.” Again, Aristotle tells us that Solon bestowed upon the people as much power as was indispensable, but no more: the power to elect their magistrates and hold them to accountability: if the people had had less than this, they could not have been expected to remain tranquil–they would have been in slavery and hostile to the constitution. Not less distinctly does Herodotus speak, when he describes the revolution subsequently operated by Clisthenes–the latter (he tells us) found “the Athenian people excluded from everything.” These passages seem positively to contradict the supposition, in itself sufficiently improbable, that Solon is the author of the peculiar democratic institutions of Athens, such as the constant and numerous dicasts for judicial trials and revision of laws. The genuine and forward democratic movement of Athens begins only with Clisthenes, from the moment when that distinguished Alcmaeonid, either spontaneously, or from finding himself worsted in his party strife with Isagoras, purchased by large popular concessions the hearty cooperation of the multitude under very dangerous circumstances. While Solon, in his own statement as well as in that of Aristotle, gave to the people as much power as was strictly needful–but no more–Clisthenes (to use the significant phrase of Herodotus), “being vanquished in the party contest with his rival, “took the people into partnership”.” It was, thus, to the interests of the weaker section, in a strife of contending nobles, that the Athenian people owed their first admission to political ascendancy–in part, at least, to this cause, though the proceedings of Clisthenes indicate a hearty and spontaneous popular sentiment. But such constitutional admission of the people would not have been so astonishingly fruitful in positive results, if the course of public events for the half century after Clisthenes had not been such as to stimulate most powerfully their energy, their self-reliance, their mutual sympathies, and their ambition. I shall recount in a future chapter these historical causes, which, acting upon the Athenian character, gave such efficiency and expansion to the great democratic impulse communicated by Clisthenes: at present it is enough to remark that that impulse commences properly with Clisthenes, and not with Solon.

But the Solonian constitution, though only the foundation, was yet the indispensable foundation, of the subsequent democracy. And if the discontents of the miserable Athenian population, instead of experiencing his disinterested and healing management, had fallen at once into the hands of selfish power-seekers like Cylon or Pisistratus–the memorable expansion of the Athenian mind during the ensuing century would never have taken place, and the whole subsequent history of Greece would probably have taken a different course. Solon left the essential powers of the state still in the hands of the oligarchy. The party combats between Pisistratus, Lycurgus, and Megacles, thirty years after his legislation, which ended in the despotism of Pisistratus, will appear to be of the same purely oligarchical character as they had been before Solon was appointed archon. But the oligarchy which he established was very different from the unmitigated oligarchy which he found, so teeming with oppression and so destitute of redress, as his own poems testify.

It was he who first gave both to the citizens of middling property and to the general mass a “locus standi” against the Eupatrids. He enabled the people partially to protect themselves, and familiarized them with the idea of protecting themselves, by the peaceful exercise of a constitutional franchise. The new force, through which this protection was carried into effect, was the public assembly called “Heliæa”, regularized and armed with enlarged prerogatives and further strengthened by its indispensable ally–the pro-bouleutic, or pre-considering, senate. Under the Solonian constitution, this force was merely secondary and defensive, but after the renovation of Clisthenes it became paramount and sovereign. It branched out gradually into those numerous popular dicasteries which so powerfully modified both public and private Athenian life, drew to itself the undivided reverence and submission of the people, and by degrees rendered the single magistracies essentially subordinate functions. The popular assembly, as constituted by Solon, appearing in modified efficiency and trained to the office of reviewing and judging the general conduct of a past magistrate–forms the intermediate stage between the passive Homeric agora and those omnipotent assemblies and dicasteries which listened to Pericles or Demosthenes. Compared with these last, it has in it but a faint streak of democracy–and so it naturally appeared to Aristotle, who wrote with a practical experience of Athens in the time of the orators; but compared with the first, or with the ante-Solonian constitution of Attica, it must doubtless have appeared a concession eminently democratical. To impose upon the Eupatrid archon the necessity of being elected, or put upon his trial of after-accountability, by the “rabble” of freemen (such would be the phrase in Eupatrid society), would be a bitter humiliation to those among whom it was first introduced; for we must recollect that this was the most extensive scheme of constitutional reform yet propounded in Greece, and that despots and oligarchies shared between them at that time the whole Grecian world. As it appears that Solon, while constituting the popular assembly with its pro-bouleutic senate, had no jealousy of the senate of Areopagus, and indeed, even enlarged its powers, we may infer that his grand object was, not to weaken the oligarchy generally, but to improve the administration and to repress the misconduct and irregularities of the individual archons; and that, too, not by diminishing their powers, but by making some degree of popularity the condition both of their entry into office, and of their safety or honor after it.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Like!! I blog frequently and I really thank you for your content. The article has truly peaked my interest.